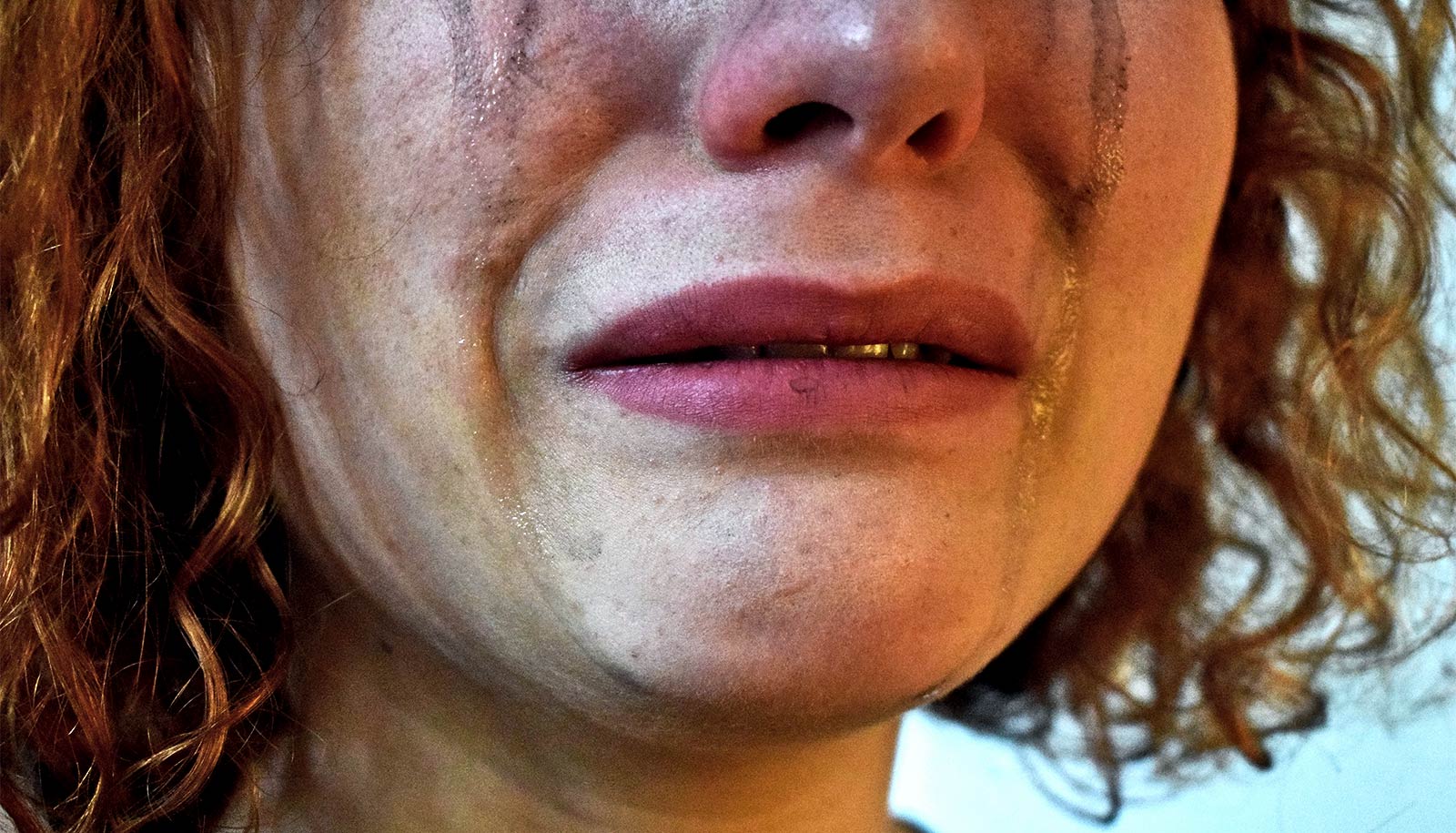

Every death from COVID-19 will affect approximately nine surviving family members, according to a new study of kinship networks in the United States.

Deaths from COVID-19 will have a ripple effect causing impacts on the mental health and health of surviving family members. But the extent of that impact has been hard to assess until now.

For example, if the virus kills 190,000 people, 1.7 million will experience the loss of a close relative, says Ashton Verdery, associate professor of sociology, demography and social data analytics, and an affiliate of the Population Research Institute and Institute for Computational and Data Sciences at Penn State.

A kinship network includes grandparents, parents, siblings, spouses, and children.

According to Verdery, the multiplier could serve as an indicator to help raise awareness about the scale of the disease and the ripple effects that the disease may have on a community, as well as prepare officials and business leaders to manage those effects.

“It’s very helpful to have a sense of the potential impacts that the pandemic could have,” says Verdery. “And, for employers, it calls attention to policies around family leave and paid leave. At the federal level, it might inform officials about possible extensions for FMLA (Family and Medical Leave Act). There could also be some implications for caretaking. For example, a lot of children grow up in grandparent-led houses and they would be impacted.”

The researchers say some slight differences in the bereavement multiplier exist between white and Black Americans. For white Americans, the median multiplier is estimated at 8.86, while it is 9.18 for Black Americans, says Verdery.

The researchers also suggest that people may be facing the loss of a close loved one at a younger age because of the virus, according to Verdery.

“There are a substantial number of people who may be losing parents that we would consider younger adults and a substantial number of people may be losing spouses who are in their 50s or 60s,” he says.

