Boron nitride nanotubes encase tellurium atomic chains like a straw, which light and pressure could control, report researchers.

For wearable tech, electronic cloth, or extremely thin devices that can be laid over the surface of cups, tables, space suits, and other materials, researchers have begun to tune the atomic structures of nanomaterials.

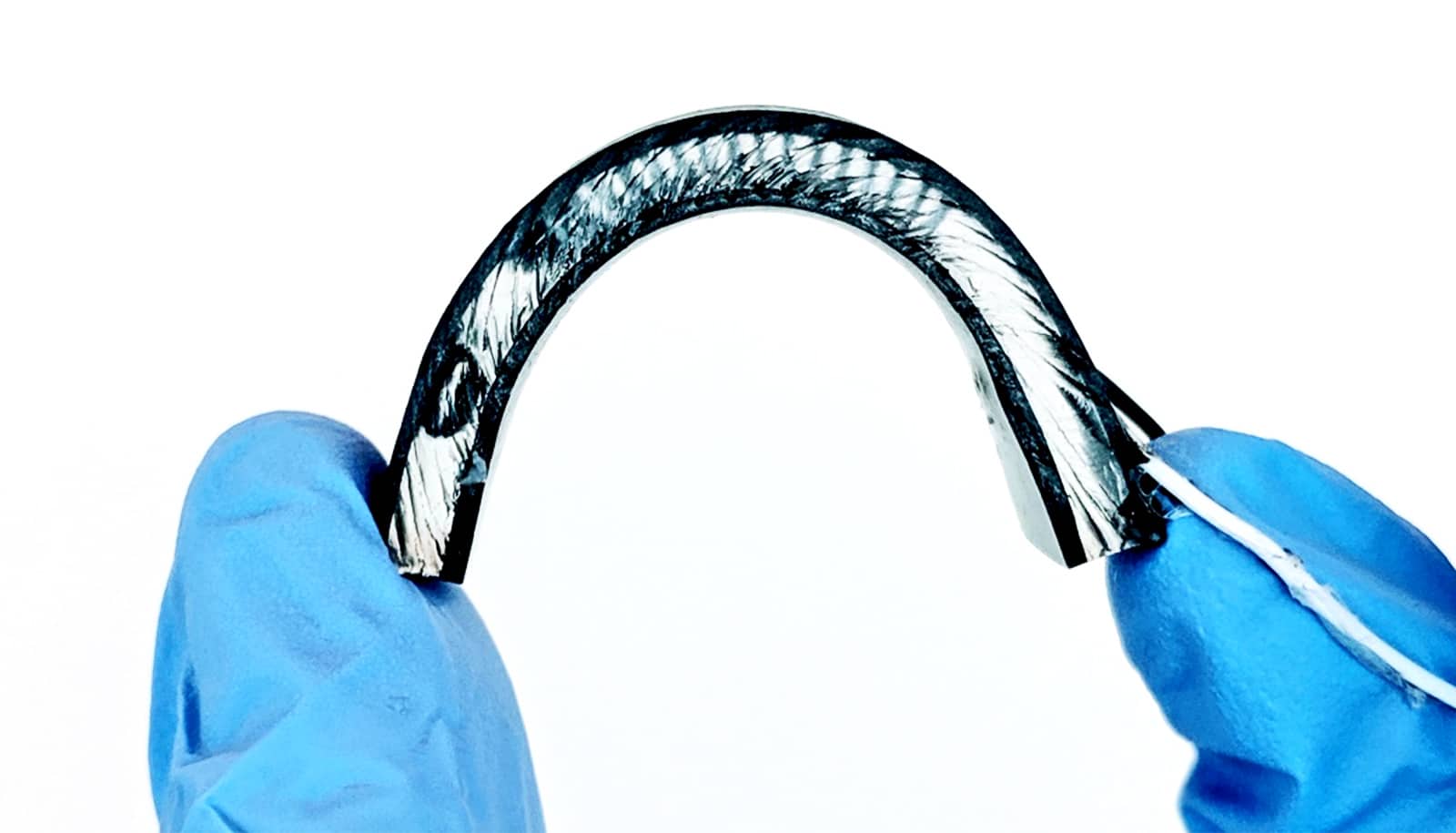

The materials they test need to bend as a person moves, but not go all noodly or snap, as well as hold up under different temperatures and still give enough juice to run the software functions users expect out of their desktops and phones. We’re not quite there with existing or preliminary technology—yet.

BNNTs have hollow centers

Yoke Khin Yap, professor of physics at Michigan Technological University, has studied nanotubes and nanoparticles—discovering the quirks and promises of their quantum mechanical behaviors. He pioneered using electrically insulating nanotubes for electronics by adding gold and iron nanoparticles on the surface of boron nitride nanotubes, or BNNTs. The metal-nanotube structures enhanced the material’s quantum tunneling, acting like atomic steppingstones that could help electronics escape the confines of silicon transistors that power most of today’s devices.

More recently, his group also created atomically thin gold clusters on BNNTs. As implied by the “tube” of their nanostructure, BNNTs are hollow in the middle. They’re highly insulating and as strong and bendy as an Olympic gymnast.

Tellurium atomic chains

That made them a good candidate to pair with another material with great electrical promise: tellurium. Strung into atom-thick chains, which are very thin nanowires, and threaded through the hollow center of BNNTs, tellurium atomic chains become a tiny wire with immense current-carrying capacity.

“Without this insulating jacket, we wouldn’t be able to isolate the signals from the atomic chains. Now we have the chance to review their quantum behavior,” Yap says. “This the first time anyone has created a so-called encapsulated atomic chain where you can actually measure them. Our next challenge is to make the boron nitride nanotubes even smaller.”

