Asian tiger mosquitoes at the northern limit of their current range are using time-capsule-like eggs to survive cold conditions than those of their native territory, researchers report.

When the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) arrived in the United States in the 1980s, it took the invasive blood-sucker only one year to spread from Houston to St. Louis.

The northern mosquitoes have adapted to colder winters, compared with their southern counterparts. This new evidence of rapid local adaptation could have implications for efforts to control the spread of this invasive species, which is considered a “competent vector” of numerous pathogens that are relevant to humans, including Zika, chikungunya, and dengue viruses.

“This all happened within a period of 30 years,” says first author Kim Medley, director of Tyson Research Center at Washington University in St. Louis. “This disease vector has evolved rapidly to adapt to the United States. The fact that this has occurred at a range limit may suggest that there is potential for the species to continue to creep farther northward.”

Waiting to hatch

Mosquitoes respond to the shortening days signaling winter’s onset by laying diapause eggs—literally, delayed development eggs. These special eggs contain a fertilized embryo that’s in a state of almost-hibernation and has a very slow metabolism. The result is almost like a mosquito time capsule.

The ability to produce eggs that can wait to hatch is not something new. This technique helps mosquitoes survive the winter cold, but it works for dry conditions as well. All mosquitoes lay their eggs in or near standing water, and the larvae need to hatch into standing water. But they can survive getting dried out in between.

Still, diapause eggs are different from regular eggs. Previous research had showed that northern mosquitoes lay more diapause eggs than their southern cousins. What researchers didn’t know was how these eggs actually perform in the conditions in which they’re prepped to perform.

Asian tiger mosquitoes in the winter

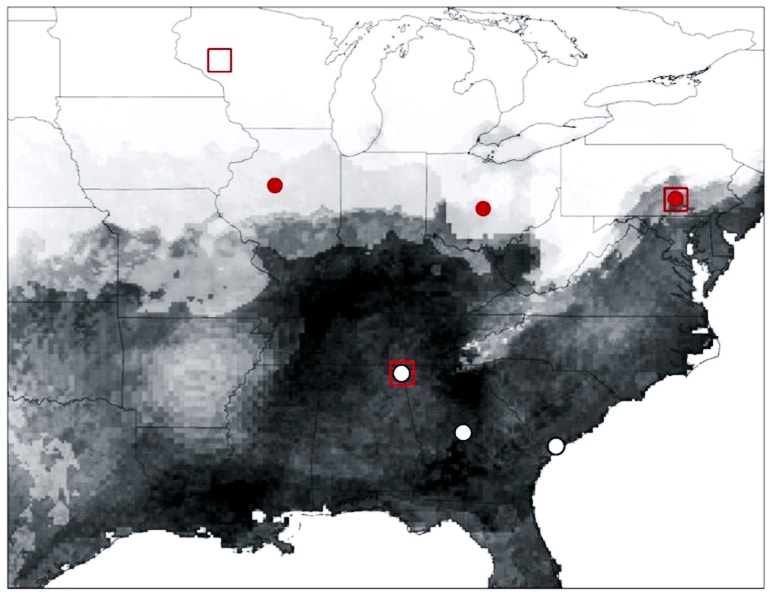

For this new field experiment, the researchers collected live mosquito eggs and larvae from cities near the center of the habitat they’ve invaded (Huntsville, Alabama; Macon, Georgia; Beaufort, South Carolina) and also from the approximate northern edge of their US range (Peoria, Illinois; Columbus, Ohio; and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) The researchers hatched and raised these mosquitoes and their subsequent generations in batches in the laboratory.

Then it was time to get cold. The researchers exposed the mosquitoes to shortened periods of light to signal the onset of winter. They collected the diapause eggs that the mosquitoes produced, then dispatched batches of eggs to endure real winters in four different locations: in field sites at the northern edge and core of their current range; in a climate-controlled laboratory site that represented the “optimal” winter conditions in the mosquitoes’ home territory in Japan; and in a far-north site in Wisconsin, clearly outside of the mosquitoes’ current established range.

After that real winter passed, the researchers brought the eggs back into the lab and hatched them out.

“We counted all of the eggs to see how many survived the winter in all of these locations,” Medley says. “What we learned was that the northern mosquitoes’ diapause eggs survived northern winters significantly better than the southern mosquitoes’ eggs did.

“Everybody did OK in the southern range winter,” she says. “They performed about the same.” The same was true for those in the chamber with the optimal conditions. As for Wisconsin?

“Nobody survived that Wisconsin winter,” Medley says.

The edge of survivability

While the Wisconsin conditions are too harsh for these mosquitoes—at least for now—Medley is particularly interested in the changes that she is observing at the very edge of what is survivable.

“These northern mosquitoes are producing a lot more diapause eggs,” Medley says. “Now we know that these eggs also do a lot better in the winter.”

What Medley and her team learned is important not just for this species but for ecologists studying how animals adapt to new conditions and push the boundaries of their historic ranges.

“Based on theory, we expect that populations at range limits will be small, they will be fragmented, and that they will be low in genetic diversity,” she says. “It’s thought that these populations will not have the demographic and genetic robustness to adapt, so they remain at this state of maladaptation. That may not be the case with this species,” Medley says.

The work appears in the Journal of Applied Ecology.