Colon cancer cells produce energy for growth differently in women and men, researchers report.

The difference is associated with a more aggressive form of tumor development with a higher incidence in women, according to the new study.

Researchers say this is the first significant documentation of a sex difference in colon cancer metabolism.

“With this new information and many promising leads, our work is helping to determine what can be done to prevent worse outcomes for women who develop this deadlier form of colon cancer,” says Caroline Johnson, assistant professor of epidemiology at Yale University School of Public Health and co-senior author of the study in Scientific Reports.

“This work will benefit all women, but particularly black women, who are at higher risk for colon cancer compared with other races or ethnic groups.”

Women have a lower rate of colon cancer than men but a higher prevalence of the right-sided type, a deadlier associated with a 20% increased risk of death compared with cancer of the left side.

Colorectal cancer, is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the US, with 145,600 new cases and 51,000 deaths each year.

Researchers found clues to the underlying mechanisms driving this difference in risk. Using new techniques collectively called “metabolomics,” they investigated the molecular products of digestion and cellular processes created by the foods people consume, their hormone production, and the specific bacteria residing inside the colon.

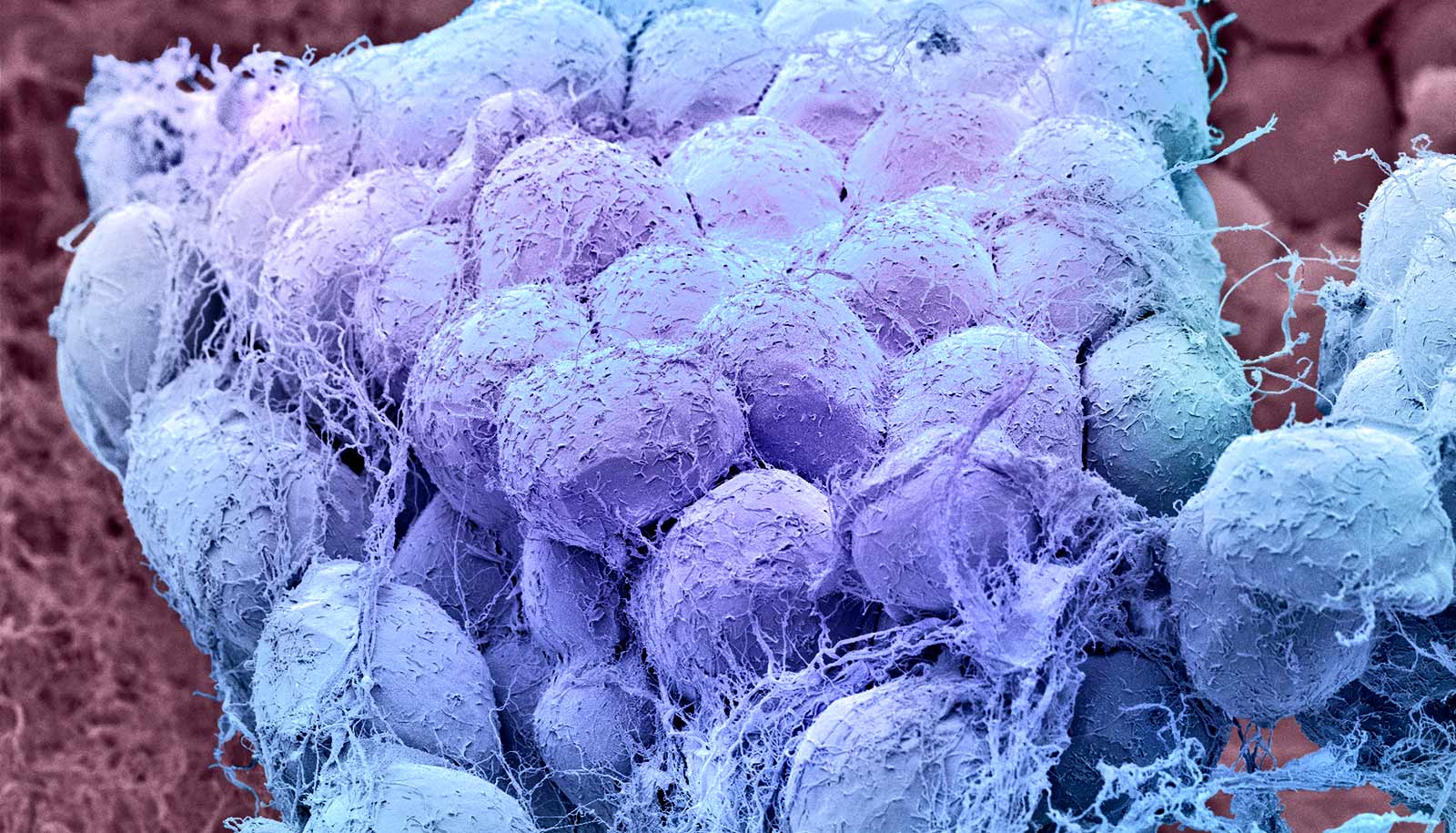

Examining normal colon and tumor tissue samples from women and men with colon cancer, the researchers analyzed concentrations and interactions of metabolites, the small chemicals such as sugars and amino acids which are transformed during metabolism.

The findings show that women with right-sided colon cancer have increased levels of metabolites known as fatty acids, which undergo a process known as fatty acid oxidation to produce energy.

Women also have increased levels of glutamine and asparagine, amino acids which research has linked to more aggressive tumor growth. In contrast, men with colon cancer have increased levels of metabolites such as lactate, which produce energy through a different pathway.

“These results indicate that colon cancer tumors grow differently in women and men and thus may require different approaches to stop their growth,” Johnson says.

In addition, the researchers examined clinical outcomes of patients, and found lower survival rates for women with colon cancer whose tumors showed a sex-specific molecular pathway for cellular energy production.

Johnson, in collaboration with co-senior author Sajid Khan, associate professor of surgery, aims to eventually identify a biological indicator to serve as a warning for the development of the deadlier right-sided colon cancer, which is more difficult to identify at early stages compared with left-sided colon cancer.

Women’s Health Research at Yale, the Yale Cancer Center, and the National Institutes of Health funded the work. Additional coauthors are from Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences in Scotland, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and Yale.

Source: Yale University