Thousands of years before machine learning and self-driving cars became reality, the tales of giant bronze robot Talos, artificial woman Pandora, and their creator, the god Hephaestus, filled the imaginations of people in ancient Greece.

Historians usually trace the idea of automata to the Middle Ages, when humans first invented self-moving devices, but the concept of artificial, lifelike creatures dates to the myths and legends from at least about 2,700 years ago, says Adrienne Mayor, a research scholar in the classics department in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. These ancient myths are the subject of Mayor’s latest book, Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology (Princeton University Press, 2018).

“Our ability to imagine artificial intelligence goes back to the ancient times…”

“Our ability to imagine artificial intelligence goes back to the ancient times,” says Mayor, who is also a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. “Long before technological advances made self-moving devices possible, ideas about creating artificial life and robots were explored in ancient myths.”

Mayor, a historian of science, says that the earliest themes of artificial intelligence, robots, and self-moving objects appear in the work of ancient Greek poets Hesiod and Homer, who were alive sometime between 750 and 650 BCE.

The story of Talos, which Hesiod first mentioned around 700 BCE, offers one of the earliest conceptions of a robot, Mayor says.

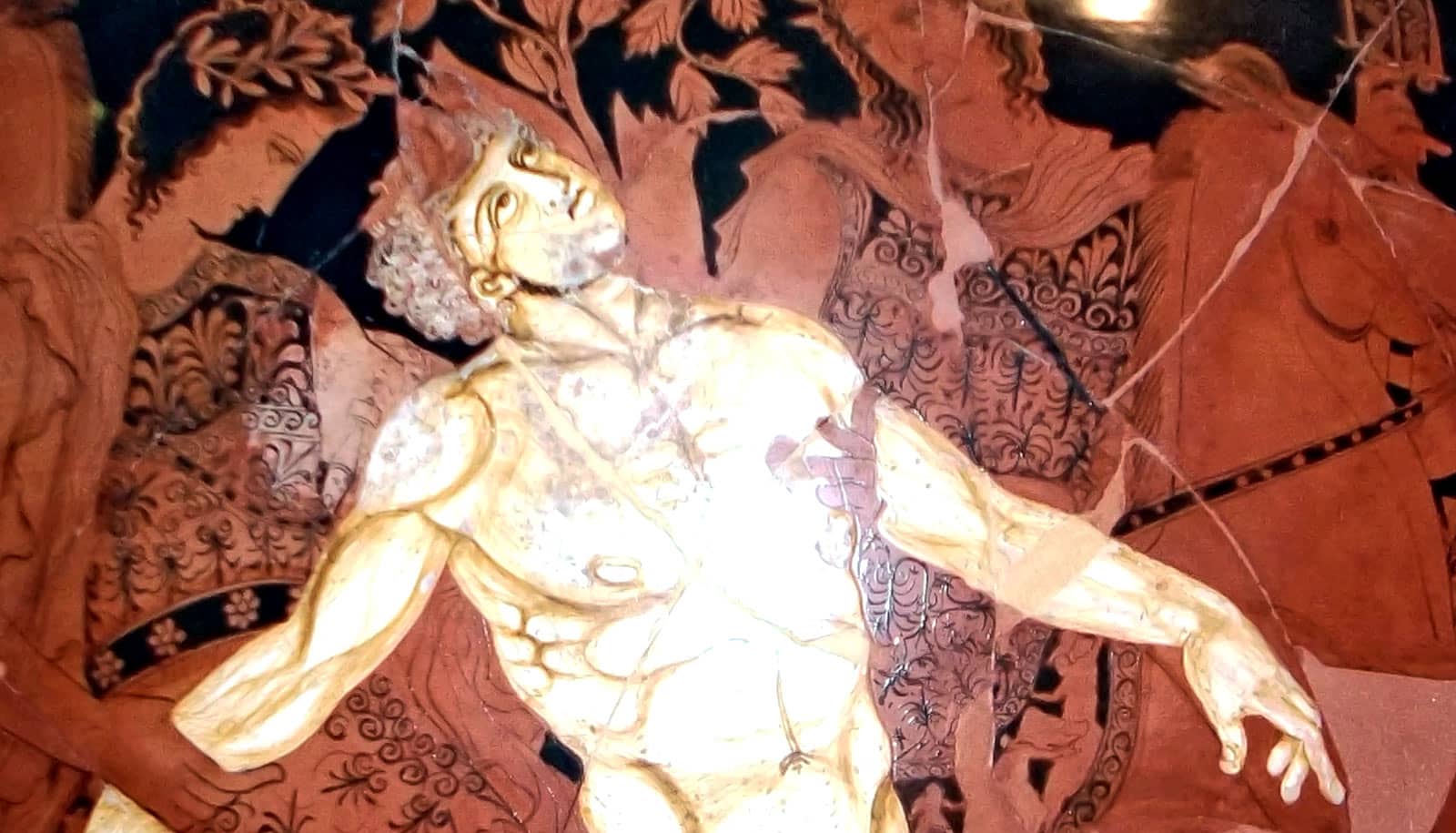

The myth describes Talos as a giant bronze man that Hephaestus, the Greek god of invention and blacksmithing, built. Zeus, the king of Greek gods, commissioned Talos to protect the island of Crete from invaders. He marched around the island three times every day and hurled boulders at approaching enemy ships.

At his core, the giant had a tube running from his head to one of his feet that carried a mysterious life source of the gods the Greeks called ichor. Another ancient text, Argonautica, which dates to the third century BCE, describes how sorceress Medea defeated Talos by removing a bolt at his ankle and letting the ichor fluid flow out, Mayor says.

The myth of Pandora, first described in Hesiod’s Theogony, is another example of a mythical artificial being, Mayor says. Although much later versions of the story portray Pandora as an innocent woman who unknowingly opened a box of evil, Mayor says Hesiod’s original described Pandora as an artificial, evil woman Hephaestus built and Zeus ordered to Earth to punish humans for discovering fire.

“There is a timeless link between imagination and science.”

“It could be argued that Pandora was a kind of AI agent,” Mayor says. “Her only mission was to infiltrate the human world and release her jar of miseries.”

In addition to creating Talos and Pandora, mythical Hephaestus made other self-moving objects, including a set of automated servants, who looked like women but were made of gold, Mayor says. According to Homer’s recounting of the myth, Hephaestus gave these artificial women the gods’ knowledge. Mayor argues that they could be considered an ancient mythical version of artificial intelligence.

The ancient myths that Mayor examined in her research grapple with the moral implications of Hephaestus’ creations.

“Not one of those myths has a good ending once the artificial beings are sent to Earth,” Mayor says. “It’s almost as if the myths say that it’s great to have these artificial things up in heaven used by the gods. But once they interact with humans, we get chaos and destruction.”

Mayor says the myths underscore humanity’s fascination with creating artificial life.

“People have an impulse to imagine things that aren’t possible yet,” Mayor says. “There is a timeless link between imagination and science.”

Source: Stanford University