A new effort to compile better data on rural public health could help address the startling health gaps between people in rural and urban areas.

In Washington, for instance, rural residents are one-third more likely to die from intentional self-harm or 13% more likely to die from heart disease.

While statistics like these help guide public health policy and spending, they can hide even greater health disparities within those rural communities, says lead author Betty Bekemeier, director of the School of Public Health’s Northwest Center for Public Health Practice and a professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Washington.

“Populations in rural areas already have suffered disproportionately from a lot of negative health outcomes,” she says. “Then on top of that, they lack the data, capacity, and infrastructure to understand and better address those problems.”

Yet, some of the data rural public health officials need to better serve their communities exists but is hard to access and use. So, what gives?

Including everyone

To find out, Bekemeier and her colleagues at the Northwest Center embarked on the SHARE-NW project: a five-year effort to identify, gather, and visualize data in four Northwest states to help rural communities more effectively address health disparities and achieve health equity.

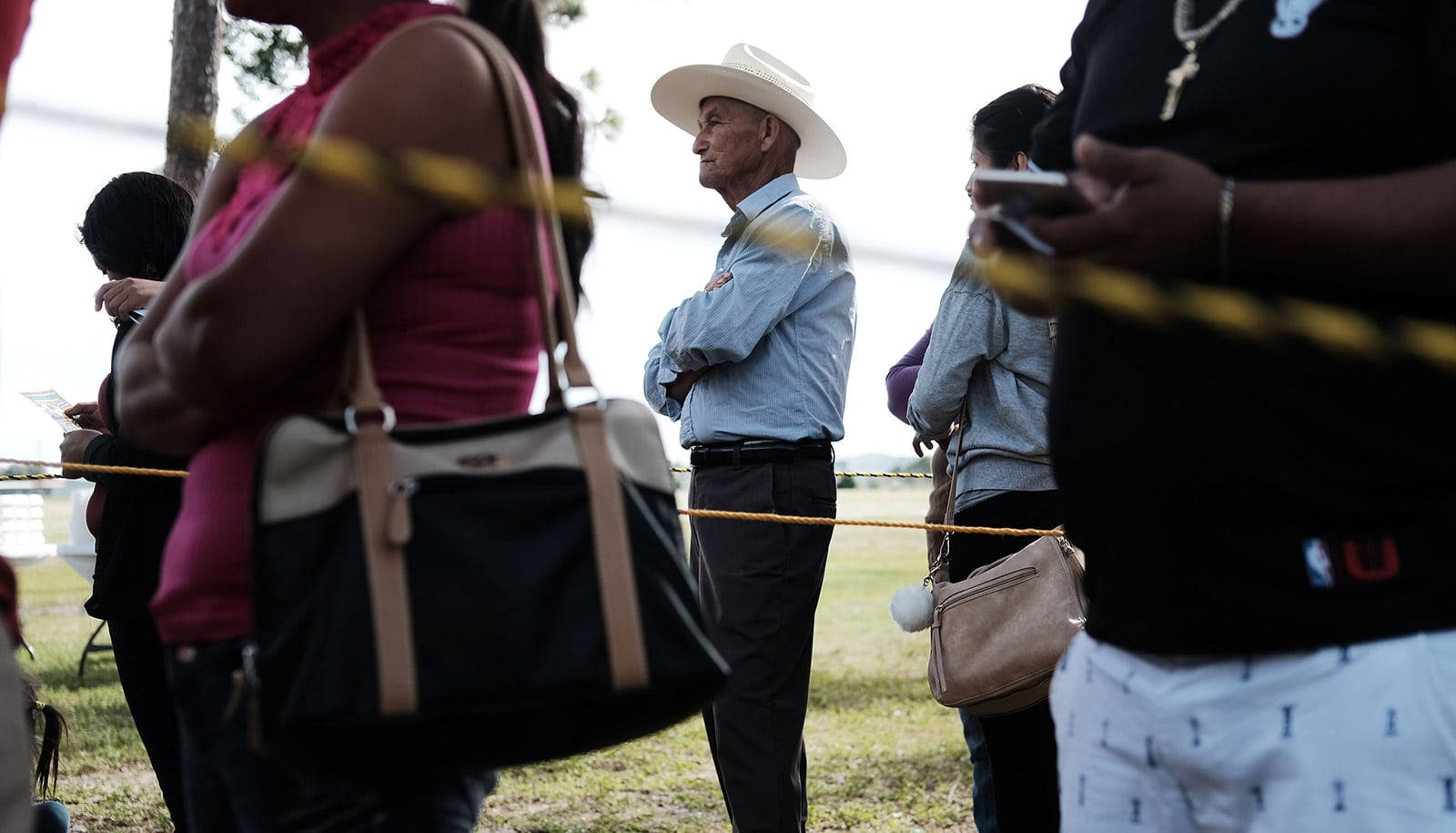

“Rural communities in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska face high poverty and are home to large populations of Alaska Native, Native American, Latino, and other residents who are often marginalized and impacted by health disparities,” the SHARE-NW website explains.

The SHARE-NW project is currently in its third year. The results of the group’s survey of rural leaders appear in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

The researchers conducted phone interviews in 2018 with officials in the four Northwest states, including staff from the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, the Panhandle Health District in Idaho, the Crook County Health Department in Oregon, the Wahkiakum County Health Department in Washington, and 21 other rural health organizations.

“In our study with rural public health system leaders, we identified barriers to using data, such as 1) lack of easy access to timely data, 2) data quality issues specific to rural and tribal communities, and 3) the inability for rural leaders to use those data,” write the study authors.

“You may have a very seemingly homogenous population on the face of it,” says Bekemeier. “But you have small population groups that are very disproportionately impacted by certain issues, and leaders in those communities may not be aware that these problems exist, let alone how deeply individuals are affected.”

For instance, one agency told the researchers: “What immediately comes to mind is our migrant farmworker community, especially with their language barriers and their temporary status in our community… It’s really hard to get the data to know who we’re looking at…”

A better database for rural public health

To address this problem, SHARE-NW is building a readily accessible database and the related visualizations so local health officials can more easily talk about the makeup of their communities, identify local needs, and foster data-supported decisions.

“If you have data, you can talk about what the issues are that need to be prioritized,” Bekemeier explains. “Now, we’re focusing on community-specific data for six priority areas that were common across their community health assessments.”

Those areas are:

- obesity, including physical activity and nutrition/food access;

- diabetes;

- tobacco;

- mental health, including suicide and substance abuse;

- violence and injury; and

- oral health, including access to dental care.

“We’re doing this with them,” she says of the rural health leaders. One of the key elements for creating this robust data and tool set is local participation in not only using the data, but also adding to it from their own local research.

“SHARE-NW is all about building community capacity and bringing information to where it is so deeply needed so that data-driven and community-engaged decisions can be made that will directly affect population-level health disparities and build health equity,” she says.

Source: Jake Ellison for University of Washington