Hundreds of newly discovered and unusually large bacteriophages have capabilities normally associated with living organisms, researchers report.

Researchers found the huge bacteriophages, viruses that “eat” bacteria, by scouring a large database of DNA generated from nearly 30 different environments, ranging from the guts of premature infants and pregnant women to a Tibetan hot spring, a South African bioreactor, hospital rooms, oceans, lakes, and deep underground.

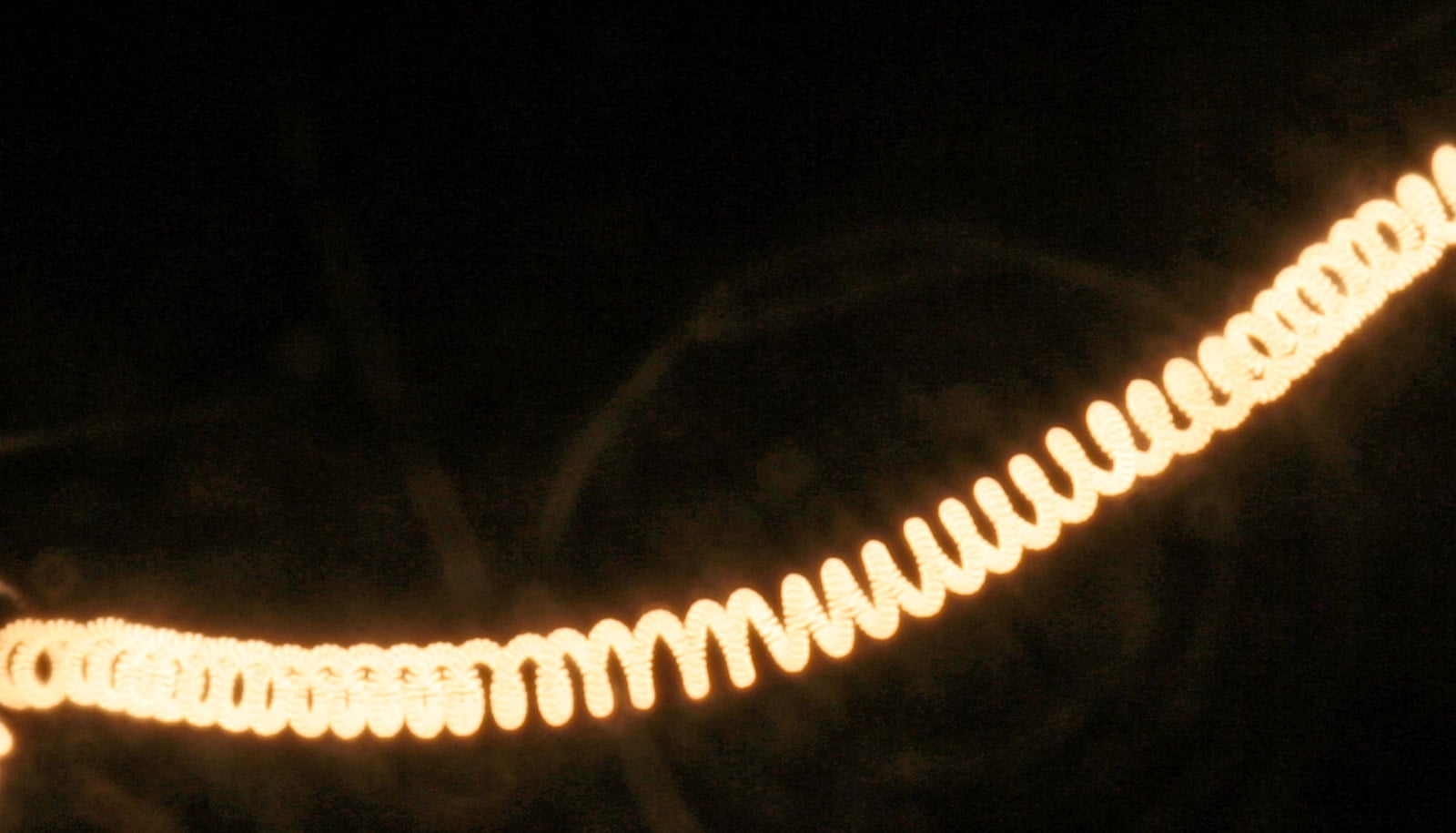

The phages are of a size and complexity considered typical of life, carry numerous genes normally found in bacteria, and use these genes against their bacterial hosts.

“We are exploring Earth’s microbiomes and sometimes unexpected things turn up.”

The findings provide new insight into the constant warfare between phages and bacteria.

The researchers identified 351 different huge phages, all with genomes four or more times larger than the average genomes of viruses that prey on bacteria.

Among the discovery was the largest bacteriophage to date: its genome, 735,000 base-pairs long, is nearly 15 times larger than the average phage. This largest known phage genome is much larger than genomes of many bacteria.

“We are exploring Earth’s microbiomes and sometimes unexpected things turn up,” says senior author Jill Banfield, a professor of earth and planetary science and environmental science, policy, and management at University of California, Berkeley who did much of the work on the phages while she was the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Melbourne. “These viruses of bacteria are a part of biology, of replicating entities, that we know very little about.

“These huge phages bridge the gap between non-living bacteriophage, on the one hand, and bacteria and Archaea (the diversity of bacteria),” she says. “There definitely seems to be successful strategies of existence that are hybrids between what we think of as traditional viruses and traditional living organisms.”

The new findings also have implications for human disease. Viruses in general carry genes between cells, including genes that confer resistance to antibiotics. And since phages occur wherever bacteria and Archaea live, including the human gut microbiome, they can carry damaging genes into the bacteria that colonize humans.

“Some diseases are caused indirectly by phages, because phages move around genes involved in pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance,” says Banfield. “And the larger the genome, the larger capacity you have to move around those sorts of genes, and the higher the probability that you will be able to deliver undesirable genes to bacteria in human microbiomes.”

The findings appear in Nature. Additional researchers from the University of Melbourne and the UC Berkeley contributed to the work.

Source: University of Melbourne