A majority of people who use opioid drugs would willingly use safe consumption spaces, a new study reports.

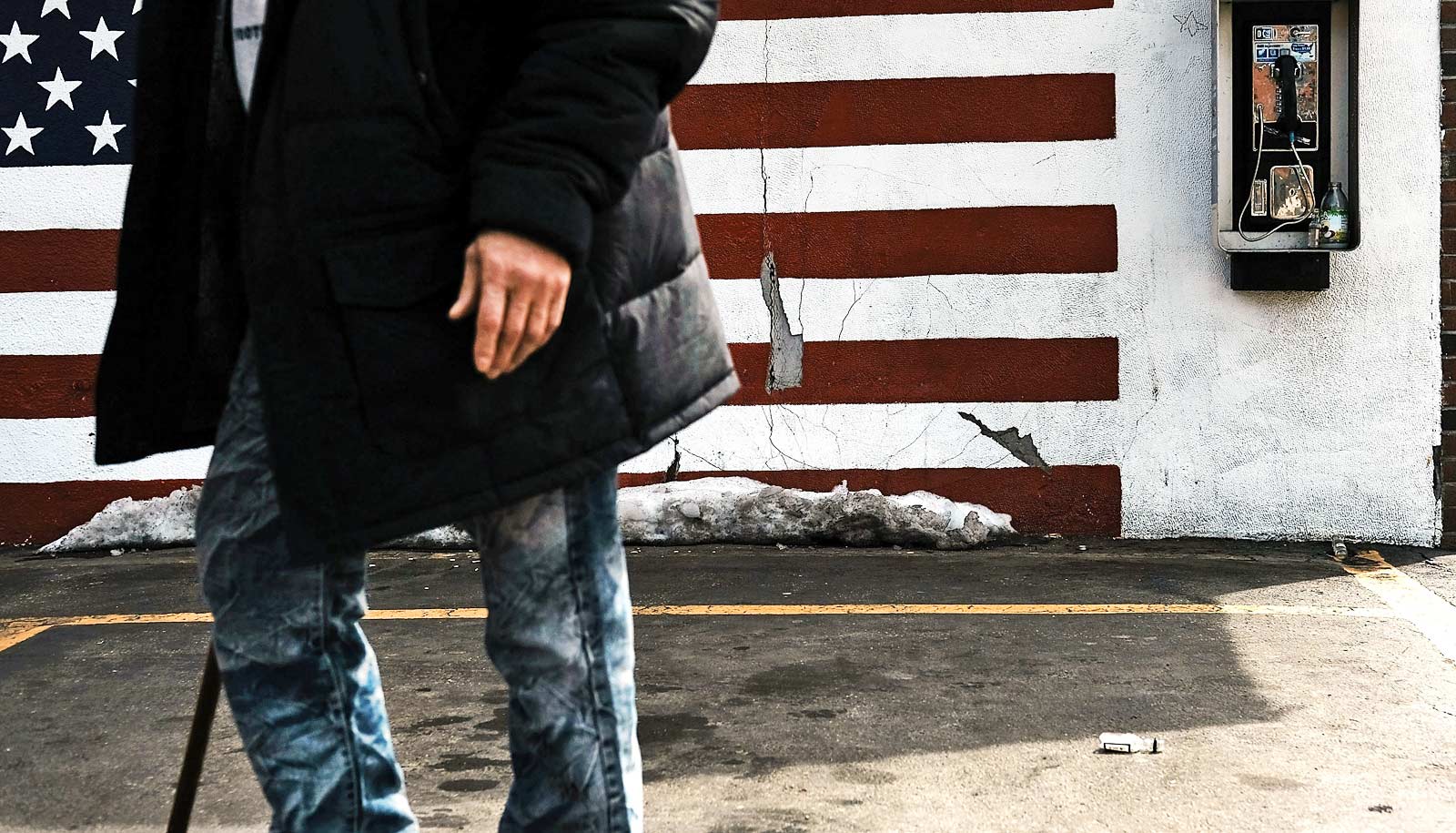

The United States currently has no such facilities where users could receive sterile syringes and, in case of overdose, medical support.

