Methane levels in ancient air samples indicate that scientists have vastly underestimated how much of the greenhouse gas humans emit into the atmosphere via fossil fuels.

Methane is a large contributor to global warming. Methane emissions to the atmosphere have increased by approximately 150% over the past three centuries, but it has been difficult for researchers to determine exactly where these emissions originate; heat-trapping gases like methane can be emitted naturally, as well as from human activity.

“Placing stricter methane emission regulations on the fossil fuel industry will have the potential to reduce future global warming to a larger extent than previously thought,” says Benjamin Hmiel, a postdoctoral associate in the lab of Vasilii Petrenko, a professor of earth and environmental sciences at the University of Rochester. Hmiel, Petrenko, and colleagues report their findings in Nature.

Methane doesn’t stick around long

Methane is the second largest anthropogenic—human-caused—contributor to global warming after carbon dioxide. But, compared to carbon dioxide, as well as other heat-trapping gases, methane has a relatively short shelf-life; it lasts an average of only nine years in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, by contrast, can persist in the atmosphere for about a century. That makes methane an especially suitable target for curbing emission levels in a short time frame.

“If we stopped emitting all carbon dioxide today, high carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere would still persist for a long time,” Hmiel says. “Methane is important to study because if we make changes to our current methane emissions, it’s going to reflect more quickly.”

“…most of the methane emissions are anthropogenic, so we have more control.”

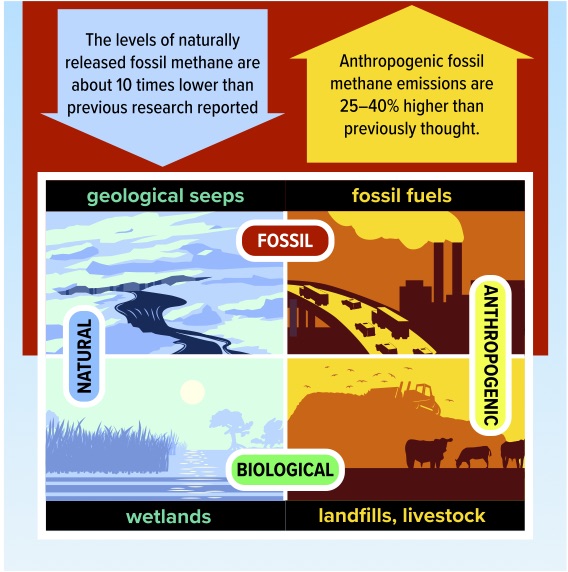

Methane emitted into the atmosphere can be sorted into two categories, based on its signature of carbon-14, a rare radioactive isotope. There is fossil methane, which has been sequestered for millions of years in ancient hydrocarbon deposits and no longer contains carbon-14 because the isotope has decayed; and there is biological methane, which is in contact with plants and wildlife on the planet’s surface and does contain carbon-14.

Biological methane can release naturally from sources such as wetlands or via anthropogenic sources such as landfills, rice fields, and livestock. Fossil methane, which is the focus of Hmiel’s study, can emit from natural geologic seeps or as a result of humans extracting and using fossil fuels including oil, gas, and coal.

Scientists are able to accurately quantify the total amount of methane emitted to the atmosphere each year, but it is difficult to break down this total into its individual components: Which portions originate from fossil sources and which are biological? How much methane is released naturally and how much is released by human activity?

“As a scientific community we’ve been struggling to understand exactly how much methane we as humans are emitting into the atmosphere,” says Petrenko, a coauthor of the study. “We know that the fossil fuel component is one of our biggest component emissions, but it has been challenging to pin that down because in today’s atmosphere, the natural and anthropogenic components of the fossil emissions look the same, isotopically.”

