Differences in fat cells could potentially identify people predisposed to metabolic diseases such as diabetes and fatty liver disease.

The discovery also identifies “fast burning” fat cells that, if unlocked, might help people lose weight.

Previous research has linked overweight or obesity to metabolic disease risk. The new study finds that an individual’s level of risk might depend upon the type of fat they store.

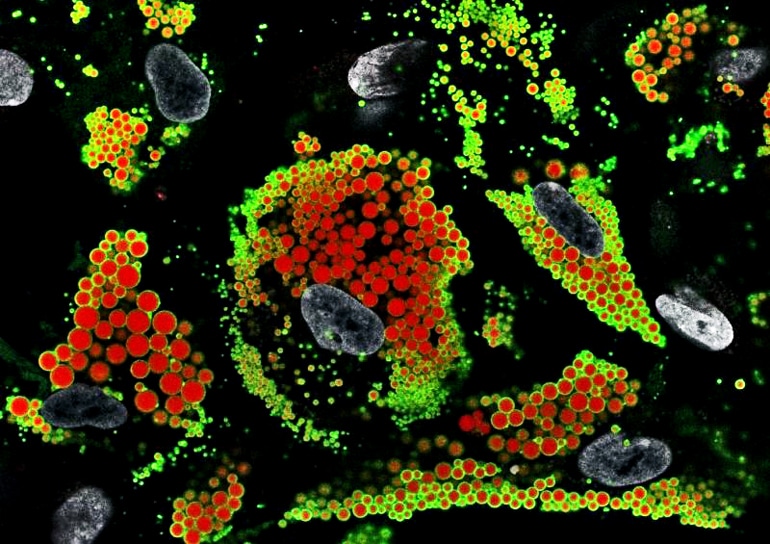

The study took samples from human volunteers and discovered three specific subtypes of precursor cells that went on to become fat cells.

The first released lots of fat into the bloodstream, the second burned energy at a high rate, and the third was “rather benign” and did what a fat cell should normally do, but slowly.

All three cell subtypes were present in fat tissue throughout the body, and not confined to a particular part. All were present in all fat samples. Some people had more of some cell subtypes and less of others.

Senior author Matthew Watt, head of physiology in the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Melbourne, says the results indicate that the makeup of these cells in a person’s body could help to determine their health.

Further research could potentially determine ways to “switch off” the fat releasing cells and “switch on” the fat burning cells.

Watt says the first subtype might increase the risk of fatty deposits around the body and on organs, regardless of whether they were overweight or not, while the second could possibly prevent weight gain. The third was neutral.

While it is early days, he says further research could potentially determine ways to “switch off” the fat releasing cells and “switch on” the fat burning cells. This would involve developing drug therapies and could take at least 10 years.

Watt says that, if scientists can develop them, such treatments could help prevent some illnesses in a less invasive way than bariatric surgery. But they should also involve lifestyle changes.

“Whilst we advocate new discoveries to inform the development of anti-obesity therapies, a healthy lifestyle, including daily activity and reduced food intake, is also important,” he says.

Watt’s team separated different cell types, investigated their genes, and assessed proteins and metabolism. They found three subtypes of fat cells, which are also known as adipocyte progenitor cells.

“The discovery is important because it tells us that not all fat cells are the same and that by understanding the fat subtypes in a human, we might be able to predict their future metabolic health,” Watt says.

While the results indicated certain cell subtypes might increase risk of metabolic disease, Watt says a clinical trial was now needed to accurately answer that question. At this stage it was not practical to routinely test fat composition.

“This requires very detailed and expensive tests,” Watt says. “Until we show a link between certain fat cells and health traits this will not be a useful test.

“We first need to determine whether the number of the fat cell subtypes affects disease development. Then we can work out ways to decrease or increase a certain type of fat cell type to improve health, but again this will require further experimentation.”

The research appears in Cell Reports.

Source: University of Melbourne