Civil War refugee camps show how African Americans built a future from the ashes of slavery, a historian explains.

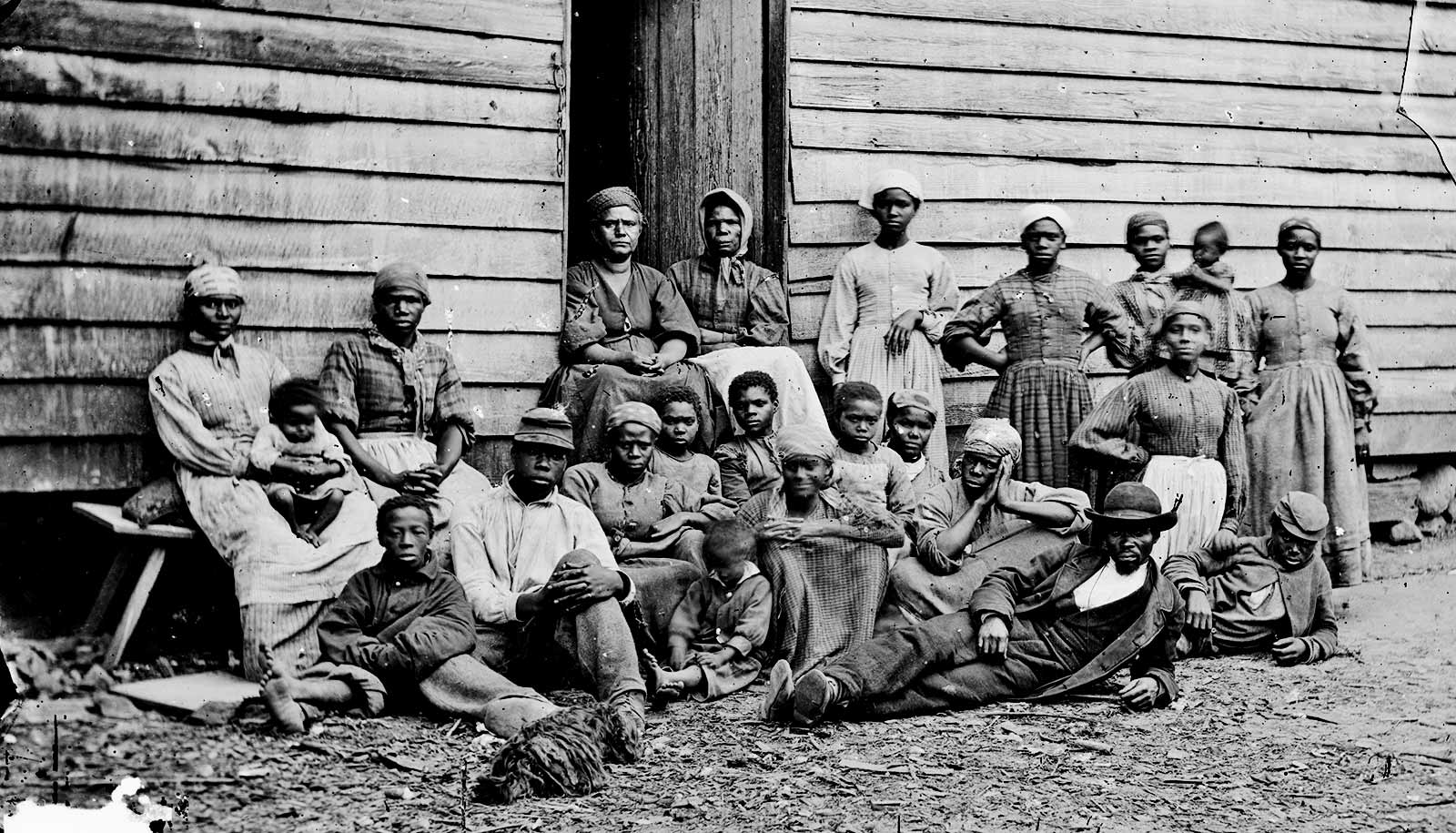

More than 300 refugee camps sprang up during the war with more than 800,000 African Americans passing through them at some point. Most residents were slaves or ex-slaves fleeing the clutches of their enslavers and the Confederate army, estimates Abigail Cooper, an assistant professor of history at Brandeis University who has a joint appointment in African and African American Studies.

