A new effort to map the most abundant of the symbiotic relationships among trees, fungi, and bacteria—involving more than 1.1 million forest sites and 28,000 tree species—reveals factors that determine where different types of symbionts will flourish.

In and around the tangled roots of the forest floor, fungi and bacteria grow with trees, exchanging nutrients for carbon in a vast, global marketplace.

Mapping these relationships could help scientists understand how symbiotic partnerships structure the world’s forests and how a warming climate could affect them.

“Our models predict massive changes to the symbiotic state of the world’s forests—changes that could affect the kind of climate your grandchildren are going to live in.”

A team of over 200 scientists to generate these maps, which revealed a new biological rule, which the team named Read’s Rule after pioneer in symbiosis research Sir David Read.

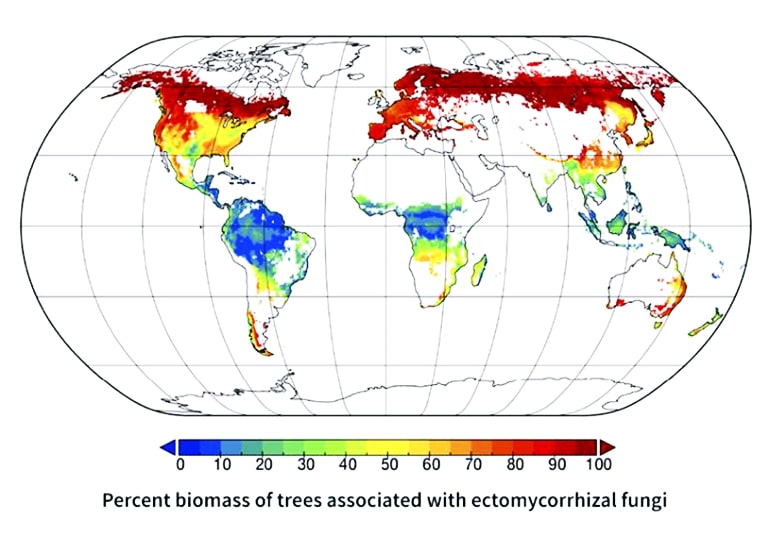

In one example of how they could apply this research, the researchers used their map to predict how symbioses might change by 2070 if carbon emissions continue unabated. This scenario resulted in a 10 percent reduction in the biomass of tree species that associate with a type of fungi found primarily in cooler regions.

The researchers caution that such a loss could lead to more carbon in the atmosphere because these fungi tend to increase the amount of carbon stored in soil.

“There’s only so many different symbiotic types and we’re showing that they obey clear rules,” says lead author Brian Steidinger, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. “Our models predict massive changes to the symbiotic state of the world’s forests—changes that could affect the kind of climate your grandchildren are going to live in.”

Hidden connections

Hidden to most observers, these inter-kingdom collaborations between microbes and trees are highly diverse.

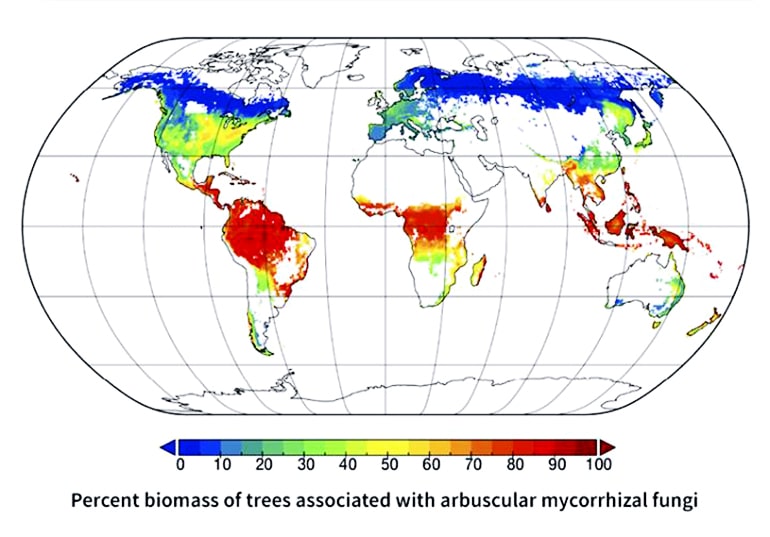

The researchers focused on mapping three of the most common types of symbioses: arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, ectomycorrhizal fungi, and nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Each of these types encompasses thousands of species of fungi or bacteria that form unique partnerships with different tree species.

