Custom-made artificial heart valves made with 3D printing could help meet an aging population’s growing demand for replacement heart valves, according to new research.

The human heart has four chambers, each equipped with a valve to ensure blood flow in one direction only. If any of the heart valves are leaking, narrowed or distended (or even ruptured), the blood runs back into the atria or ventricles, putting the entire heart under severe strain. In the worst case, this can lead to arrhythmia or even heart failure.

Depending on the severity of the defect, artificial heart valves can remedy the problem. Over the next few decades, demand for this type of surgery is likely to soar in many parts of the world due to the aging population, lack of physical exercise, and poor diet. It is estimated that around 850,000 people will require artificial heart valves in 2050. Researchers have been looking for an alternative to the replacement heart valves currently in use.

Unlike conventional heart valves, the silicone heart valve can be tailored more precisely to the patient, as the researchers first determine the individual shape and size of the leaky heart valve using computer tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. This makes it possible to print a heart valve that fits the patient’s heart chamber perfectly.

The researchers use the images to create a digital model and a computer simulation to calculate in advance the forces acting on the implant and its potential deformation. The material used is also compatible with the human body, while the blood flow through the artificial heart valve is as good as with conventional replacement valves.

Heart surgeons have traditionally used implants that consist either of hard polymers or animal tissue (from cows or pigs) combined with metal frames. To prevent the body rejecting these implants, patients have to take life-long immunosuppressants or anticoagulants, which have significant undesirable side effects.

Easier, cheaper, better

In addition, conventional replacement valves have a very rigid geometric shape, making it challenging for surgeons to ensure a tight seal between the new valves and the cardiac tissue.

“The replacement valves currently used are circular, but do not exactly match the shape of the aorta, which is different for each patient,” says co-lead author Manuel Schaffner, a former doctoral student of André Studart, professor for complex materials at ETH Zurich. On top of that, manufacturing artificial heart valves is both expensive and time-consuming.

The new type of silicone heart valves gets around this problem. It only takes about an hour and a half for researchers to produce such a valve with a 3D printer. By contrast, it takes several working days to make an artificial heart valve by hand from bovine material. Production with 3D printers could also speed up: a battery of printers could, for example, produce dozens or even hundreds of valves every day.