Others came to find family members who had been sold to different slave owners.

“By looking at this in-between moment when slavery’s end was possible but not assured, we can look to how African Americans made and lived out freedom on their own terms,” Cooper says.

“African Americans gathered to forge a monumental psychological transformation from knowing America as their enslaver to envisioning America as their home.”

Cooper wrote about the camps in her 2015 PhD dissertation and more recently in the Journal of African American History.

Mary Armstrong’s story

In 1863, newly freed from bondage and living in St. Louis, 17-year-old Mary Armstrong did the unthinkable—she journeyed to the slave-holding South.

Armstrong, one of more than 2,000 former slaves who told their stories to the New Deal’s Federal Writers’ Project in the late 1930s, had been separated from her parents as a child when they were sold to other owners.

Armstrong learned through the grapevine that her kin might be in Texas so, as she says in her interview, “away I goin’ to find my mamma.”

With the Civil War raging, she set out with two baskets full of food and clothing and a small amount of money, traveling more than 1,000 miles by boat and then stagecoach to Texas.

In Austin, she was captured and put up for bid, securing her freedom only at the last minute by showing her papers to the Texas official in charge of the auction.

Armstrong eventually found her mother in the city of Wharton, some 150 miles south of Austin, at a refugee camp for African Americans.

Armstrong described the reunion: “Lawd me, talk ’bout cryin’ and singin’ and cryin’ some more, we sure done it.”

Armstrong later went on to become a nurse in the Houston area, saving numerous lives in the yellow fever epidemic of 1875.

What were the refugee camps like?

A camp could hold anywhere from a few hundred to several thousand people, most of them living in barracks or fabric tents.

