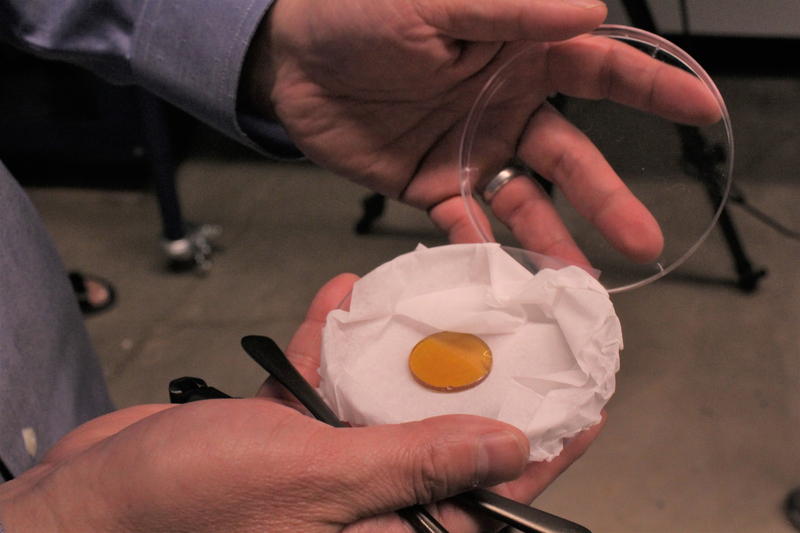

A new kind of plastic is incredibly useful for lenses, windows, and other devices requiring transmission of infrared light, which makes heat visible.

In the five years since researchers created the material, a sulfur-based polymer they forged from waste generated by refining fossil fuels, the team has improved the material and created the next generation of lenses.

“IR imaging technology is already used extensively for military applications such as night vision and heat-seeking missiles,” says Jeffrey Pyun, a professor in the chemistry and biochemistry department at the University of Arizona who leads the lab that developed the polymer. “But for consumers and the transportation sector, cost limits high-volume production of this technology.”

The new lens material could make infrared (IR) cameras and sensor devices more accessible to consumers, according to Robert Norwood, a professor in the James C. Wyant College of Optical Sciences. Potential consumer applications include economical autonomous vehicles and in-home thermal imaging for security or fire protection.

Better than before

The new polymers are stronger and more temperature resistant than the first-generation sulfur plastic researchers developed in 2014 that was transparent to mid-IR wavelengths. The new lenses are transparent to a wider spectral window, extending into the long-wave IR, and are far less expensive than the current industry standard of metal-based lenses made of germanium, an expensive, heavy, rare, and toxic material.

Because of germanium’s many drawbacks, first author Tristan Kleine, a graduate student in Puyn’s lab, identified a sulfur-based plastic as an attractive alternative. However, the ability to make IR-transparent plastics is a tricky business.

The components that give rise to useful optical properties, such as sulfur-sulfur bonds, also compromise the strength and temperature resistance of the material. Moreover, the inclusion of additional organic molecules to give the material strength resulted in reduced transparency, since nearly all organic molecules absorb IR light, Kleine says.

To overcome the challenge, Kleine—in collaboration with chemistry graduate student Meghan Talbot and chemistry and biochemistry professor Dennis Lichtenberger—used computational simulations to design organic molecules that were not IR-absorbing and predicted transparency of candidate materials.

“It could have taken years to test these materials in the laboratory, but we were able to greatly accelerate new materials design using this method,” Kleine says.

Germanium requires temperatures greater than 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit to melt and shape, but because of its chemical makeup, researchers can shape the sulfur polymer lenses at a much lower temperature.

The future of infrared

“A major advantage of these new sulfur-based plastics is the ability to readily process these materials at much lower temperatures than germanium into useful optical elements for cameras or sensors, while still maintaining good thermomechanical properties to prevent cracking or scratches,” Pyun says. “This new material has just checked so many boxes we couldn’t before.”

“Its reliability is essentially equivalent to optical polymers that are routinely used for eyeglasses,” Norwood adds.

