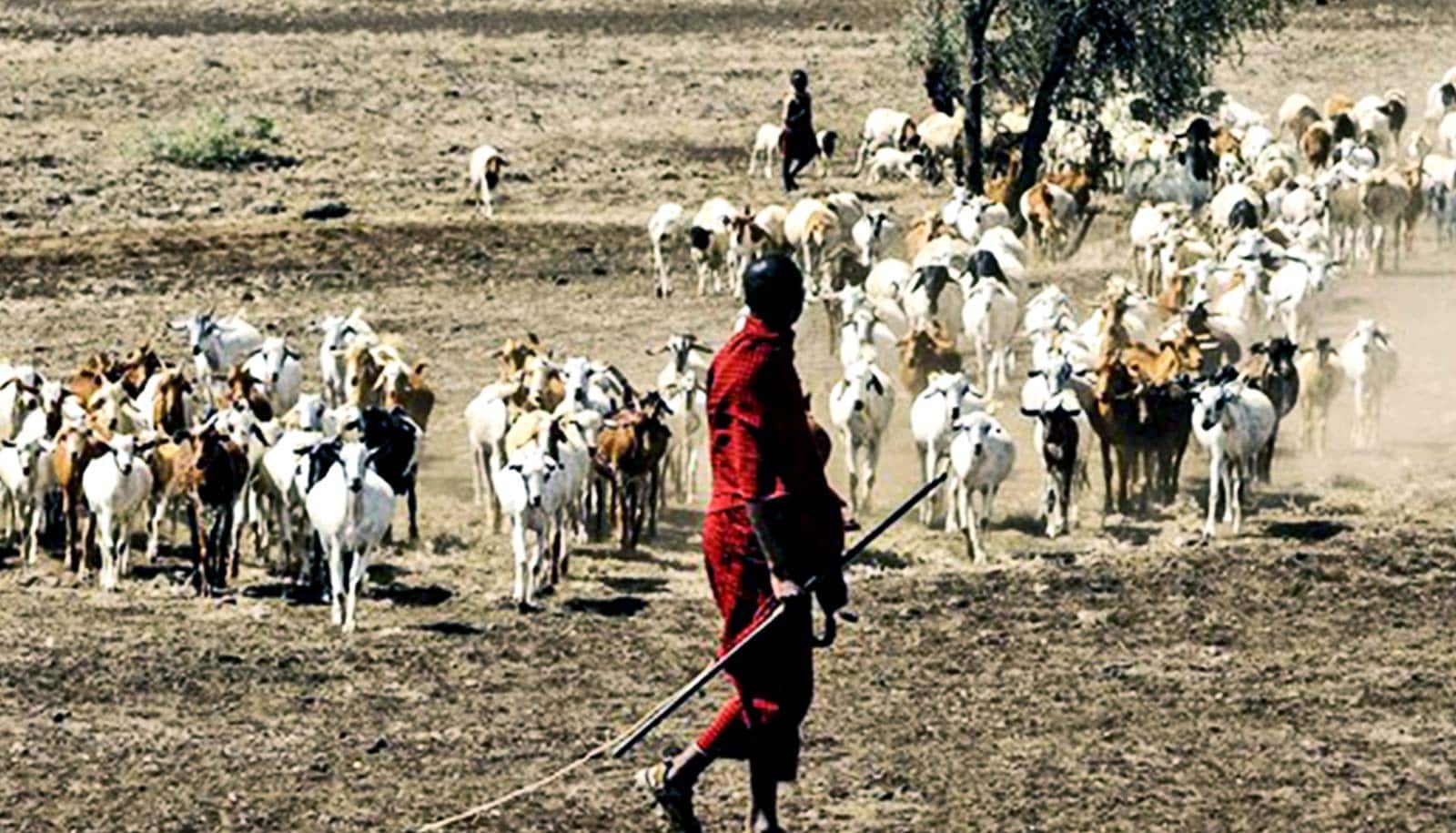

When livestock are the sole source of an owner’s livelihood, they are more likely to become infected with sheep and goat plague virus than when agriculture is part of the mix, a study in Tanzania shows.

