When it comes to garnering support for environmental causes, talking about the consequences of a loss works better than talking about the benefits of a gain, a new study shows.

One of the difficulties in environmental management is garnering public support for a course of action designed to address a particular problem. Researchers find that the way you frame a project can make a big difference in how the public responds to it.

The study in PLOS ONE explores “which types of benefits or losses environmental managers should communicate and how to frame those attributes to achieve greater public support.”

The study, which surveyed more than 1,000 Californians, focused on invasive species—a subject that, unlike climate change, has not been politicized, the researchers say.

The authors suspected that, as a politically neutral issue, invasive species would allow them to test different messages based on either preventing losses or facilitating gains.

Prospect theory and environmental causes

How people react to these messages has roots in prospect theory, “which proposes that people are more responsive to potential losses than equivalent potential gains—the psychological effect of losing $100 is greater than the positive effect of gaining $100.”

“We didn’t really know whether that could be applied equivalently for something that you don’t actually own—this public good,” says Alex DeGolia, a 2017 PhD graduate in political science from theUniversity of California, Santa Barbara who is now deputy director of the Catena Foundation in Colorado.

What’s more, he says, because of the politics surrounding climate change, merely talking about the environment signals political affiliation, making people less likely to change opinions.

“They interpret information through an already politicized lens,” DeGolia says, “and they’re less open to evaluate that information from a less-biased perspective.”

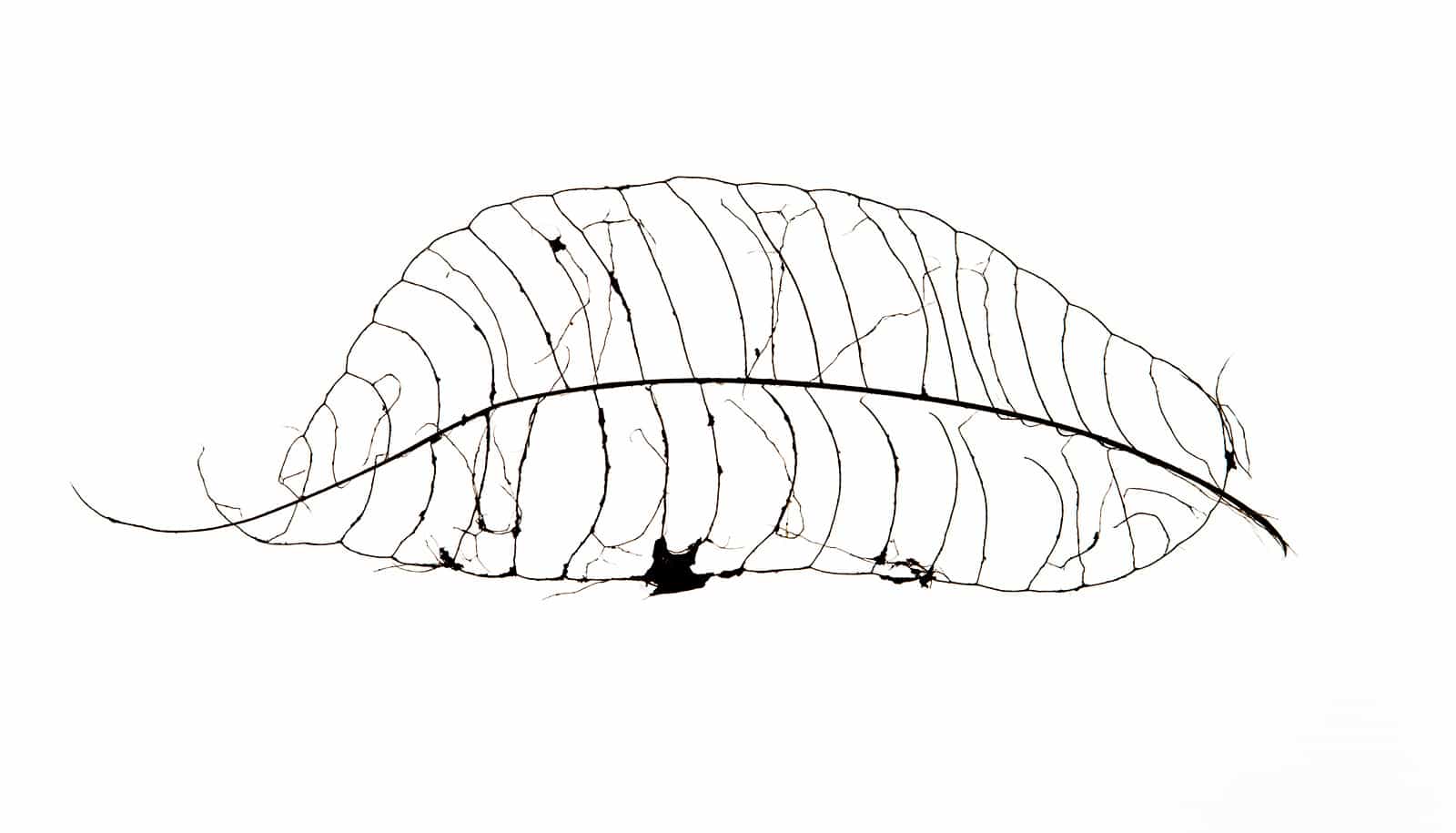

But the researchers hypothesized that might not be the case with a less-politicized issue like invasive species. So they created press releases for a fictional program to manage invasive wild pigs that mirrored those of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW).

The releases centered on “framing, which highlights information that connects to people’s core concerns or beliefs,” the authors write. “Frames contextualize policy issues, making them more immediately accessible and more relevant and understandable for the public.”

In addition to a control release that didn’t mention losses or gains, they drafted four other releases; two referenced potential gains and two referenced averted losses. Of those, one referenced economic gains vs. losses, while the other referenced ecological gains vs. losses.

Skip the politics

While the researchers expected an economic argument would be more effective with conservatives and liberals would be more responsive to an environmental appeal, they were in for a surprise.

It turned out political moderates and conservatives both responded positively to an environmental argument when the issue didn’t include political baggage.

Given that, “maybe you don’t have to be as precise in terms of who you’re going to talk to,” DeGolia says.

“You don’t have to necessarily highlight the economic benefits to conservatives and environmental benefits to liberals if it’s not really closely aligned with political identity. Instead, maybe you can just talk about the environmental benefits of a program like this and expect that that is going to elicit fairly positive responses across the board.”

It’s often assumed that “people don’t actually really care that much about the environment for its own sake. They care about their pocketbook, DeGolia says. “So when we talk about climate we should be talking about our jobs.”

This work showed that managers don’t necessarily need to focus on economic benefits, but can emphasize the environmental benefits of programs in areas less politicized than climate. And talking about avoiding losses works better than talking about what implementing the project could gain.

“People were most supportive when we highlighted that the program would avoid further habitat and species loss,” says Sarah Anderson, an associate professor of environmental politics. “Managers in less-politicized areas like water management and endangered species management can take a lesson from this research in how to communicate to the public about their management strategies: talk about avoiding ecological problems in the future.”

The H. William Kuni Fellowship at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management funded the work.

Source: UC Santa Barbara