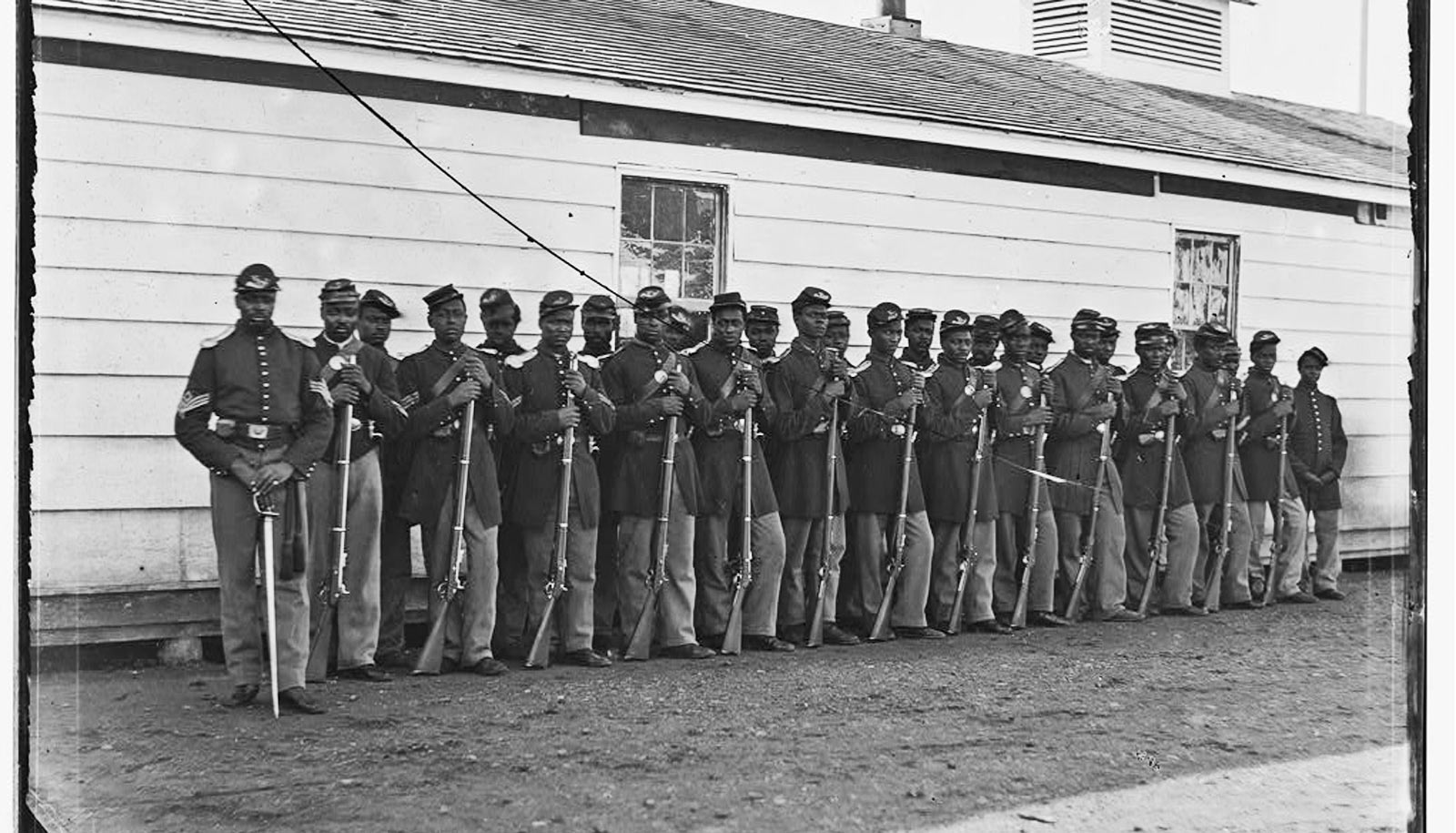

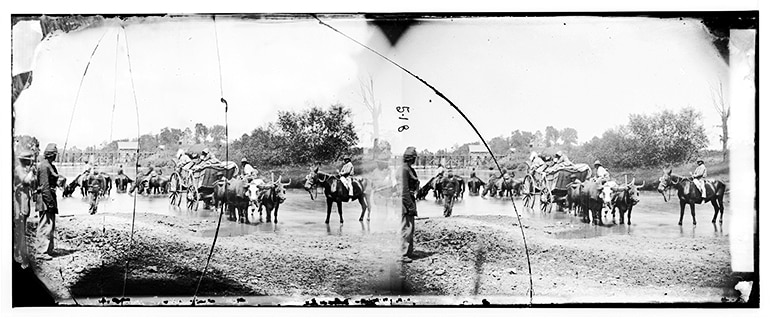

The Union set up some of the camps, the first two in 1861 along the coast in Virginia and South Carolina, followed by others in Kentucky and Tennessee and along the Mississippi River from New Orleans to St. Louis, Missouri. Officially, they were called “contraband camps,” because freed people were considered property confiscated from the South.

Another group of camps located mainly in the South behind Confederate lines was created ad hoc by blacks themselves. (Cooper has posted an interactive map of the locations of the camps).

At a camp in Hampton, Virginia called Slabtown and later the Grand Contraband Camp, African Americans built houses so sturdy the Union later appropriated them to house troops.

There were also four black schools in the camp, one of which became the future site of Hampton University, one of the premier historically black educational institutions in the country.

Life as a refugee

Conditions in many of the camps were squalid and disease was common. Black refugees lived in constant fear and terror of raids from southern whites. At one point, the Confederate army plundered and burned Slabtown to the ground.

Whites also lived in the camps, most of them seeking shelter from the war. They were treated differently from blacks. A rations list Cooper discovered for a camp in New Bern, North Carolina, shows that 1,800 whites received 76½ barrels of flour over the course of three months in 1862-63. During the same period, the 7,500 blacks there received 19 barrels.

But despite the hardships and oppression, Cooper says that the camps offered the formerly enslaved people their first opportunity to savor freedom, reunite as families and lay the groundwork for a new society and religion.

Never before had so many former slaves of so many different cultures gathered in such concentrations with the possibility of freedom near. There was an exchange of ideas, traditions, and rituals that fostered literacy and education and led to religious revivals.

Camp inhabitants compared their plight to the Israelites in the desert in the book of Exodus, freed from slavery but not yet delivered to their new country.

