It’s time to rethink the relationship between employment and health care in the United States, a historian and public health expert argues.

Mical Raz is a professor in public policy and health, an assistant professor of history, and a board-certified internist at the University of Rochester Medical Center. She is the author of The Lobotomy Letters: the Making of American Psychosurgery (University of Rochester Press, 2015) and What’s Wrong with the Poor? Psychiatry, Race, and the War on Poverty. (University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Here, Raz explains why it’s time to uncouple the link between health insurance and work in America:

Over 3.2 million Americans filed unemployment claims last week, a 3 million increase from the previous week. Yet this staggering number is undoubtedly an underestimate. The enormous economic impact of these figures has a direct public health aspect—the loss of health insurance for many Americans who receive these benefits through their employer.

In the throes of a global pandemic, drastically increasing the number of uninsured Americans adds fuel to an already devastating fire. At the same time, the Trump administration has signaled that it has no intention to back off from its argument that the entirety of the Affordable Care Act is unconstitutional and should be struck down. The US Supreme Court should be hearing the case later this year, and while the legal arguments are astoundingly flimsy, there is no assurance that the law will be upheld.

The abrupt spike in the newly uninsured has the potential for a perfect storm, devastating to both individuals and hospitals, who will see soaring rates of uncompensated care. In the absence of health insurance, hospitals continue to provide acute care, but find that they often do not get paid for it.

There is no preordained reason health insurance should be tied to employment, and the United States is unique in its insistence on the primacy of this model. Nearly 60% of Americans obtain their health insurance through their employer, a statistic that should worry us all as we see the rising unemployment figures. Americans view health insurance, and thus access to health care, as a privilege earned through employment rather than a fundamental right, and attempts to alter this relationship have been met with intractable resistance.

Health insurance and employment

This employment-focused approach was not inevitable, but rather was meticulously cultivated by insurance companies, who had clear financial interests in mind. Insuring workers as a group was a powerful method of ensuring they would sell their policies to a relatively healthy, capable, and young population, thus keeping their expenses low and their profit margins high.

As historian David Rothman has shown, insurance companies marketed not only their product but also the cultural perception that insurance was an earned benefit, a responsibility that the head of the household needed to provide for his family. A father who could not take his child to the doctor because he had failed to obtain appropriate insurance was a sign of personal failure, rather than the failure of a society to care for its vulnerable.

By the 1960s, a majority of Americans received their health insurance through their employers, a development that began only in the early 1930s.