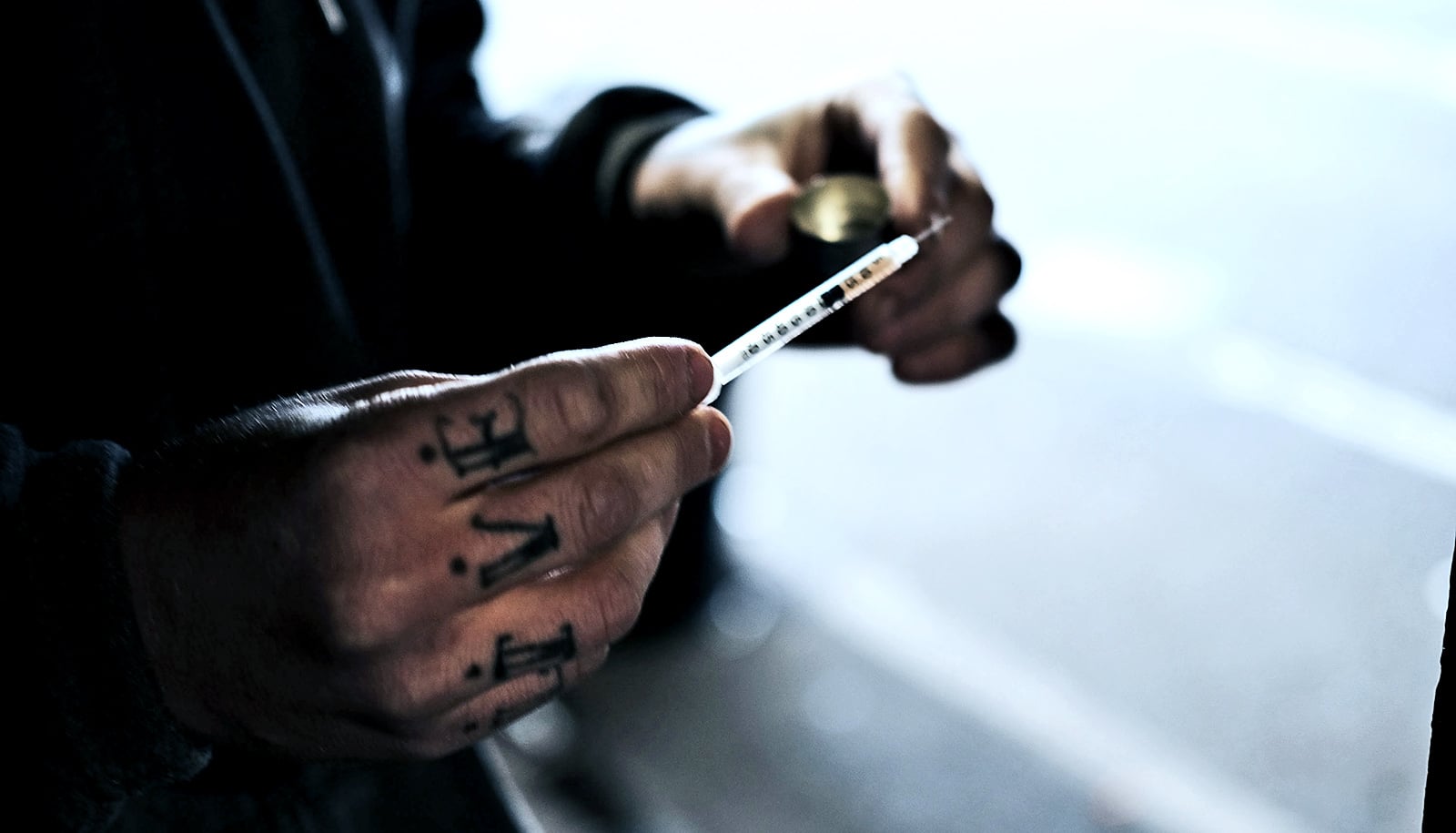

Researchers surveyed more than 300 people who use heroin, fentanyl, and illicit opioid pills in Baltimore, Boston, and Providence, Rhode Island. About 77 percent of participants reported a willingness to use safe consumption spaces. Canada, Australia, and other countries have set up and evaluated these types of sites.

“This study is an important first step in exploration of safe consumption spaces in these three cities,” says Traci Green, an associate professor of emergency medicine and epidemiology at Brown University and Boston University and senior author of the paper in the Journal of Urban Health.

“Rigorous and measured scientific approaches to new innovations like safe consumption spaces can help inform policy and better equip public health responses to the opioid crisis.”

Safe consumption spaces, also called safe injection facilities and overdose prevention sites, are a proven method to reduce the harms stemming from opioid use disorders, according to the study. Countries outside the US have used them for more than 30 years.

However, there are no legal safe consumption spaces in the US due in part to a federal law that creates a serious criminal liability for anyone knowingly connected with a property for illegal drug use, researchers say.

Policymakers in Rhode Island and a few other states are pursuing legislation to make safe consumption spaces viable options for stemming the ongoing opioid overdose epidemic.

The researchers surveyed 326 people in Providence, Boston, and Baltimore who said they had used opioids non-medically in the past 30 days. Of those surveyed, 68 percent of the Providence participants, 84 percent of the Boston participants, and 78 percent of the Baltimore participants said they were willing to use a safe consumption space.

Willingness to use these spaces was even higher—84 percent—among people who primarily used opioids in public spaces such as streets, parks, and abandoned buildings, according to the study.

When asked what could hinder use of a safe space, 38 percent said fear of arrest and 36 percent pointed to privacy concerns.

Of the people surveyed, almost 70 percent were homeless, and 60 percent reported habitually using drugs in public or semi-public places. More than a third reported having experienced an overdose in the past six months, and 73 percent reported recent use of a drug they suspected had contained fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is much more potent than heroin and implicated in an increasing number of fatal overdoses.

“On the whole, we found a strong willingness to use safe consumption spaces,” says lead author Ju Nyeong Park, an assistant scientist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “It’s encouraging because even though these are people engaging in very high-risk behaviors in very different contexts within these three cities, they were willing to use this harm-reduction intervention.”

Additional authors are from Brown and Johns Hopkins. The Bloomberg American Health Initiative and the National Institutes of Health supported the work.

Source: Brown University