“More than anything, we should make careful study of the remarkable amount of resourcefulness it took for refugee slaves to gather their families into Union lines, to build information networks, to pray, eat, hoe, sing, give birth, share living space, take care of each other’s children, to imagine home while in a place outside a ‘household,'” Cooper wrote in her dissertation.

Over and over again, the residents in the camps talk about the importance of shoes. On plantations, masters kept slaves’ footwear locked up at night so they couldn’t escape. A good pair of shoes was necessary to make the difficult trek, sometimes through forests and rocky terrain, to the camps. Without shoes, you could more easily be picked out in a crowd as an escaped slave, and kidnappers lurked, attempting to sell people back into slavery.

Refugees carried money and protective charms in their shoes. They also fashioned footwear from plantain leaves. Their pungent smell was useful in throwing off the scent of the hounds patrollers and former owners used to track them down.

A common song went, “I got shoes, you got shoes, All o’ God’s chillun got shoes. When I get to heav’n I’m goin’ to put on my shoes.”

Religious freedom

Cooper says folk religion informed black visions for their new society. Emancipation as a divine reckoning was the lens through which they defined liberty. Freedom meant the right to practice their religion.

It was through refugee camps, Cooper wrote in her thesis, that black refugees “sought to transform the Egypt of the Slave South into a New Canaan.”

“Their great soul-hungering desire was freedom.”