Ice cores as time capsules

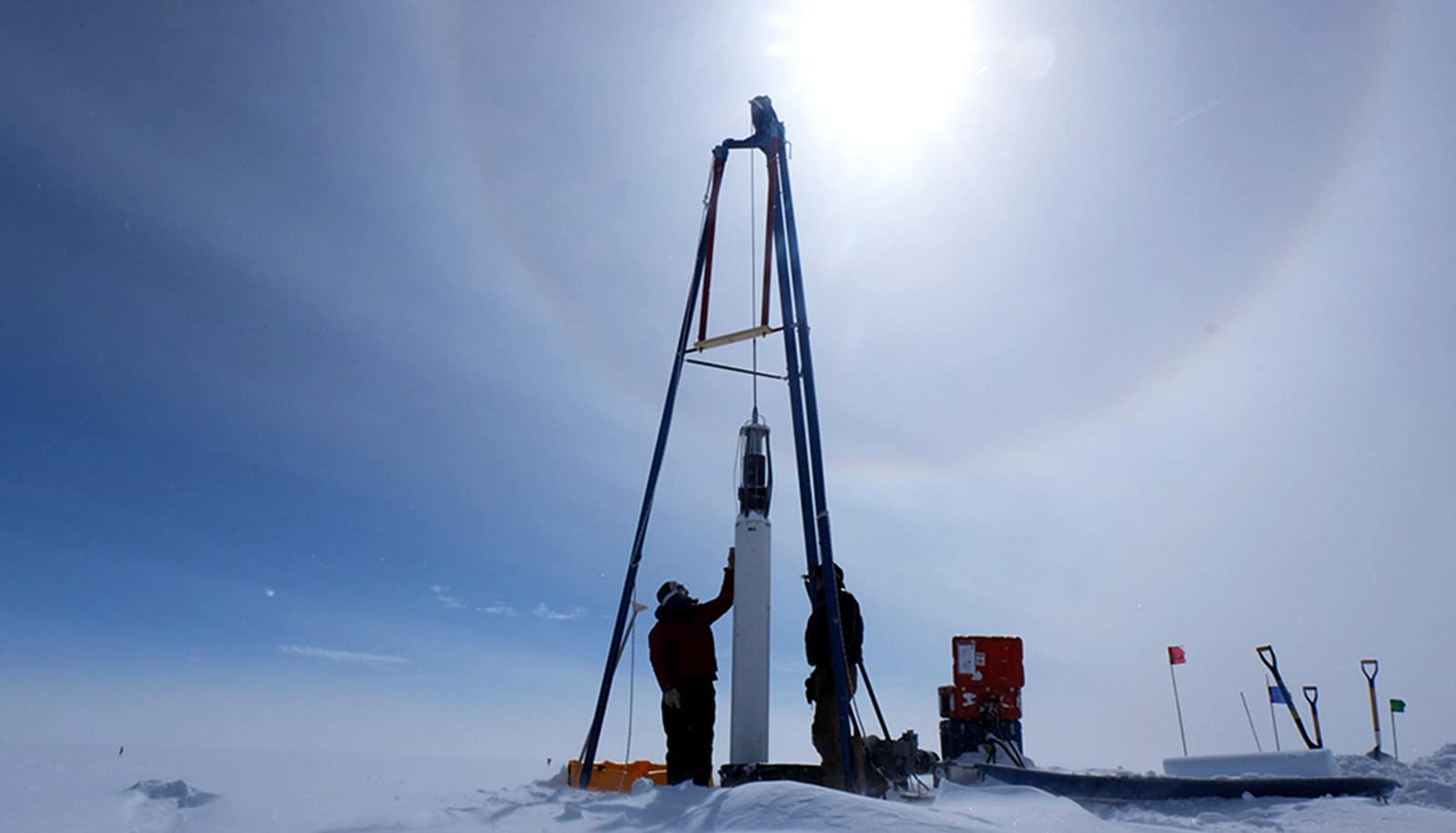

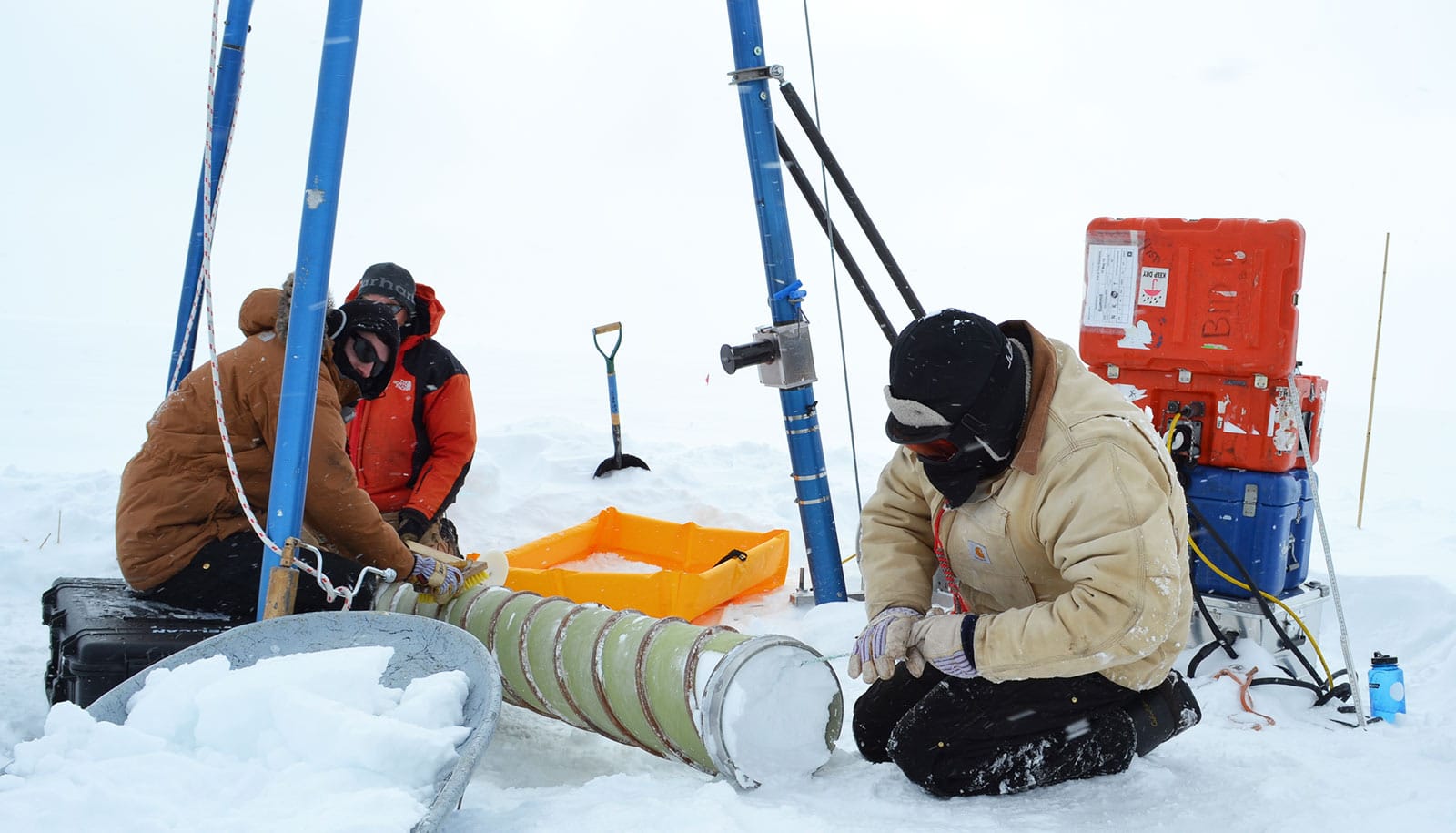

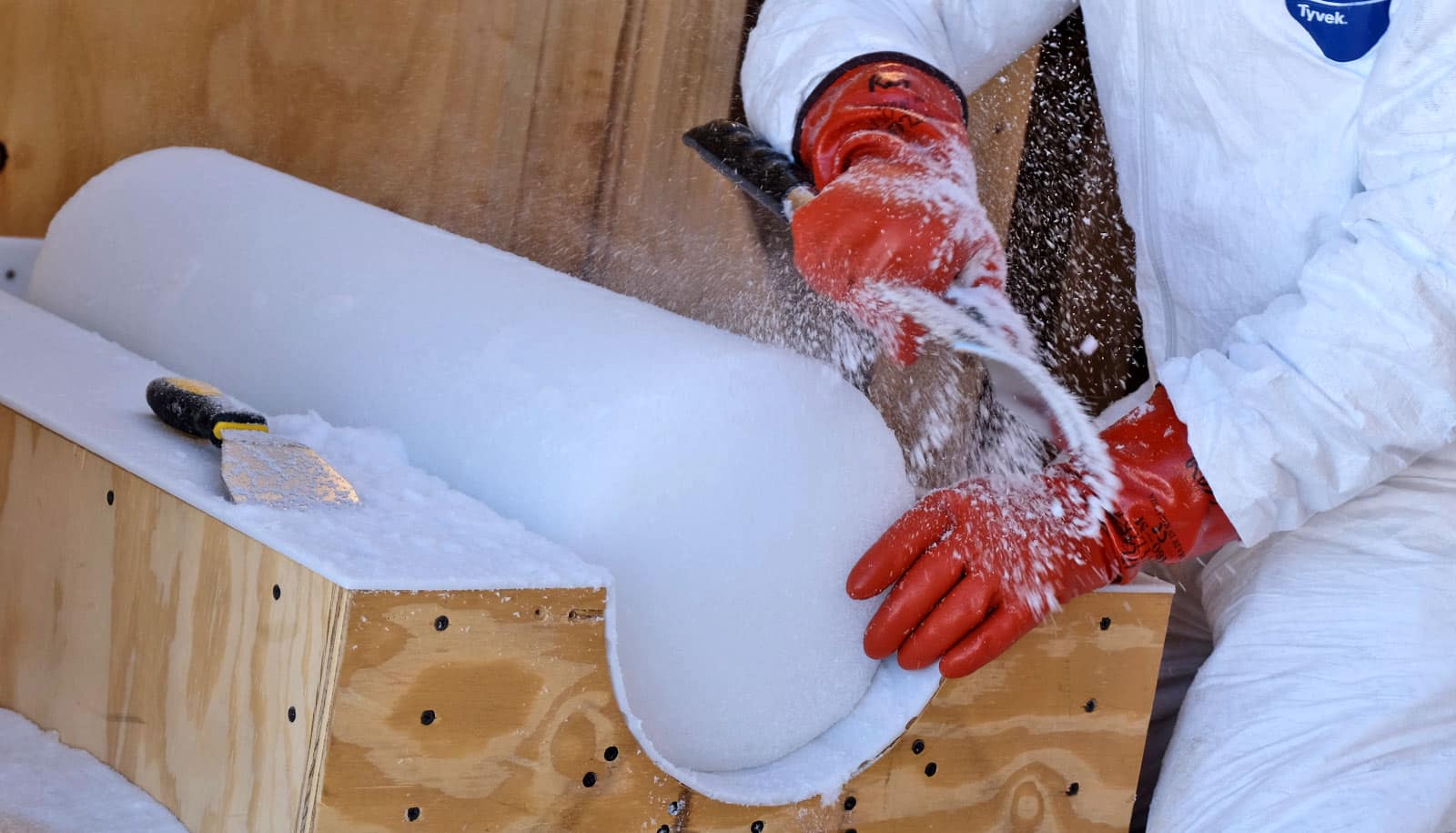

In order to more accurately separate the natural and anthropogenic components, Hmiel and his colleagues turned to the past by drilling and collecting ice cores from Greenland. The ice core samples act like time capsules: they contain air bubbles with small quantities of ancient air trapped inside. The researchers use a melting chamber to extract the ancient air from the bubbles and then study its chemical composition.

Hmiel’s research focused on measuring the composition of air from the early 18th century—before the start of the Industrial Revolution—to the present day. Humans did not begin using fossil fuels in significant amounts until the mid-19th century. Measuring emission levels before this time period allows researchers to identify the natural emissions absent the emissions from fossil fuels that are present in today’s atmosphere. There is no evidence to suggest natural fossil methane emissions can vary over the course of a few centuries.

By measuring the carbon-14 isotopes in air from more than 200 years ago, the researchers found that almost all of the methane emitted to the atmosphere was biological in nature until about 1870. That’s when the fossil component began to rise rapidly. The timing coincides with a sharp increase in the use of fossil fuels.

The levels of naturally released fossil methane are about 10 times lower than previous research reported. Given the total fossil emissions measured in the atmosphere today, Hmiel and his colleagues deduce that the human-caused fossil component is higher than expected—25-40% higher, they find.

Are the findings good news?

The data have important implications for climate research: if anthropogenic methane emissions make up a larger part of the total, reducing emissions from human activities like fossil fuel extraction and use will have a greater impact on curbing future global warming than scientists previously thought.

To Hmiel, that’s actually good news. “I don’t want to get too hopeless on this because my data does have a positive implication: most of the methane emissions are anthropogenic, so we have more control. If we can reduce our emissions, it’s going to have more of an impact.”

The US National Science Foundation and the David and Lucille Packard Foundation supported the work.

Source: University of Rochester