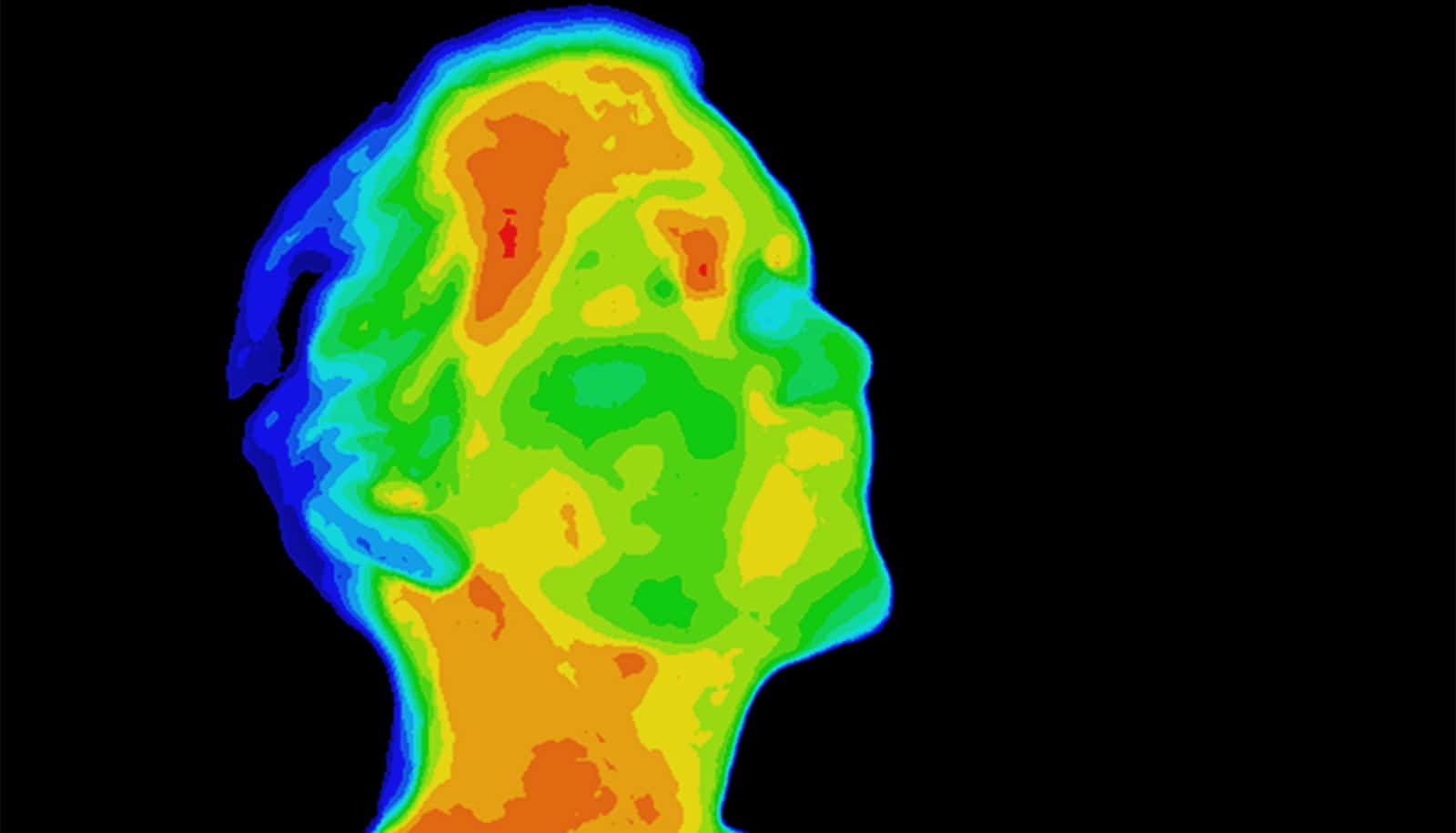

“Humans light up like a Christmas tree in IR,” Pyun says. “So, as we think about the Internet of Things and human-machine interfaces, the use of IR sensors is going to be a really important way to detect human behavior and activity.”

Researchers from the University of Delaware and Seoul National University also contributed to the paper, which was published today in the journal Angewandte Chemie.

The team is partnering with Tech Launch Arizona to translate the research into a viable technology.

Source: University of Arizona