A new method can turn proteins into never-ending patterns called fractals, report researchers.

They say the method could help engineer human tissues or create a filter for tainted water.

“Biomolecular engineers have been working on modifying the building blocks of life—proteins, DNA, and lipids—to mimic nature and form interesting and useful shapes and structures,” says senior author Sagar D. Khare, an associate professor in the chemistry and chemical biology department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. “Our team developed a framework for engineering existing proteins into fractal shapes.”

In nature, building blocks such as protein molecules are assembled into larger structures for specific purposes. A classic example is collagen, which forms connective tissue in our bodies and is strong and flexible because of how it is organized. Tiny protein molecules assemble to form structures that can scale up and be as long as tendons. Assemblies of natural proteins are also dynamic, forming and dissolving in response to stimuli.

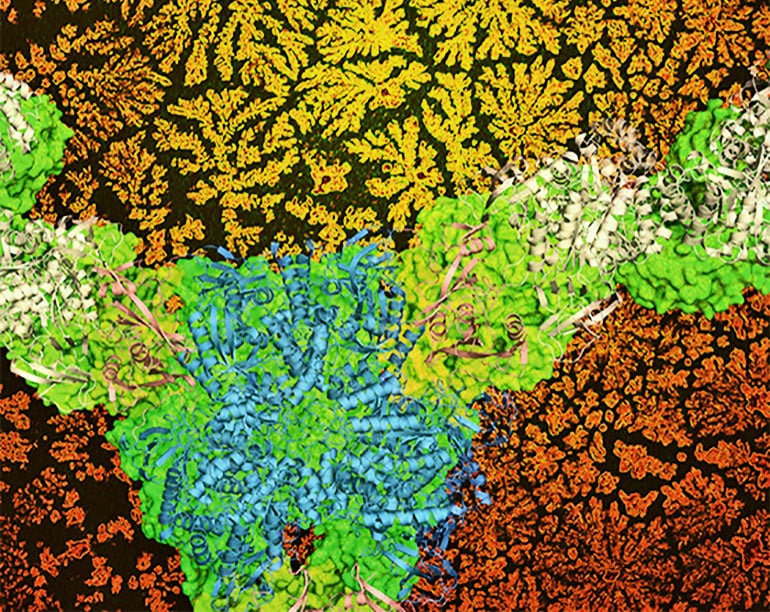

The research team developed a technique for assembling proteins into fractal, or geometric, shapes that repeat over and over. The team used protein engineering software to design proteins that bind to each other, so they form a fractal, tree-like shape in response to a biological stimulus, such as in a cell, tissue, or organism. They can also manipulate the dimensions of the shapes, so they resemble flowers, trees, or snowflakes, which researchers visualize using special microscopy techniques.

These techniques could lead to new technologies such as a filter for bioremediation, which uses biological molecules to remove herbicides from tainted water, or synthetic matrices to help study human disease, or aid tissue engineering to restore, improve, or preserve damaged tissues or organs.

The next steps are to further develop the technology and expand the range of proteins that form fractal shapes as well as use different stimuli, such as chemicals and light. The scientists also want to study how fractal shapes form in greater detail, so they could gain greater control over the process and the shapes and sizes of designer biomaterials.

The new study appears in the journal Nature Chemistry. Coauthors are from the Baylor College of Medicine and the University of Minnesota.

Source: Rutgers University