A bare nanowire is kind of a loose cannon. Controlling its electric behavior—or even just understanding it—is difficult at best when it’s in rampant contact with flyaway electrons. Nanowires of tellurium, which is a metalloid similar to selenium and sulfur, is expected to reveal different physical and electronic properties than bulk tellurium. Researchers just needed a way to isolate it, which BNNTs now provide.

“This tellurium material is really unique. It builds a functional transistor with the potential to be the smallest in the world,” says Peide Ye of Purdue University and lead researcher of the study, explaining that the team was surprised to find through transmission electron microscopy at the University of Texas at Dallas that the atoms in these one-dimensional chains wiggle. “Silicon atoms look straight, but these tellurium atoms are like a snake. This is a very original kind of structure.”

The tellurium-BNNT nanowires created field-effect transistors only 2 nanometers wide; current silicon transistors on the market are between 10 to 20 nanometers wide. The new nanowires current-carrying capacity reached 1.5×108 A cm-2, which also beats out most semiconducting nanowires. Once encapsulated, the team assessed the number of tellurium atomic chains held within the nanotube and looked at single and triple bundles arranged in a hexagonal pattern.

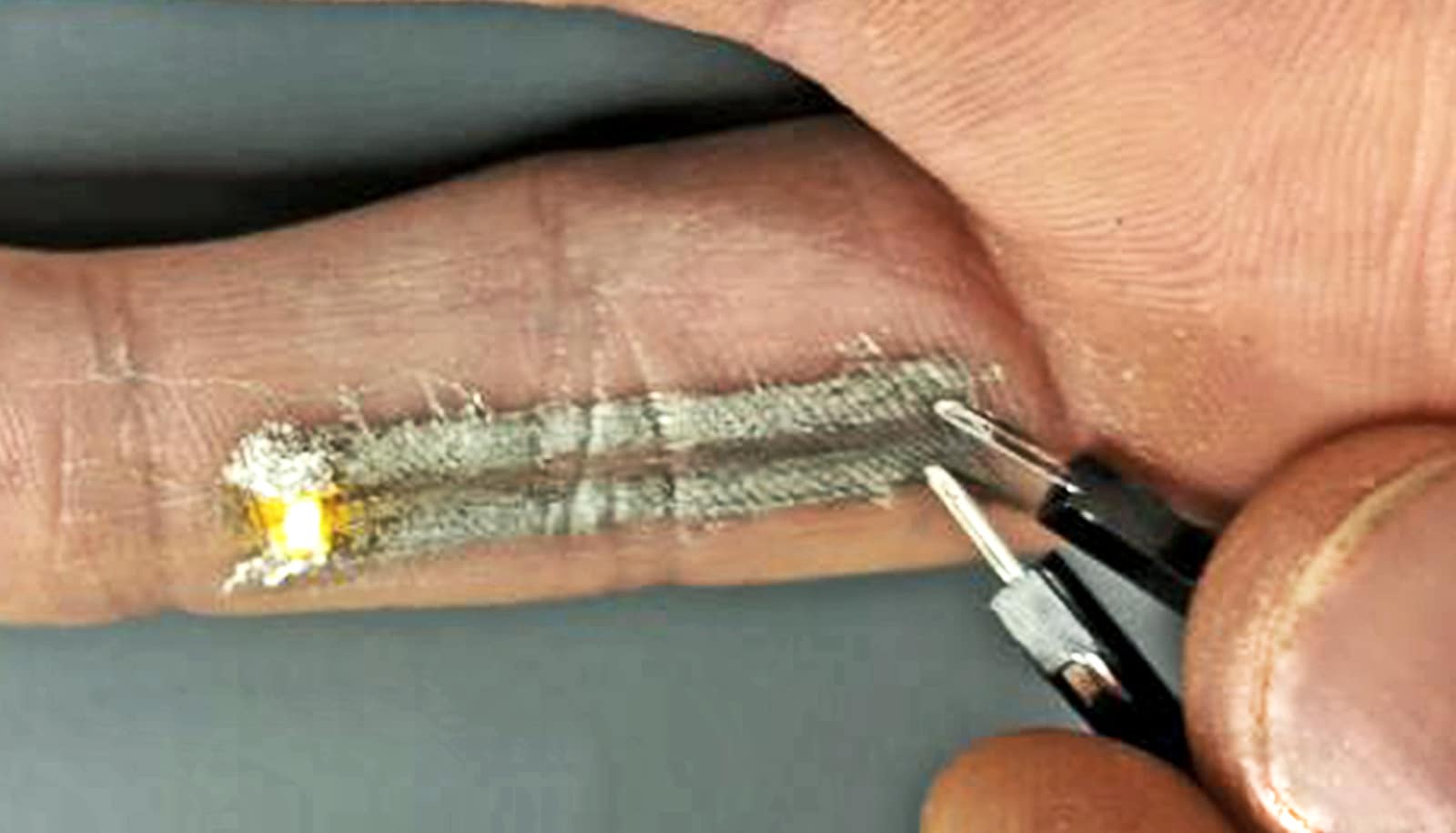

Additionally, the tellurium-filled nanowires are sensitive to light and pressure, another promising aspect for future electronics. The team also encased the tellurium nanowires in carbon nanotubes, but their properties are not measurable due to the conducting or semiconducting nature of carbon.

While the researchers have captured tellurium nanowires within BNNTs, much of the mystery remains. Before people begin sporting tellurium T-shirts and BNNT-laced boots, the nature of these atomic chains needs characterizing before its full potential for wearable tech and electronic cloth can be realized.

Researchers from Purdue, Washington University in St. Louis, and the University of Texas at Dallas report the findings in Nature Electronics.

Source: Michigan Tech