Thirty years ago, Read drew maps by hand of where he thought different symbiotic fungi might reside, based on the nutrients they provide. Ectomycorrhizal fungi feed trees nitrogen directly from organic matter—like decaying leaves—so, he proposed, they would be more successful in cooler places where decomposition is slow and leaf litter is abundant.

In contrast, he thought arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi would dominate in the tropics where soil phosphorous limits tree growth. Research by others has added that nitrogen-fixing bacteria seem to grow poorly in cool temperatures.

Testing Read’s ideas had to wait, however, because proof required gathering data from large numbers of trees in diverse parts of the globe. That information became available with the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative, which surveyed forests, woodlands, and savannas from every continent (except Antarctica) and ecosystem on Earth.

“In many cases, as part of these measurements, they essentially gave the tree a hug,”

The team fed the location of 31 million trees from that database along with information about what symbiotic fungi or bacteria most often associates with those species into a learning algorithm that determined how different variables such as climate, soil chemistry, vegetation, and topography seem to influence the prevalence of each symbiosis.

From this, they found that temperature and soil acidity probably limit nitrogen-fixing bacteria, whereas variables that affect decomposition rates—the rate at which organic matter breaks down in the environment—such as temperature and moisture heavily influence the two types of fungal symbioses.

Worldwide patterns

“These are incredibly strong global patterns, as striking as other fundamental global biodiversity patterns out there,” says senior author Kabir Peay, assistant professor of biology. “But before this hard data, knowledge of these patterns was limited to experts in mycorrhizal or nitrogen-fixer ecology, even though it is important to a wide range of ecologists, evolutionary biologists and earth scientists.”

Although the research supported Read’s hypothesis—finding arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in warmer forests and ectomycorrhizal fungi in colder forests—the transitions across biomes from one symbiotic type to another were much more abrupt than expected, based on the gradual changes in variables that affect decomposition.

This supports another hypothesis, the researchers thought: that ectomycorrhizal fungi change their local environment to further reduce decomposition rates.

This feedback loop may help explain why the researchers saw the 10 percent reduction in ectomycorrhizal fungi when they simulated what would happen if carbon emissions continued unabated to 2070. Warming temperatures could force ectomycorrhizal fungi over a climatic tipping point, beyond the range of environments they can alter to their liking.

“There are more than 1.1 million forest plots in the dataset and every one of those was measured by a person on the ground. In many cases, as part of these measurements, they essentially gave the tree a hug,” says Steidinger. “So much effort—hikes, sweat, ticks, long days—is in that map.”

The maps from this study will be made freely available, in hopes of helping other scientists include tree symbionts in their work. In the future, the researchers intend to expand their work beyond forests and to continue trying to understand how climate change affects ecosystems.

The research appears in Nature.

Additional coauthors on this paper are from Stanford, the University of Oxford, the University of Minnesota, Western Sydney University (Australia), Wageningen University and Research (The Netherlands), Wageningen Environmental Research, Universitat de Lleida (Spain), the Forest Science and Technology Centre of Catalonia, Purdue University, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the CIRAD-University of Montpellier (France), Beijing Forestry University, ETH Zürich (Switzerland), and additional members of the GFBI consortium.

Funding for the work came from the Global Forest Biodiversity Database, which represents the work of over 200 independent investigators and their public and private funding agencies.

Source: Stanford University