New research reveals the genetic material that codes for bat adaptations and “superpowers.”

Those bat powers include the ability to fly, to use sound to move effortlessly in complete darkness, to tolerate and survive potentially deadly viruses, and to resist aging and cancer.

The project, called Bat1K, sequenced the genome of six widely divergent living bat species.

Although other bat genomes have been published before, the Bat1K genomes are 10 times more complete than any bat genome published to date.

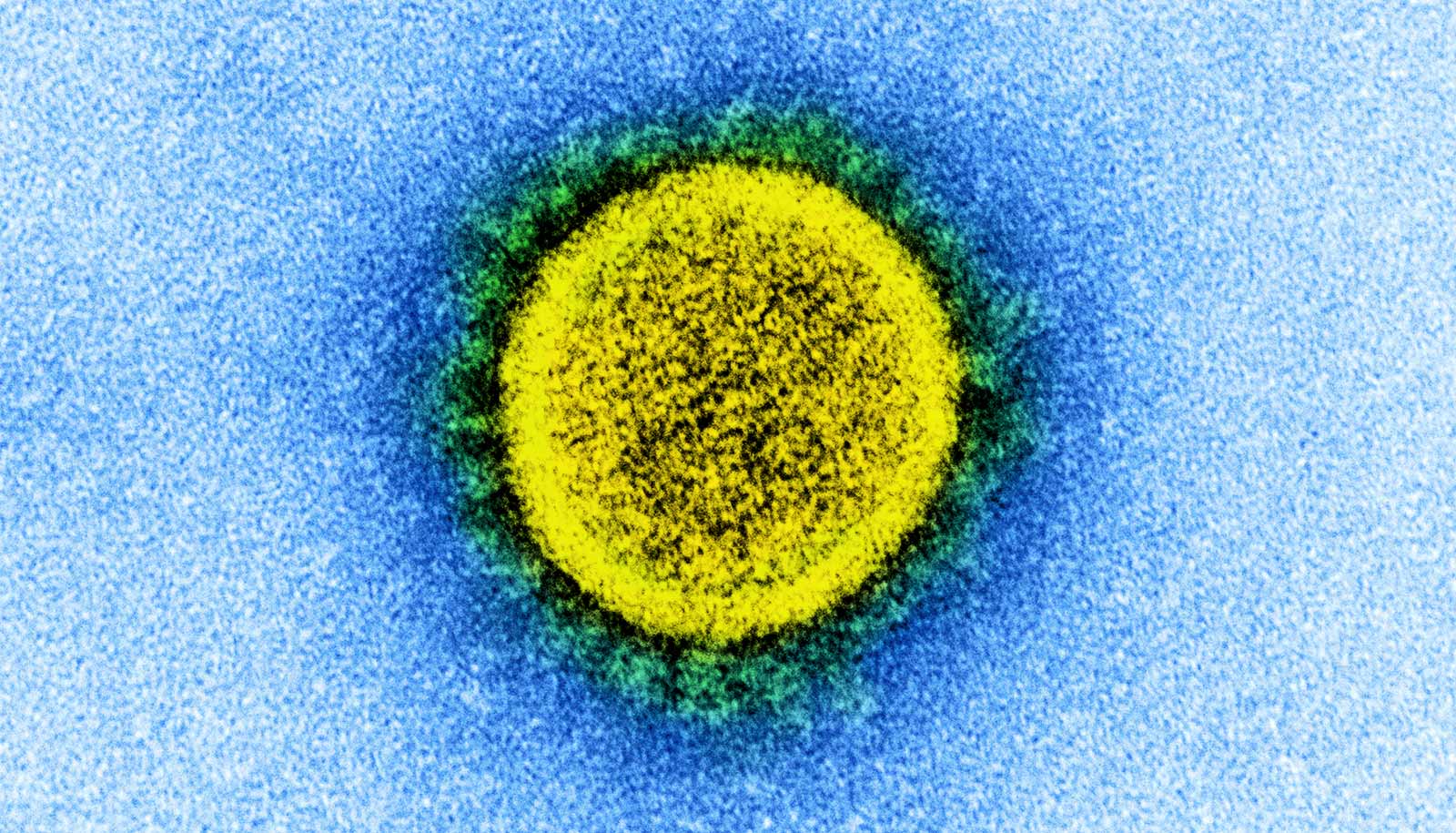

One aspect of the paper findings shows evolution through gene expansion and loss in a family of genes, APOBEC3, which is known to play an important role in immunity to viruses in other mammals. The details in the paper that explain this evolution set the groundwork for investigating how these genetic changes, found in bats but not in other mammals, could help prevent the worst outcomes of viral diseases in other mammals, including humans.

“More and more, we find gene duplications and losses as important processes in the evolution of new features and functions across the Tree of Life,” says Liliana M. Dávalos, an evolutionary biologist and professor in the department of ecology and evolution at Stony Brook University and coauthor of the paper in Nature.

“But, determining when genes have duplicated is difficult if the genome is incomplete, and it is even harder to figure out if genes have been lost. At extremely high quality, the new bat genomes leave no doubts about changes in important gene families that could not be discovered otherwise with lower-quality genomes.”

To generate the bat genomes, the team used the newest technologies of the DRESDEN-concept Genome Center, a shared technology resource in Dresden, Germany to sequence the bat’s DNA, and generated new methods to assemble these pieces into the correct order and to identify the genes present. While previous efforts had identified genes with the potential to influence the unique biology of bats, uncovering how gene duplications contributed to this unique biology was complicated by incomplete genomes.

The team compared these bat genomes against 42 other mammals to address the unresolved question of where bats are located within the mammalian tree of life. Using novel phylogenetic methods and comprehensive molecular data sets, the team found the strongest support for bats being most closely related to a group called Fereuungulata that consists of carnivorans (which includes dogs, cats, and seals, among other species), pangolins, whales, and ungulates (hooved mammals).

To uncover genomic changes that contribute to the unique adaptations found in bats, the team systematically searched for gene differences between bats and other mammals, identifying regions of the genome that have evolved differently in bats and the loss and gain of genes that may drive bats’ unique traits.

“It is thanks to a series of sophisticated statistical analyses that we have started to uncover the genetics behind bats’ ‘superpowers,’ including their strong apparent abilities to tolerate and overcome RNA viruses,” says Dávalos.

The researchers found evidence the exquisite genomes revealed “fossilized viruses,” evidence of surviving past viral infections, and showed that bat genomes contained a higher diversity of these viral remnants than other species providing a genomic record of ancient historical interaction with viral infections. The genomes also revealed the signatures of many other genetic elements besides ancient viral insertions, including ‘jumping genes’ or transposable elements.

Funding for the study came in part from the Max Planck Society, the European Research Council, the Irish Research Council, the Human Frontiers of Science Program, and the National Science Foundation.

Source: Stony Brook University