Humans and monkeys may not speak the same lingo, but our ways of thinking are a lot more similar than previously thought, according to a new study.

In experiments on 100 study participants across age groups, cultures, and species, researchers found that Indigenous Tsimane’ people in Bolivia’s Amazon rainforest, American adults and preschoolers, and macaque monkeys all show, to varying degrees, a knack for “recursion,” a cognitive process of arranging words, phrases, or symbols in a way that helps convey complex commands, sentiments, and ideas.

“…this ability may not be as unique to humans as is commonly thought.”

The findings in Science Advances shed new light on our understanding of the evolution of language, the researchers say.

“For the first time, we have strong empirical evidence about patterns of thinking that come naturally to probably all humans and, to a lesser extent, non-human primates,” says coauthor Steven Piantadosi, a assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Indeed, the researchers found the monkeys performed far better in the tests than the researchers had predicted.

“Our data suggest that, with sufficient training, monkeys can learn to represent a recursive process, meaning that this ability may not be as unique to humans as is commonly thought,” says coauthor Sam Cheyette, a PhD student in Piantadosi’s lab.

Known in linguistics as “nested structures,” recursive phrases within phrases are crucial to syntax and semantics in human language. A simple example is a British nursery rhyme that talks about “the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.”

The study was led by Harvard postdoctoral researcher Stephen Ferrigno, who traveled to Bolivia’s Amazon rainforest where Tsimane’ people practice subsistence farming, and live a traditional lifestyle with relatively little schooling and modern technology.

Ferrigno and fellow researchers sought to analyze what it is about human thinking that sets human and non-human primates apart. While numerous functions are unique to the human brain, we share neural similarities with monkeys, and these latest findings confirm that connection.

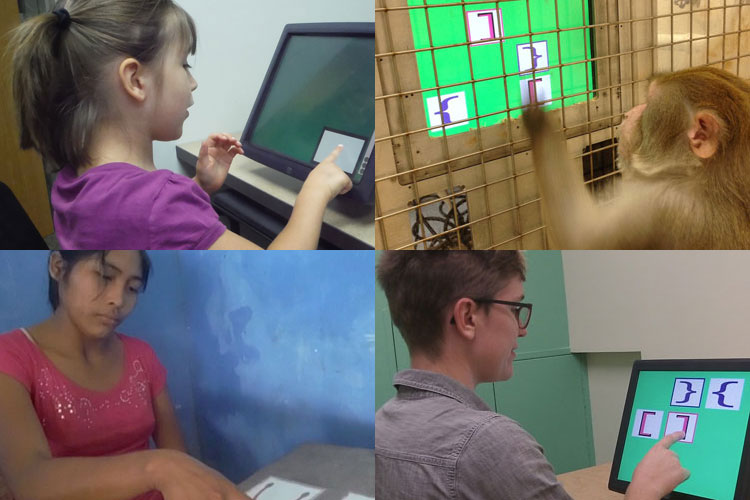

Researchers tested the recursive skills of 10 US adults, 50 preschoolers and kindergarteners, 37 members of the Tsimane’, and three male macaque monkeys.

First, all participants were trained to memorize different sequences of symbols in a particular order. Specifically, they learned sequences such as { ( ) } or { [ ] }, which are analogous to some linguistic nested structures.

Participants from the US and monkeys used a large touchscreen monitor to memorize the sequences. They heard a ding if they got a symbol in the right place, a buzzer if they got it wrong and a chime if the whole sequence was correct. The monkeys received snacks or juice as positive feedback.

Meanwhile, researchers tested the Tsimane’ participants, who are less accustomed to interacting with computers, with paper index cards and gave them verbal feedback.

Next, all participants were asked to place, in the right order, four images from different groupings shown in random order on the screen.

To varying degrees, the participants all arranged their new lists in recursive structures, which is remarkable given that “Tsimane’ adults, preschool children, and monkeys, who lack formal mathematics and reading training, had never been exposed to such stimuli before testing,” the study notes.

“These results are convergent with recent findings that monkeys can learn other kinds of structures found in human grammar,” Piantadosi says.

Additional researchers from UC Berkeley, Harvard University, and Carnegie Mellon University contributed to the study.

Source: UC Berkeley