Additionally, the study finds that the presence of cattle may affect infection risk, even though they are not typically considered important hosts for the virus, sheep and goat plague virus (PPRV), a widespread and often fatal disease.

“About 330 million people worldwide rely on sheep and goats for their livelihood, so understanding how major livestock diseases spread is critical,” says Catherine Herzog, an epidemiologist and graduate student at Penn State, and first author of the paper, which appears in Epidemiology and Infection.

“Peste des petits ruminants virus (PPRV), also known as sheep and goat plague virus, has been reported in over 70 countries in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, threatening about 80% of the world’s population of sheep and goats. In this study, we provide an up-to-date look at the prevalence of PPRV in northern Tanzania and explore factors that affect how the disease is transmitted.”

PPRV typically kills 50–80% of the sheep and goats it infects. Those that survive contain antibodies in their blood that recognize the virus and prevent future infection. Researchers use the antibodies as an indicator of past infection.

Nannies and ewes

For the new study, researchers surveyed livestock across villages in northern Tanzania for evidence of past infection, comparing rates in herds from pastoral villages, where people rely almost solely on livestock, and from agropastoral villages, where people rely on a mix of livestock and agriculture.

“According to our models, herds from pastoral villages had 3.8 times the risk of becoming infected and developing detectable antibodies compared to those from agropastoral villages,” Herzog says. “If you look only at herds of sheep or only at herds of goats instead of mixed-species herds, that risk increases to 9.4 or 9.5 times higher, respectively, for pastoral systems when compared to agropastoral systems.”

Female sheep and goats also had 1.5 times higher risk of becoming infected than males. Understanding prevalence and infection risk could improve the researcher’s ability to predict how the disease will spread and to refine management techniques to minimize disease risk.

“Next we plan to investigate which aspects of the livestock management system within a pastoral herd may be driving this increased risk,” says coauthor Ottar Bjørnstad, a professor of entomology and biology, who led the research team. “For example, herd size, herd age structure, contact rates among livestock and wildlife, and access to veterinary service may all play a role in infection risk. Knowing which animals are at greater risk of infection may affect how we allocate resources to manage prevention strategies.”

What about cattle?

Although researchers generally consider PPRV a sheep and goat virus, they also included cattle in their surveys and analysis.

“Cattle are often managed alongside sheep and goats and can become infected, although it is unclear if cattle can transmit the disease,” Herzog says. “We found that the rate at which animals become infected—force of infection—was related between sheep and cattle and between goats and cattle. This is consistent with the idea that cattle play a role in transmission to sheep and goats, or, alternatively, that an unknown external factor is affecting transmission in each species in a similar way.”

“To further explore the role of cattle in transmission, we plan to perform experimental transmission trials with all three species with our collaborators in Ethiopia, who also work with us on bovine tuberculosis projects,” says coauthor Vivek Kapur, associate director for strategic initiatives at the Huck Institute of the Life Sciences and professor of microbiology and infectious disease. “Understanding if cattle can transmit to sheep or goats ahead of the upcoming global eradication campaign is a top priority.”

Researchers consider PPRV an attractive target for eradication due to its socio-economic importance and the availability of a vaccine, which provides protection for sheep and goats from the disease for up to 3 years.

“PPRV is not too unlike rinderpest in cattle—one of only two viruses that we have completely eradicated from the planet, thanks in part to good vaccines,” says coauthor Peter Hudson, a professor of biology. “But sheep and goats live shorter lives than cattle, and there are more of them, so it can be a challenge for herd owners to keep up with vaccination. We hope our work will clarify the ecological mechanisms driving PPRV transmission, allowing us to improve vaccination accessibility for at-risk herds and optimize other prevention strategies.”

Additional coauthors are from Penn State, Washington State, the University of Glasgow, Scottish Rural College, and the Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation funded the work.

Source: Penn State