Making new heart valves

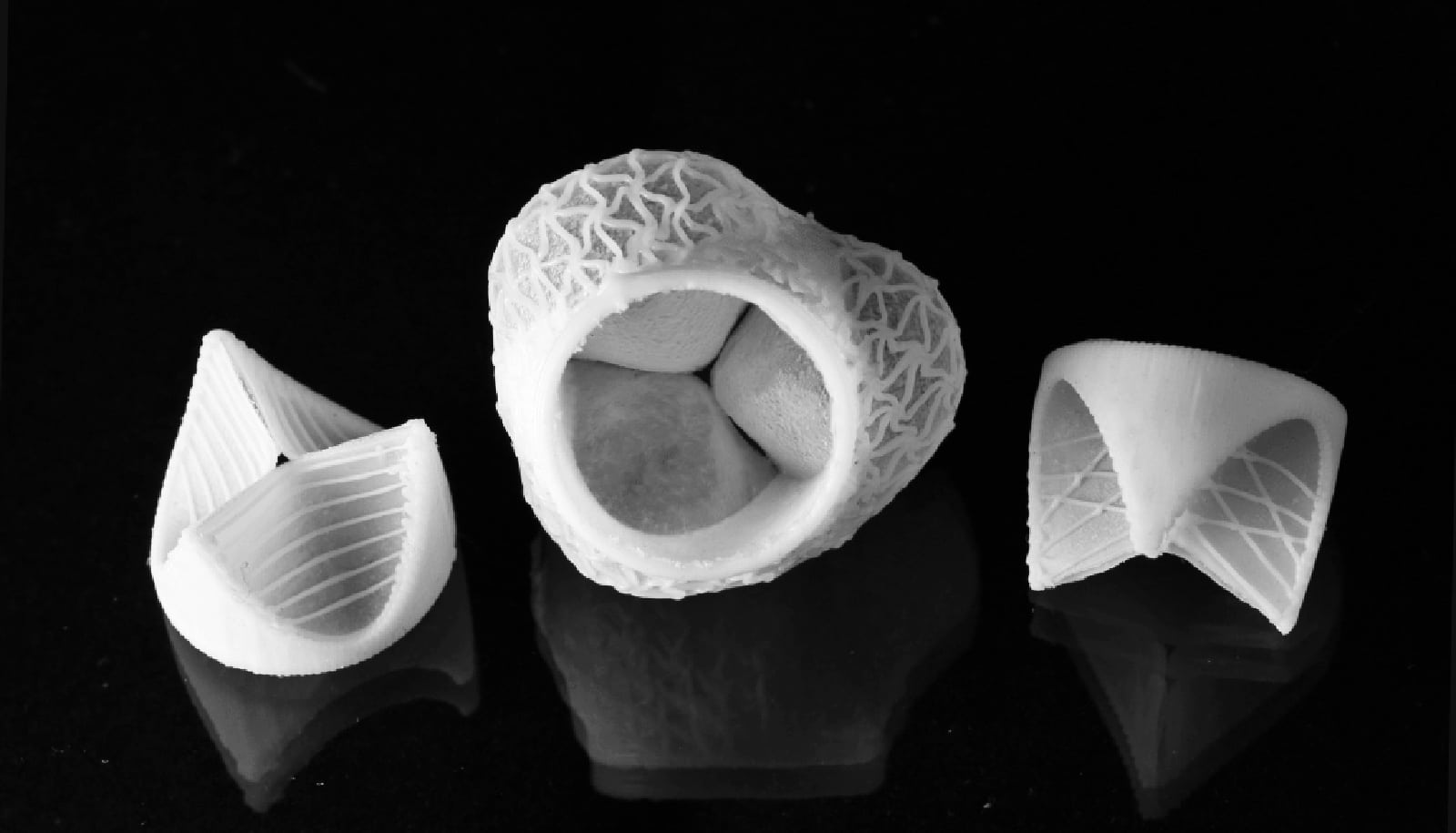

First, the scientists create a negative impression of the valve. They spray silicone ink onto this impression in the shape of a three-pointed crown, which forms the valve’s thin flaps.

In the next step, an extrusion printer deposits tough silicone paste to print specific patterns of thin threads on their surface. These correspond to collagen fibers that pass through natural heart valves. The silicone threads reinforce the valve flap and extend the life of the replacement valve. The researcher print the root of the blood vessel connected to the heart valve using the same procedure and at the end they cover it with a net-shaped stent, which is necessary for connecting the silicone valve replacement to the patient’s cardiovascular system.

Initial tests have produced very promising results for the new valve’s function. The material scientists’ goal is to extend the life of these replacement valves to 10-15 years. This is how long current models last in patients before they need to be exchanged.

“It would be marvelous if we could one day produce heart valves that last an entire lifetime and possibly even grow along with the patient, so that they could also be implanted in young people as well,” says Schaffner.

However, it will still take at least 10 years before the new artificial heart valves come into clinical use, as they first have to go through exhaustive clinical trials.

Co-lead author Fergal Coulter, a postdoc in Studart’s group who developed the 3D printers that produce the heart valves, is currently working on the further development of the silicone heart valve. “These experiments are needed to make sure that the technology has any chance at all of being used in human patients,” he stresses.

Coulter is also continuing to experiment with new materials that could extend the life of the heart valves.

However, either an industrial partner or possibly a spin-off is needed to make the heart valve commercially available on the market. “As a research group, we are unfortunately unable to provide a seamless offering from the first experiment to the first application in the human body,” Schaffner emphasizes.

The research appears in the journal Matter. Additional researchers from ETH Zurich and the South African company SAT contributed to the work.

Source: ETH Zurich