The extinction of many coral species may be weakening reef systems and siphoning life out of the corals that remain, according to a new study.

In the shallows off Fiji’s Pacific shores, marine researchers assembled groups of corals that were all of the same species, i.e. groups without species diversity. When Cody Clements, a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia Tech and the study’s first author, snorkeled down for the first time to check on them, his eyes instantly told him what his data would later reveal.

“One of the species had entire plots that got wiped out, and they were overgrown with algae,” says Clements. “Rows of corals had tissue that was brown—that was dead tissue. Other tissue had turned white and was in the process of dying.”

Many species vs. one

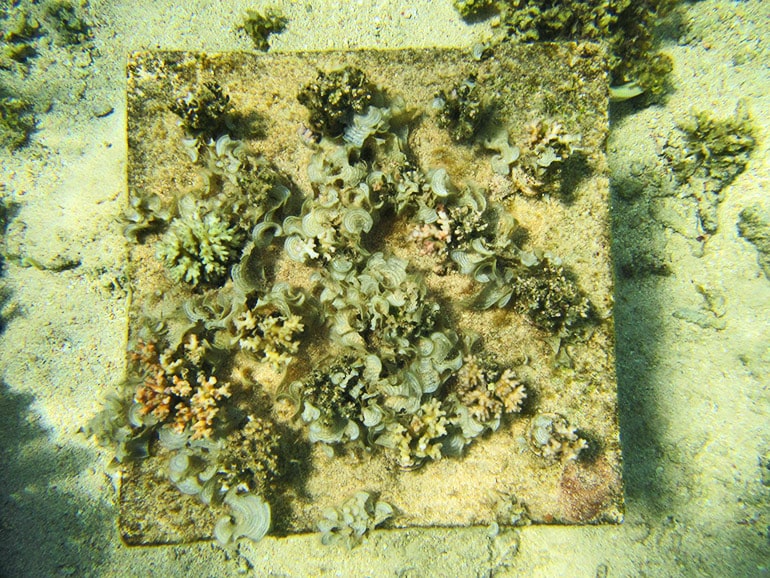

Clements also assembled groups of corals with a mixture of species, i.e. biodiverse groups, for comparison. In total, there were 36 single-species plots, or monocultures. Twelve additional plots contained polycultures that mixed three species.

By the end of the 16-month experiment, monocultures had faired obviously worse. And the study had shown via the measurably healthier growth in polycultures that science can begin to quantify biodiversity’s contribution to coral survival as well as the effects of biodiversity’s disappearance.

“This was a starter experiment to see if we would get an initial result, and we did,” says principal investigator Mark Hay, professor and chair in Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences. “So much reef death over the years has reduced coral species variety and made reefs more homogenous, but science still doesn’t understand enough about how coral biodiversity helps reefs survive. We want to know more.”

The study’s insights could aid ecologists restocking crumbling reefs with corals—which are animals. Past replenishing efforts have often deployed patches of single species that have had trouble taking hold, and the researchers believe the study should encourage replanting using biodiverse patches.

40 years of death

The decimation of corals Hay has witnessed in over four decades of undersea research underscores this study’s importance.

“It’s shocking how quickly the Caribbean reefs crashed. In the 1970s and early 1980s, reefs consisted of about 60 percent live coral cover,” Hay says. “Coral cover declined dramatically through the 1990s and has remained low. It’s now at about 10 percent throughout the Caribbean.

“You used to find living diverse reefs with structurally complex coral stands the size of city blocks. Now, most Caribbean reefs look more like parking lots with a few sparse corals scattered around.”

The fact that the decimation in the Pacific is less grim is bitter irony. About half of living coral cover disappeared there between the early 1980s and early 2000s with declines accelerating since.

“From 1992 to 2010, the Great Barrier Reef, which is arguably the best-managed reef system on Earth, lost 84 percent,” Clements says. “All of this doesn’t include the latest bleaching events reported so widely in the media, and they killed huge swaths of reef in the Pacific.”

The 2016 bleaching event also sacked reefs off of Fiji where the researchers ran their experiment. The coral deaths have been associated with extended periods of ocean heating, which have become much more common in recent decades.

Reasons for optimism

Still, there’s hope. Pacific reefs support 10 times as many coral species as Caribbean reefs, and Clements’ and Hay’s new study suggests that this higher biodiversity may help make these reefs more robust than the Caribbean reefs. There, many species have joined the endangered list, or are “functionally extinct,” still present but in traces too small to have an ecological impact.

The Caribbean’s coral collapse may have been a warning shot on the dangers of species loss. Some coral species protect others from getting eaten or infected, for example.

“A handful of species may be critical for the survival of many others, and we don’t yet know well enough which are most critical. If key species disappear, the consequences could be enormous,” says Hay, who believes he may have already witnessed this in the Caribbean. “The decline of key species may drive the decline of others and potentially create a death spiral.”

Setting coral tables

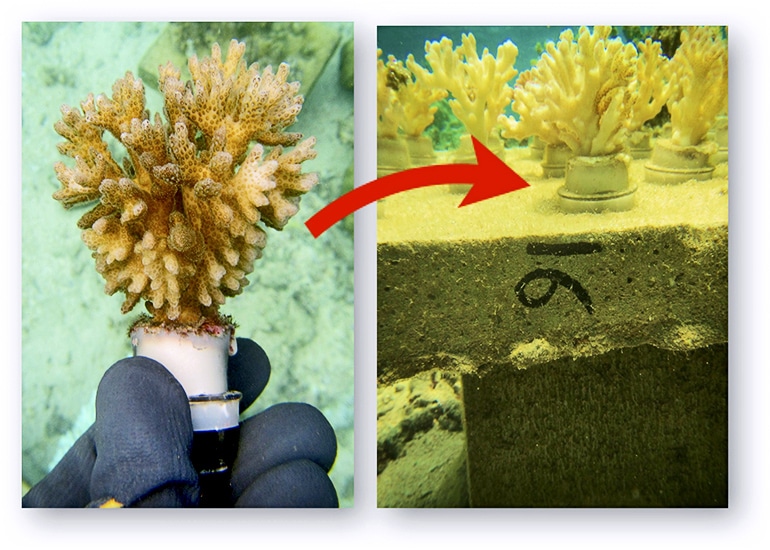

Off Fiji’s shores, Clements transported by kayak, one by one, 48 concrete tables he had built on land. He put them into place and mounted on top of them 864 jaggy corals in planters he had fashioned from the tops of plastic soda bottles.

“I scratched a lot of skin off of my fingers screwing those corals onto the tables,” he says, laughing at the memory. “I drank enough saltwater through my snorkel doing it, too.”

Clements laid out 18 corals on each tabletop: Three groups of monocultures filled 36 tables (12 with species A, 12 with species B, 12 with species C). The remaining 12 tabletops held polycultures with balanced A-B-C mixtures. He collected data four months into the experiment and at 16 months.

The polycultures all looked great. Only one monoculture species, Acropora millepora, had nice growth at the 16-month mark, but that species is more susceptible to disease, bleaching, predators, and storms. It may have sprinted ahead in growth in the experiment, but long-term it would probably need the help of other species to cope with its own fragility.

“Corals and humans both may do well on their own in good times,” Hay says. “But when disaster strikes, friends may become essential.”

The results of the study appear in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

The National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health’s Fogarty International Center, and the Teasley Endowment funded the research. Any findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and not necessarily of the funding entities.

Source: Georgia Tech