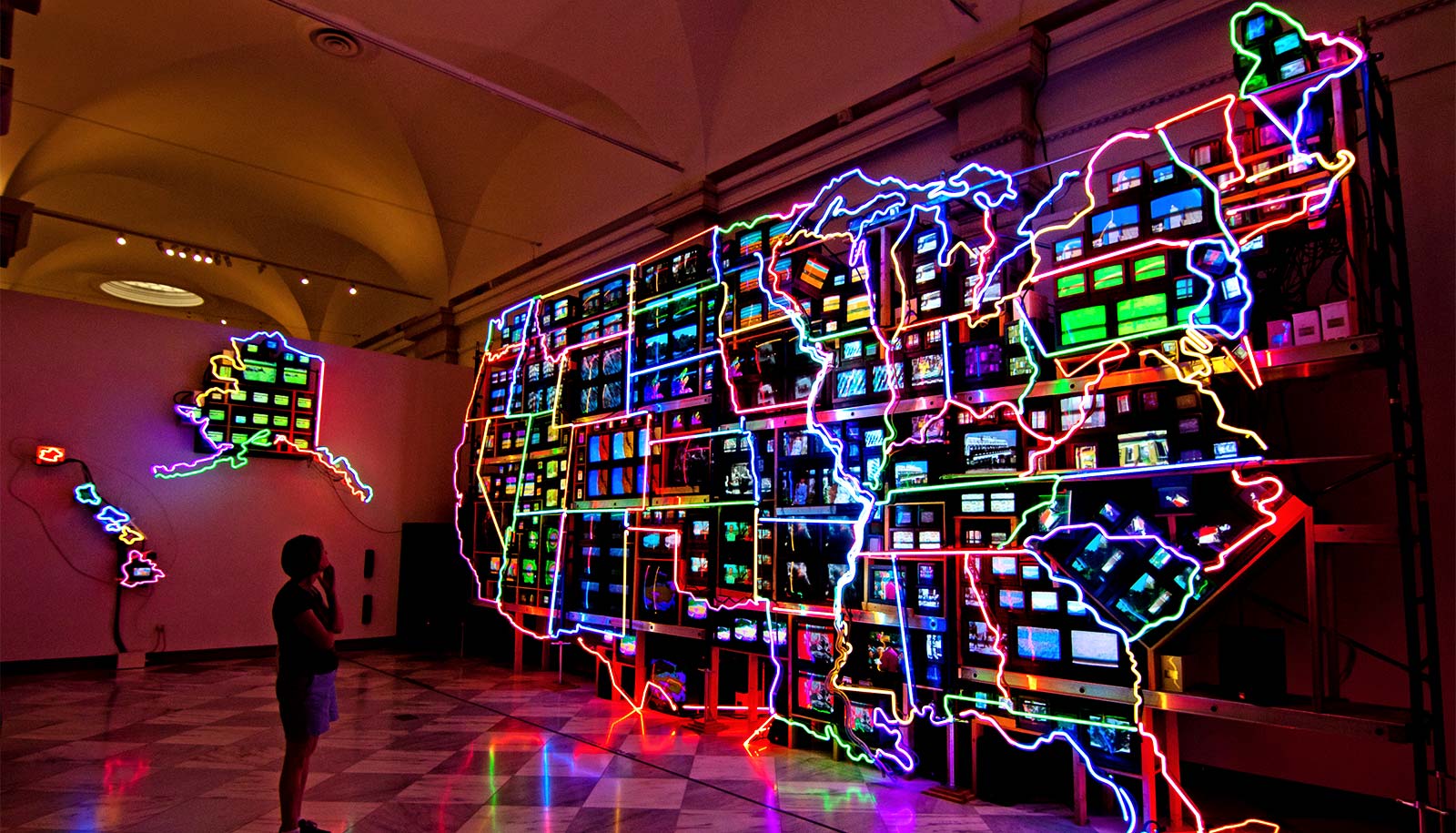

While there are some limitations, the indicator could help local officials understand the waves of grief that may affect specific areas and regions of the country.

“Our statistics are based on national averages, so it might not translate perfectly, but you could imagine that this could serve as a baseline level to go forward to understand the differences between areas where the outbreaks are severe and places where the outbreaks may not be so severe,” says Verdery. “There are regional differences in some of these kinship statistics that would make it less than perfect, but it would be a reasonable first approximation.”

For this study, the team built on previous investigations that happened soon after the virus began to spread worldwide.

“The big challenge with the former work was that we used a certain percentage of infections and a certain percentage of deaths,” says Verdery.

“In that model, there is an inherent prediction that if so many people are infected, there would be a certain number of people who would die and, then, the model estimated how many people will be affected by those deaths. But, thinking through this, we wanted to create a statistic that is easy to understand and one that doesn’t rely on specific predictions about death counts.”

The researchers undertook a computational analysis of COVID-19 mortality in kinship networks of white and Black Americans. The demographic data was drawn from the historical record or recent Census Bureau national projections to create a complete kinship network, from which the researchers analyzed grandparents, parents, siblings, spouses, and children.

In the future, the researchers plan to investigate how the bereavement factor during other mortality spikes, such as the opioid epidemic, changes over time and how to better understand when that factor becomes broadly felt across the community.

The research appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Coauthors are from the University of Southern California, the University of Western Ontario, and Penn State.

Support for the work came from the National Institute on Aging, the Penn State Population Research Institute, the University of Southern California Center for the Changing Family, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation.

Source: Penn State