Researchers believe they’ve overcome a major hurdle that’s kept perovskite solar cells from achieving mainstream use.

Perovskites are crystals with cube-like lattices known to be efficient light harvesters—but light, humidity, and heat tend to stress them out.

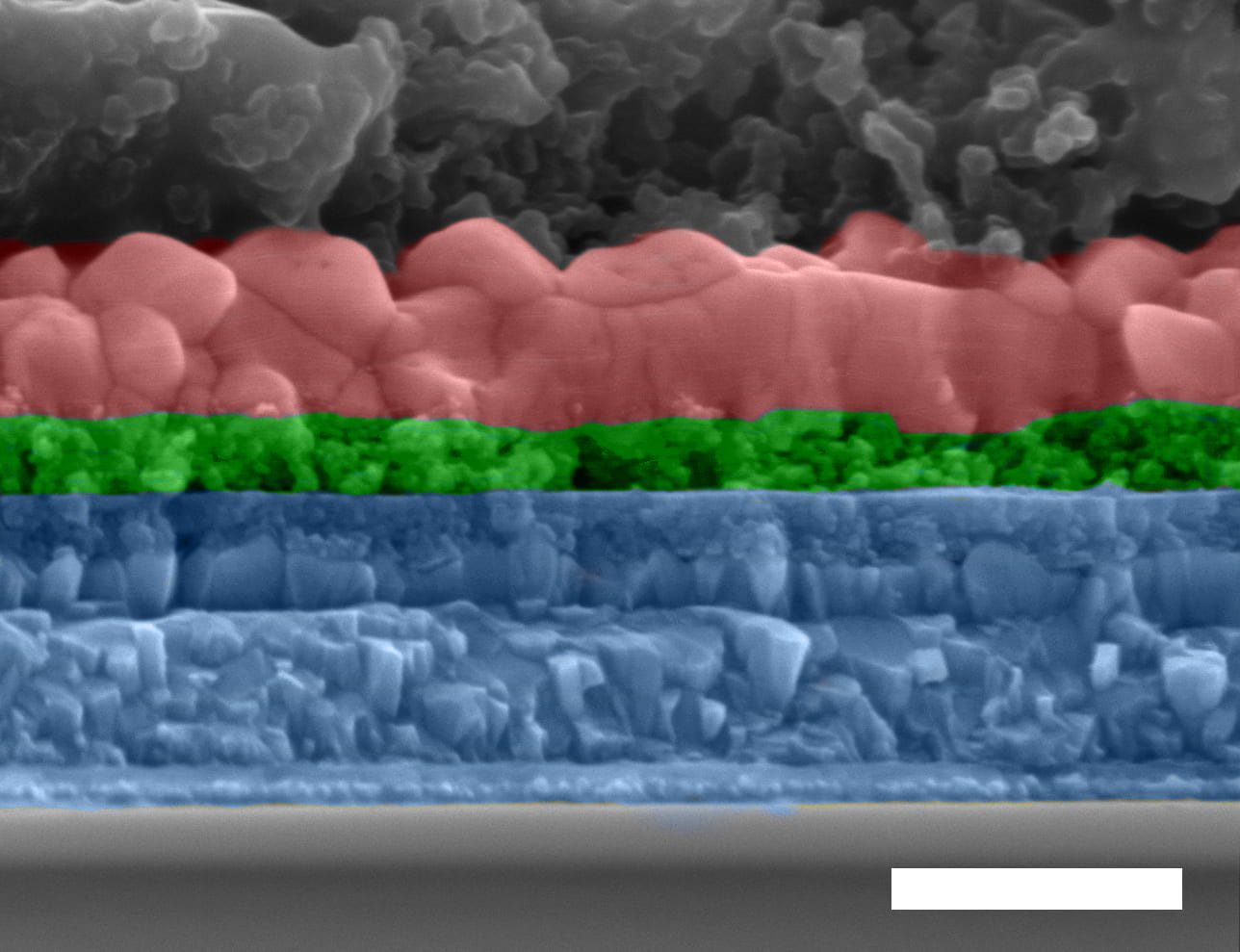

Through the strategic use of the element indium to replace some of the lead in perovskites, the researchers say they’re better able to engineer the defects in cesium-lead-iodide solar cells that affect the compound’s band gap, a critical property in solar cell efficiency.