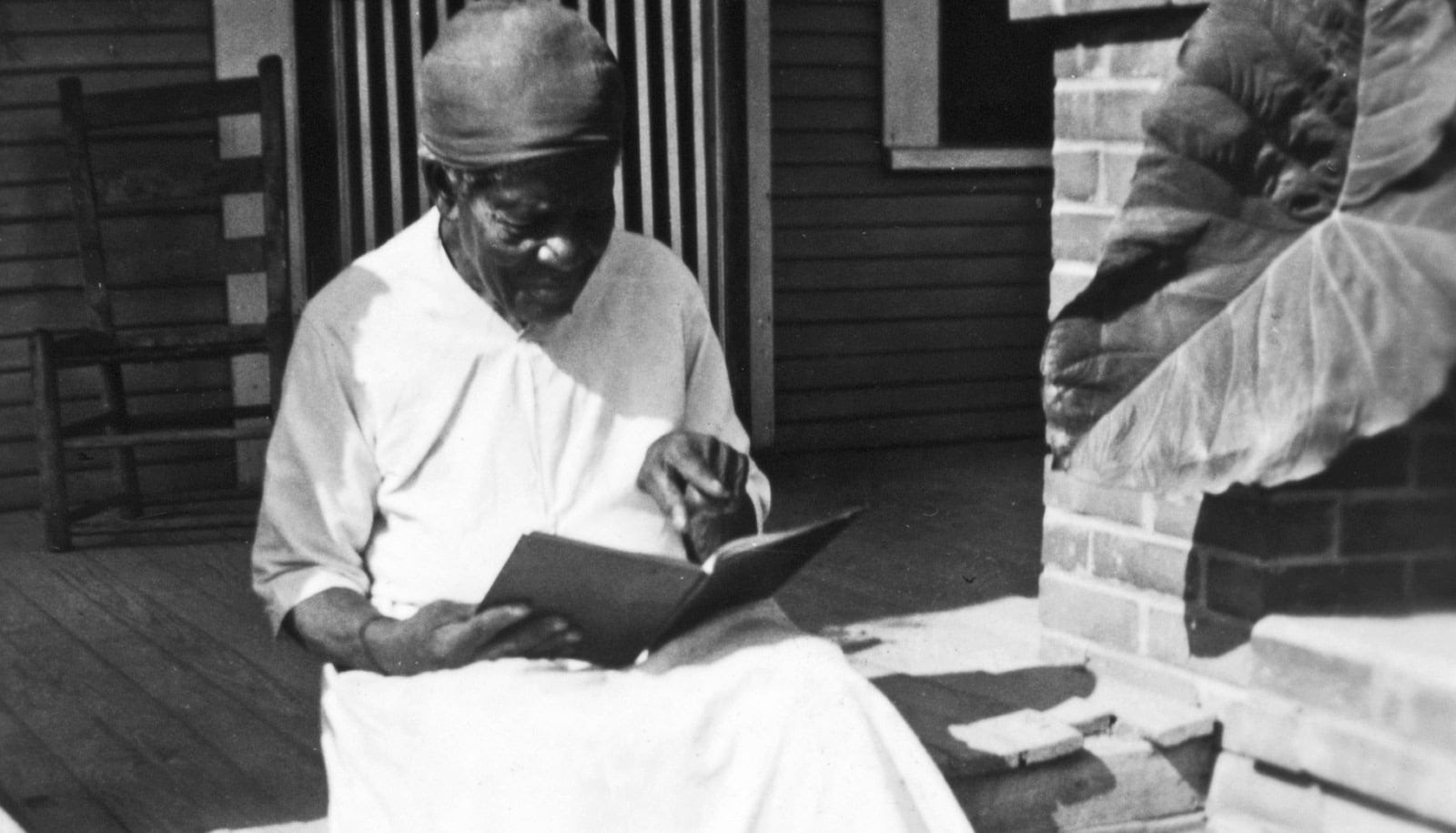

Critical to this was the ability to read the Bible for themselves for the first time in their lives. Southern slaveholders had used selected passages to justify slavery.

African Americans in the camps now formed Bible study groups and found scripture to support their liberation. The Jubilee in the Old Testament marks the day when Hebrew slaves would be freed from bondage in Egypt. African Americans created their own Emancipation Jubilee on January 1, 1863, the day the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