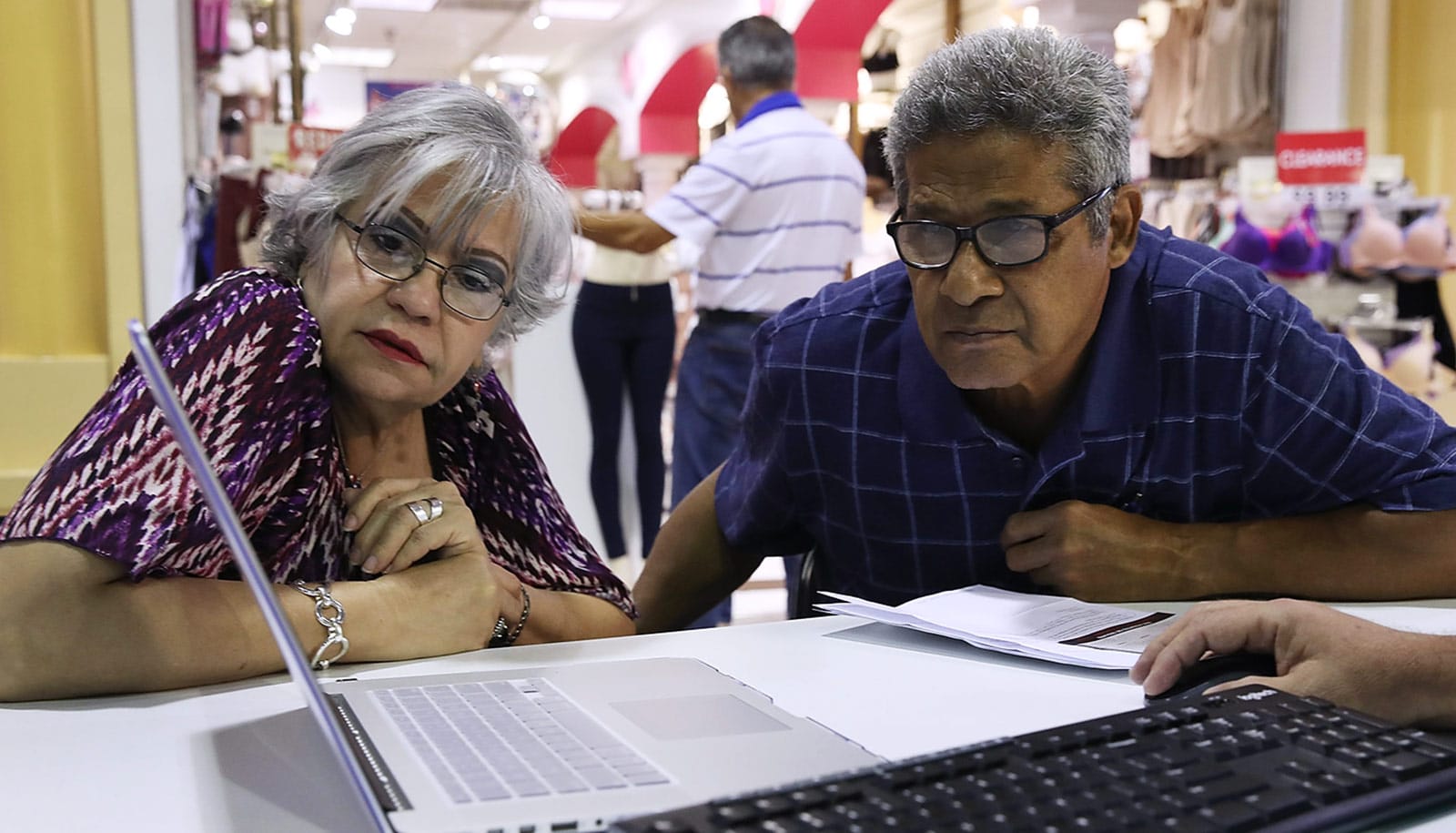

Yet, relying on employment as a method to obtain health insurance left many behind: the elderly, unemployed or those who cannot work for other reasons, and of course, children.

Specific programs were developed to address these populations—namely Medicare, Medicaid, and later the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Still any attempts to expand insurance through means unrelated to employment were met with fierce resistance. With the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which as designed would have required states to expand Medicaid eligibility to low-income Americans, 26 states successfully sued the federal government to avoid this requirement. While many initially reluctant states eventually chose to expand, to date, 14 states have not expanded Medicaid, leaving many low-income Americans uninsured.

Furthermore, under the Trump administration, states have successfully petitioned to add work requirements to Medicaid accessibility, a harmful and unproven measure, most recently struck down in Michigan by the US District Court in Washington, DC.

Who’s paying?

While employer sponsored health insurance is popular in the US, it is expensive, inefficient, and favors high earners. The average cost of an employer sponsored plan in 2019 was over $20,000 per family, a 5% increase from the previous year. While the employer pays much of this, on average over a quarter of premiums are paid by employees, in addition to ever-increasing copays, deductibles, and other forms of cost sharing.

When employers pay for their employees’ benefits, it’s at the expense of workers’ salaries. Yet these benefits are not taxed, a long-standing tax quirk that disproportionately benefits higher earners with higher tax brackets. Furthermore, there is little incentive for efficiency and cost-saving measures in employer-based insurance, as high spending on health insurance is simply translated into higher premiums.

Essentially, insurers benefit while taxpayers foot the bill.

Employment-sponsored insurance favors insurance companies and those in high-paying jobs. It has many downsides, including promoting job-lock, hindering innovation, and keeping salaries low. It also, as we see now, is incredibly ill-suited for a widespread public health catastrophe like the COVID-19 pandemic. As unemployment and ensuing rates of uninsured Americans are beginning to soar, it’s time to rethink this relationship between employment and healthcare.

Opinions can change, and we should not let the health insurance industry be the primary shaper of public opinion on who deserves health insurance. Expediency creates new priorities, and reshapes deep-seated political beliefs. I have a family member who peeled off a car sticker that had read “Obamacare works for those who don’t” and happily enrolled for a plan in the government exchange, when their workplace no longer offered insurance.

The aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic should be an opportunity to rethink our overreliance on employment as a measure of value, and as a gateway to healthcare. It’s time to ensure Americans can access healthcare regardless of their employment. Too much is at stake.

Source: University of Rochester