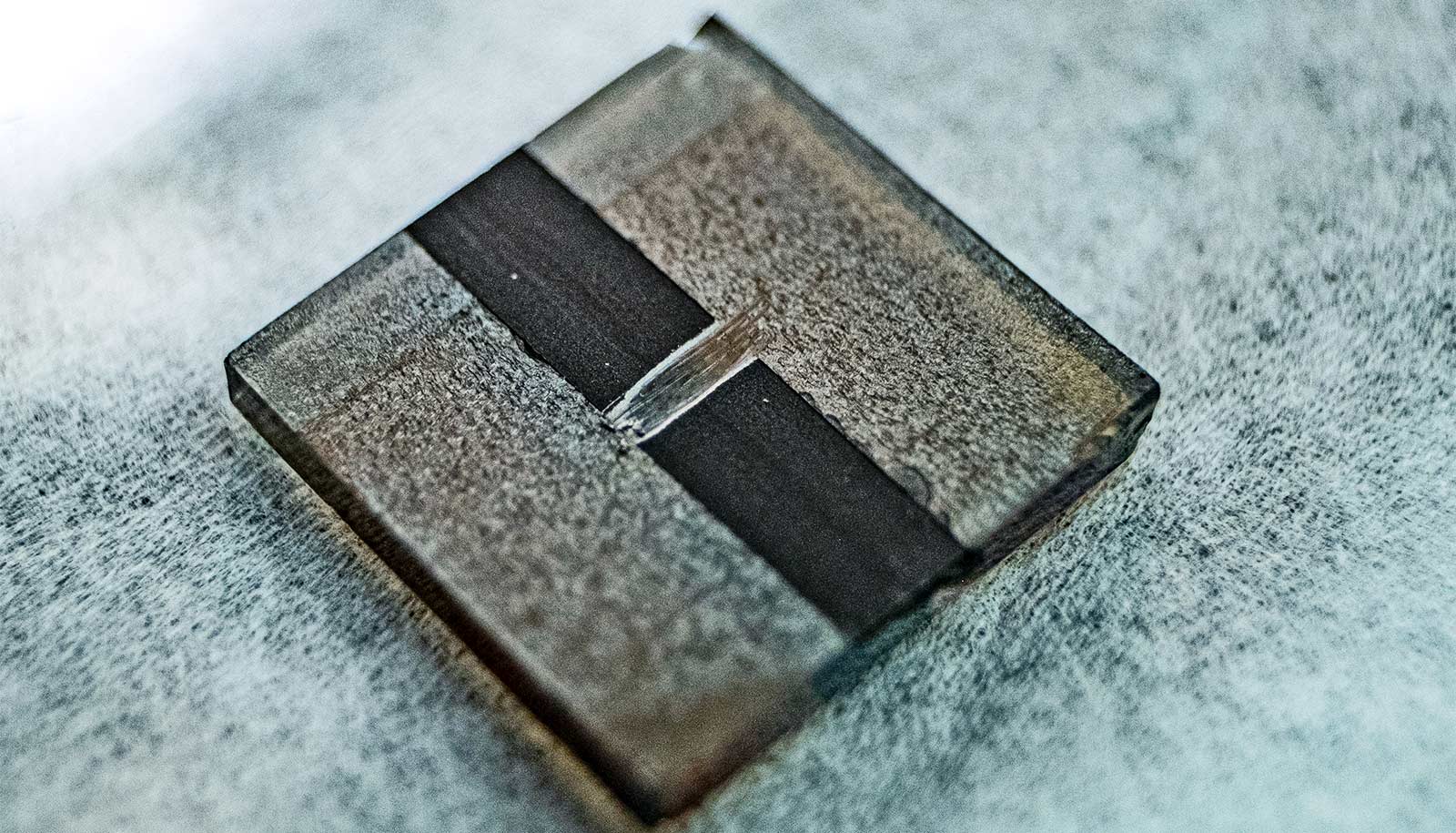

As a side benefit, the newly formulated cells can be made in open air and last for months rather than days with a solar conversion efficiency slightly above 12%.

“From our perspective, this is something new and I think it represents an important breakthrough,” says Jun Lou a materials scientist at Rice University.

“This is different from the traditional, mainstream perovskites people have been talking about for 10 years—the inorganic-organic hybrids that give you the highest efficiency so far recorded, about 25%. But the issue with that type of material is its instability,” he says.

“Engineers are developing capping layers and things to protect those precious, sensitive materials from the environment. But it’s hard to make a difference with the intrinsically unstable materials themselves. That’s why we set out to do something different.”

Lead author and postdoctoral researcher Jia Liang and his team built and tested perovskite solar cells of inorganic cesium, lead, and iodide, the very cells that tend to fail quickly due to defects. Adding bromine and indium allowed the researchers to quash defects in the material, raising the efficiency above 12% and the voltage to 1.20 volts.

As a bonus, the material proved to be exceptionally stable. Researchers prepared them in ambient conditions—and they stood up to Houston’s high humidity. Encapsulated cells remained stable in air for more than two months, far better than the few days that plain cesium-lead-iodide cells lasted.

“The highest efficiency for this material may be about 20%, and if we can get there, this can be a commercial product,” Liang says. “It has advantages over silicon-based solar cells because synthesis is very cheap, it’s solution-based, and easy to scale up. Basically, you just spread it on a substrate, let it dry out, and you have your solar cell.”

The results appear in Advanced Materials.

Additional coauthors are from Northwestern Polytechnical University; Fudan University, Shanghai; and Rice University. The Peter M. and Ruth L. Nicholas Postdoctoral Fellowship in Nanotechnology, the Welch Foundation, the China Scholarship Council, and the National Science Foundation supported the work.

Source: Rice University