A new in vitro diagnostic test for COVID-19 could deliver results in less than 10 minutes, researchers say.

As COVID-19 cases spike, the need for faster, more accessible testing is clear. Limited availability, leaves many patients with symptoms—and their physicians—wondering whether they have the virus. Even when patients do get a test, overwhelmed labs can take several days to get the results.

The new test could change that.

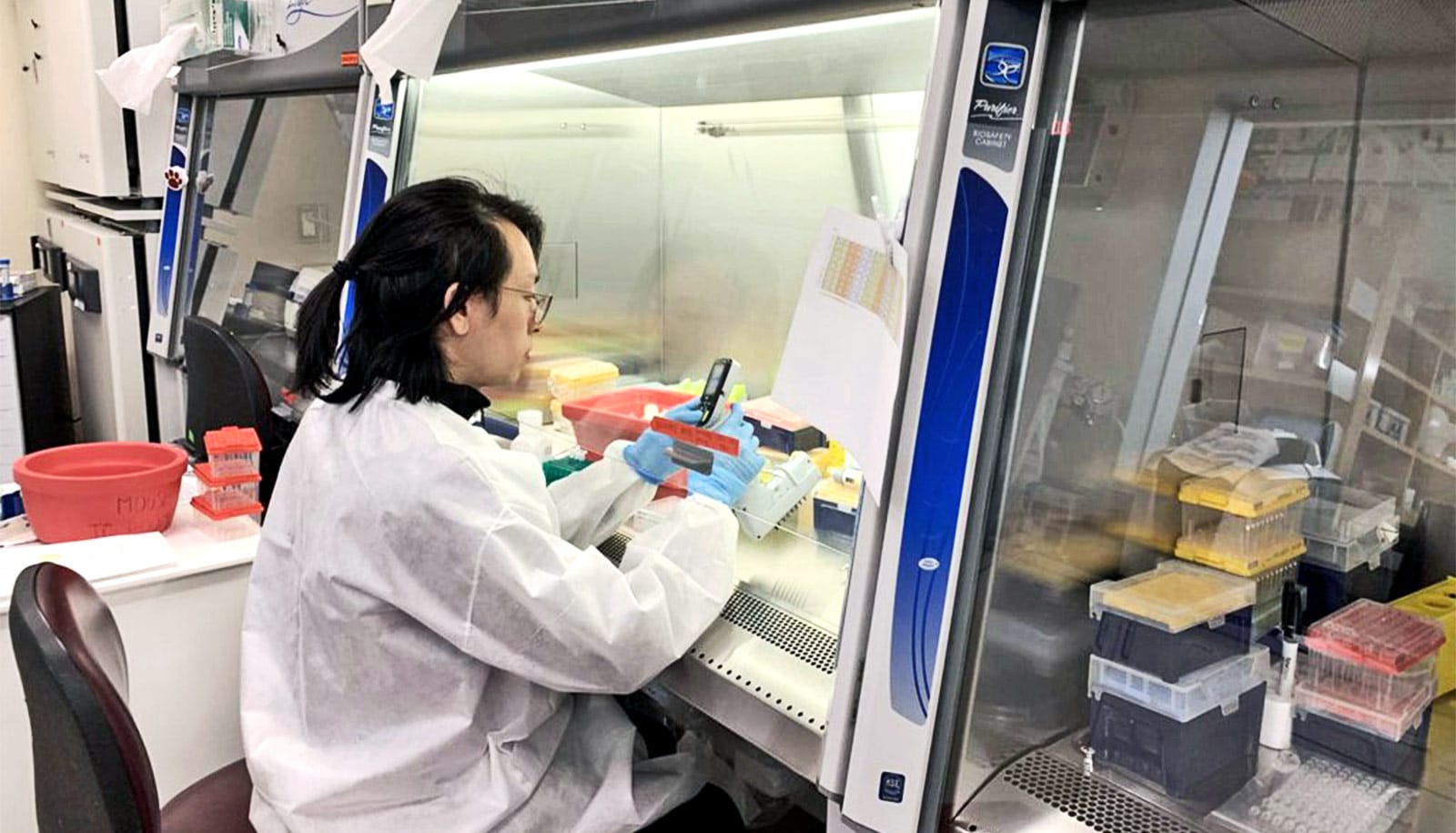

Brett Etchebarne, an emergency medicine physician and assistant professor in Michigan State University’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, wanted to create a COVID-19 test that emergency room doctors could perform on many patients in a short time, using equipment all hospitals have on hand. That way, doctors wouldn’t have to wait for an answer on whether a patient has COVID-19, allowing them to provide the right treatment and appropriate self-isolation guidelines before the patient leaves the hospital.

The test he created is fast. The FDA has already approved a few other rapid tests, but the number of tests performed at once is a limiting factor. Some only allow for one sample testing at a time, while others allow for up to four in specialized machines, but those remain in limited supply.

The new test can deliver results in five to seven minutes with the possibility of running higher numbers of tests at once.

And while it still needs validation, this new test likely won’t require an invasive nasal swab, Etchebarne says. Instead, health workers can do it with a simple mouth swab, making the sample collection process faster and less uncomfortable.

Etchebarne has worked in the field of rapid diagnostics of pathogens since 2011. Through his work, he has developed a rapid respiratory panel to screen for various common illnesses like pneumonia and the flu.

So, when the Centers for Disease Control released the genetic information on SARS-CoV2, the virus that causes COVID-19, it was a relatively quick process to adapt his testing method.

“I used what the CDC provided and made up my own primer sets, which are fragments of the target DNA or RNA that you can use to amplify a region of that genetic element,” Etchebarne says.

From there, determining the test result is simple. “It’s either there, or it’s not there,” he says.

Timing of the test’s availability remains uncertain, Etchebarne says. The next step is to get it validated in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments lab, a process currently underway.

Then, the test needs to get FDA approval. While there are many regulatory hoops to jump through, approval could happen in a matter of weeks, so he’s hopeful.

“We already know what to do, because we’ve been working on this kind of testing for a long time,” he says.

Source: Michigan State University