Miniature electronics based on the Japanese art of kirigami are ideal for pressure sensing, researchers report.

Miniature devices, notably those that bulge out from 2D surfaces like pop-up greeting cards, have seamlessly found their way into pressure-sensing and energy-harvesting technologies because it’s possible to frequently stretch, compress, or twist them.

Despite their force-bearing abilities, it is still unclear if repeated physical stress can damage the working of these miniature devices, particularly if there is already a defect in their construction.

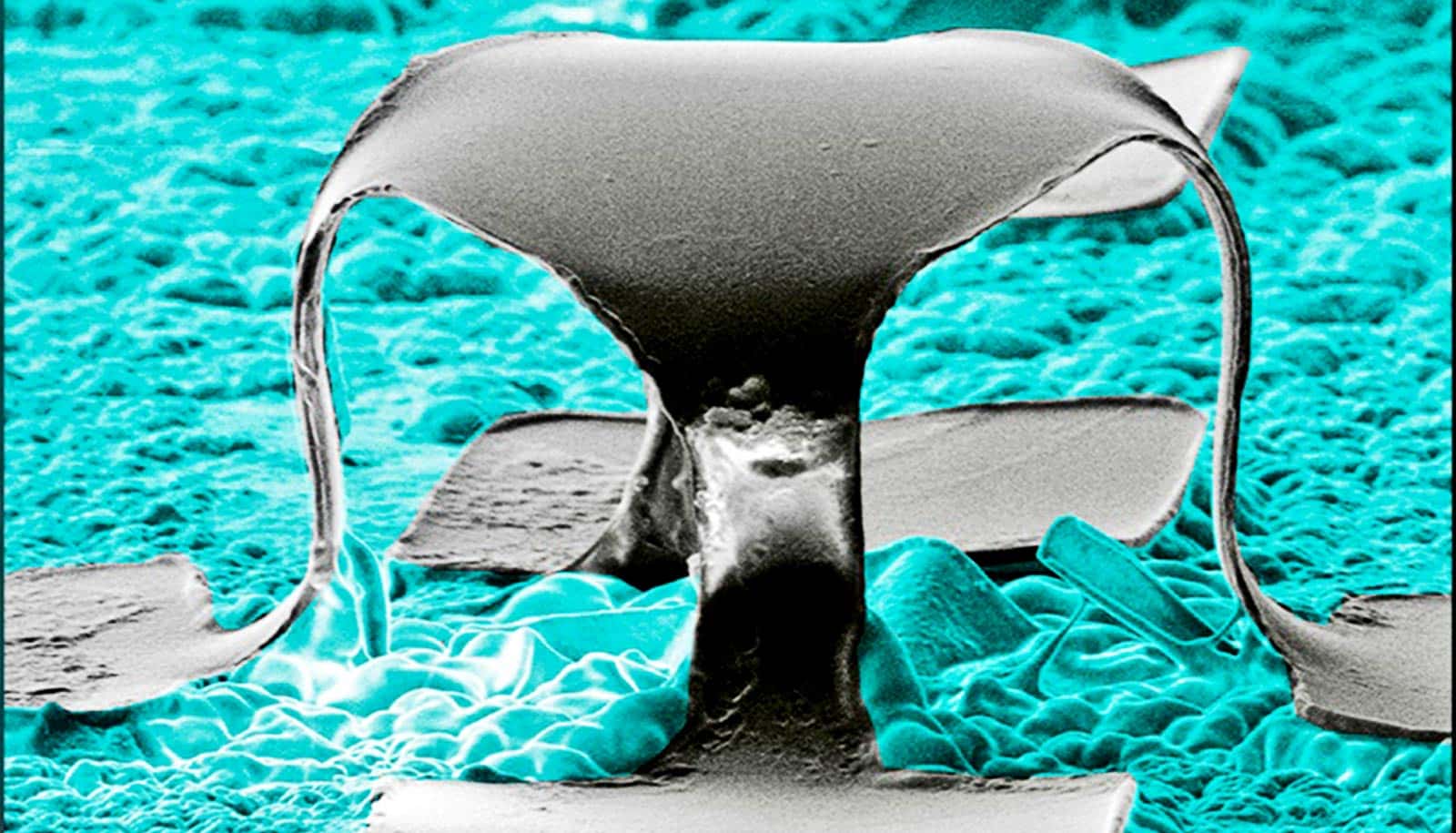

Using tiny pressure-sensing structures shaped like tables, Texas A&M University researchers found that repeated pushes on the tables’ flat surface don’t cause the structures to fall apart, even when the compressive forces are extreme. Instead, these tiny devices, including those with slight defects, were resilient, continuing to remain functional by bending their legs in proportion to the applied force.

The researchers say their findings have direct implications on the longevity of technologies that incorporate miniature devices, like soft wearable electronics, stretchable solar cells and pressure-sensing socks.

Miniature devices, like pressure sensors, need to faithfully convey the strength and a change in compressions. For many applications, sensors need to be very small to capture changes in pressure at a high enough resolution. Miniature devices based on the Japanese paper-cutting and folding technique of kirigami offer an excellent solution.

Borrowing the principles of kirigami, a design of the miniature device is first etched on a 2D surface. Then, an inward push from the design boundary makes the structure pop up. Other times, the 2D print is stretched or twisted to reveal a more intricate 3D design. Regardless of the final use, kirigami-based devices must face continuous distortions to their shape, a phenomenon engineers refer to as deformation.

“Part of the appeal of using kirigami structures is that they can be repeatedly deformed for extended periods of time,” says Andreas A. Polycarpou, professor and department head in the mechanical engineering department. “But any kind of imperfection in these structures might impact their final performance, that is, their ability to be continuously deformed.”

To investigate how defects might influence the function of kirigami devices, the researchers designed a set of experiments using tiny pressure sensors. Consisting of a flat surface supported by four legs, these structures buckle under pressure applied from above.

For their study, the researchers repeatedly pressed down on the table-like structures using a diamond flat punch probe. Their sample included structures with slight defects, such as a small crack on one of the four legs or one slightly thinner leg.

To test the performance of these structures over time, they recorded how these structures behaved under repeated compressions using an electron microscope and measured the distance the legs bent.

The researchers found that for both defect-free and defective kirigami structures, the compression caused the structures to “stiffen” or resist the downward force. Over time, however, even when compressive forces were extreme, the structures reached a steady-state and were able to recover from the repeated blows from the diamond punch.

The researchers say the results of their cyclic compression experiments suggest that systems with an assembly of kirigami devices can remain functional for a long period of time even if some of the devices within them have defects.

“For most applications, including pressure sensing, it’s not one but multiple miniature devices working in tandem. Intuitively one would think that small defects in any one of the kirigami structures would be catastrophic for a system made with many of such structures,” Polycarpou says.

“We now have evidence to show that they do not. So, if one is using smart socks to measure how pressure is distributed during gait, our results suggest that the miniature pressure sensors will still work remarkably well even if they are slightly defective.”

The research appears in the journal Extreme Mechanics Letters. Additional researchers are from Texas A&M, Bruker Nano Surfaces, Northwestern University, and Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

The Hagler Institute for Advanced Study at Texas A&M University funded the study.

Source: Texas A&M University