Bird poop may pose more health risks than people realize, according to environmental engineers who study antibiotic resistance.

Their study found high levels of genes that encode antibiotic resistance harbored by opportunistic pathogens in the droppings of common urban ducks, crows, and gulls.

Previous studies determined bird-carried antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) and bacteria (ARBs) can transfer to humans through swimming, contact with feces or affected soil, or inhalation of aerosolized fecal particles. Studies have also analyzed bird feces found near ARG hotspots like wastewater treatment plants and drainage from poultry farms.

The new study digs deeper to quantify the abundance, diversity, and seasonal persistence of ARGs.

“We still do not fully understand what factors exert selective pressure for the occurrence of ARGs in the gastrointestinal system of wild urban birds,” says coauthor Pedro Alvarez, civil and environmental engineer at Rice University’s Brown School of Engineering.

“Residual antibiotics that are incidentally assimilated during foraging is likely one of these factors, but further research is needed to discern the importance of other potential etiological factors, such as bird diet, age, gut microbiome structure, and other stressors.”

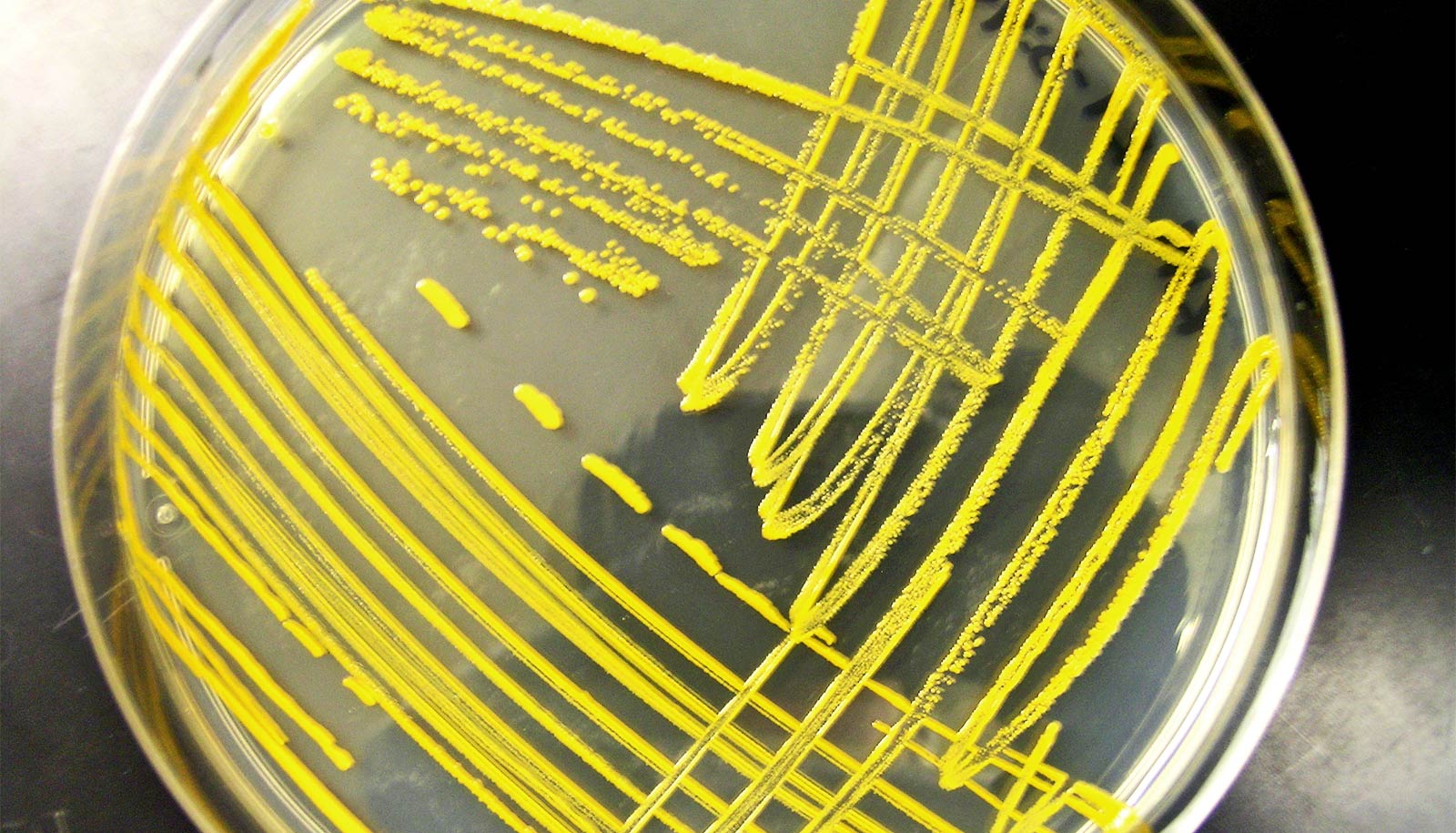

The team compared “freshly deposited” samples from each species found around Houston during the winter and summer months to samples from poultry and livestock known to carry some of the same mutations.

They found that ARGs in all of the species, regardless of season, encoded significant resistance to tetracycline, beta-lactam, and sulfonamide antibiotics. The researchers were surprised to see the relatively high abundance of ARGs were comparable to those found in the fresh feces of poultry occasionally fed with antibiotics.

They also found intI1, an integron that facilitates rapid bacterial acquisition of antibiotic resistance, was five times more abundant in the birds than in farm animals.

“Our results indicate that urban wild birds are an overlooked but potentially important reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes, although their significance as vectors for direct transmission of resistant infections is possible but improbable due to low frequency of human contact,” Alvarez says.

The team also looked for ARGs in soil up to 1 inch deep around bird deposits and discovered they are “moderately persistent” in the environment, with half-lives of up to 11.1 days.

Of the three species, crows showed a significantly lower level of ARGs during the summer compared to ducks and gulls, they report.

“That’s probably due to differences in their ecological niches, foraging patterns, and gut microbiome,” says coauthor and graduate student graduate student Ruonan Sun.

“Crows are omnivores and feed on abundant natural food with less anthropogenic contaminations in the summer. In addition, the composition of their gut microbiome impacts ARG dissemination and enrichment in vivo, and therefore influences ARG levels in the excreted bird feces.”

The researchers found that opportunistic pathogens including bacteria that cause urinary tract infections, sepsis, and respiratory infections were common in the feces of all of the birds, and another associated with food poisoning was detected in samples collected during the winter.

Winter feces, they write, contained more of the bad bacteria that may also harbor ARGs, possibly due to lower sunlight inactivation and differences in moisture levels and temperature.

“Our study raises awareness to avoid direct contact with bird droppings in urban public areas, especially for vulnerable or sensitive populations,” says study leader and postdoctoral research associate Pingfeng Yu. “Meanwhile, regular cleaning should also help to mitigate associated health risks.”

The National Science Foundation and the China Scholarship Council supported the research, which appears in the journal Environmental Pollution.

Source: Rice University