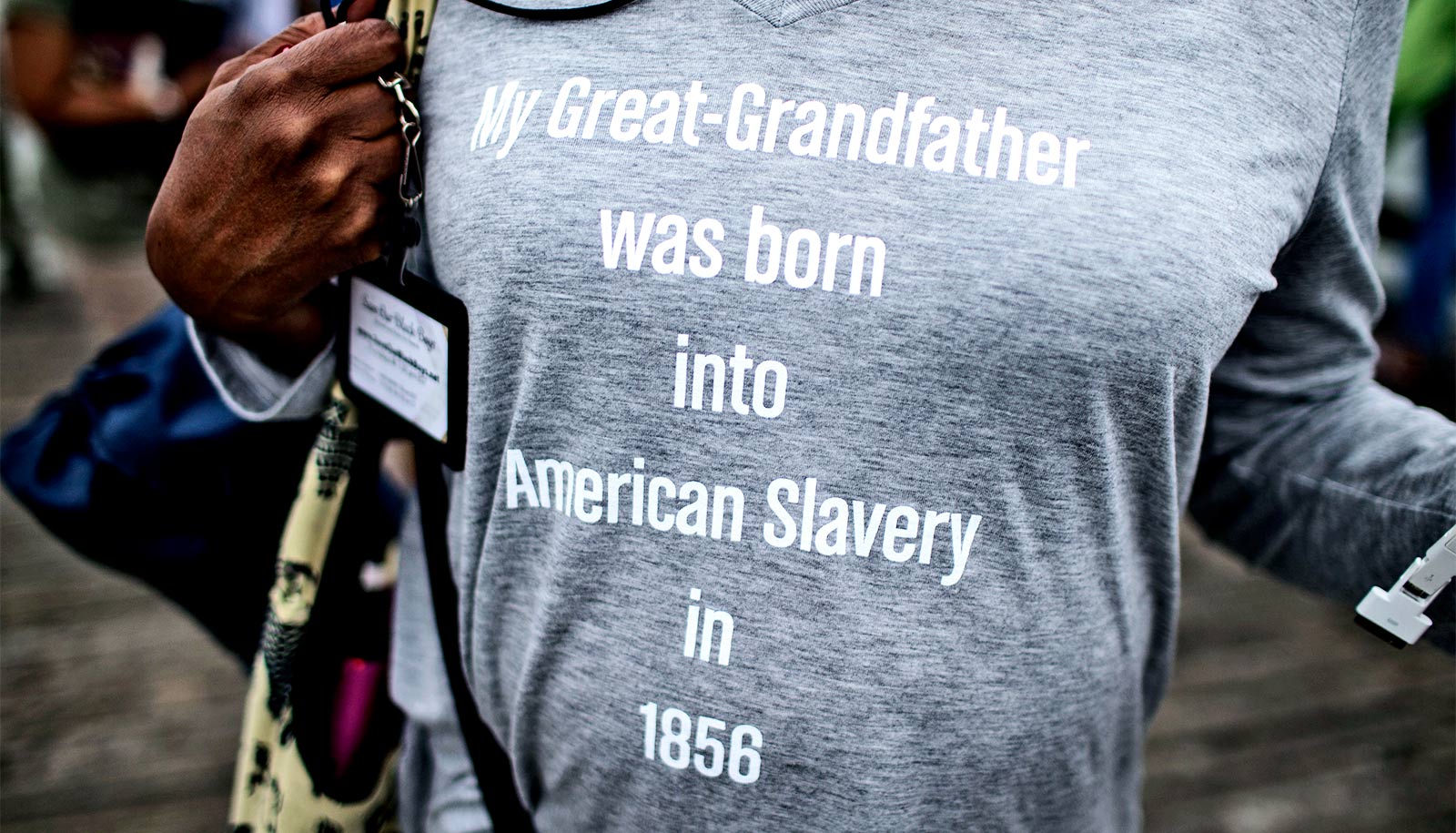

Another jubilee was celebrated in 1865 with the passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery. And a grand jubilee celebrated annually well into the 20th century as “Juneteenth” commemorated June 19th, 1865, when word of southern surrender reached black camps in Texas.

Grieving was an all too common experience in the camps, but black refugees in the camps turned mourning rituals into opportunities for empowerment. “There was all this death going on around them,” Cooper says, “but they were dying in freedom, and that meant something. Many saw going back to slavery as even worse.”

One woman who had three of her children die in a camp expressed relief because she knew where her children were buried. If they had been sold away from her, she would not know whether they lived or died or how to mourn them.

In what were called “watch meetings” or “watch-night meetings” or “setting up,” adults at all-night funerals danced, clapped, prayed, and experienced ecstatic visions.

“The slaves would sing, pray, and relate experiences all night long,” former slave Mary Gladdy says. “Their great soul-hungering desire was freedom.”

Jennie Boyd’s story

Jennie Boyd’s contractions had already started when her family realized they had to move on. She had been hiding out in Springfield, Missouri, but now her owners were close to finding her. Meanwhile, the Wilson’s Creek battle on August 10, 1861, raged nearby, making it dangerous to stay any longer.

The Boyds headed west toward Arizona accompanied at times by a retreating regiment of the Confederate army. Jennie told her 4-year-old daughter Emma to stay close and not go near anything that was smoking in case it was an explosive.

Jennie was in full labor by the time the family arrived in Bethphage, some 80 miles to the southwest. It was little more than a camping ground in the wilderness, but it was here that Jennie gave birth.

The baby was born “sick and delicate,” Emma later recalled, but she survived. Jennie honored the camp by naming her newborn after it—Priscilla Bethpage.

The Boyds continued west but soon crossed paths with a band of Union soldiers who offered to take them back to Springfield where one of Jennie’s other daughters remained enslaved. The family found refuge there in the home of a white Union sympathizer.

When the war ended in 1865, the family moved to a black settlement known as “Dink-town” in central Arkansas. Emma says freed people there “dug holes in the ground, made dug-outs, brush houses, with a piece of board here and there, whenever they could find one, until finally they had a little village.”

They were staking their claims on making homes in freedom as best they could. It was here, Emma says, that “they sang and prayed and rejoiced.”

Views of freedom

Cooper’s research points to a new way of understanding the political emancipation of African Americans. Often cast in terms of African Americans winning the right to vote or running candidates for office, Cooper believes there were other, equally fundamental ways that blacks viewed freedom.

Freedom had a spiritual dimension that fueled a radical transformation of what it meant to be a black American.

“W.E.B. DuBois says it almost a century ago: ‘To most of the four million black folk emancipated by the Civil War, God was real,'” Cooper says.

“The postwar period will present new forms of oppression and exploitation, but black Americans will still celebrate emancipation and how they made it. This will feed their ongoing freedom struggle and their resilience,” she says.

Source: Brandeis University