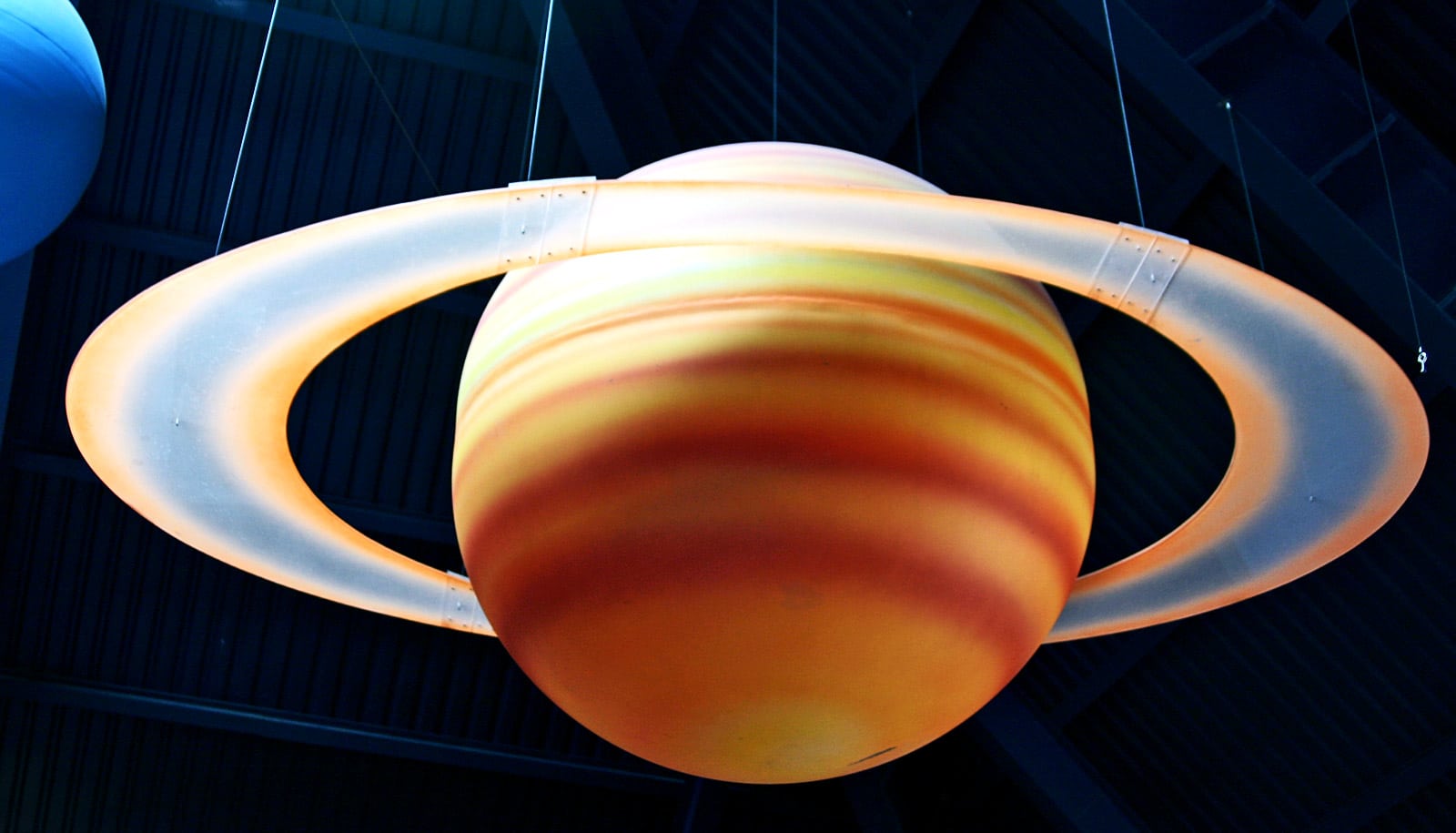

Saturn’s beautiful, extensive rings are relatively young, perhaps created when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, according to new study.

Scientists drew the conclusion after finding that the ring’s mass is less than previously thought and its frozen components are surprisingly bright and free from dusty cosmic impurities.

“Based on previous research, we suspected the rings were young, but not everyone was convinced,” says study coauthor Phil Nicholson, professor of astronomy at Cornell University.

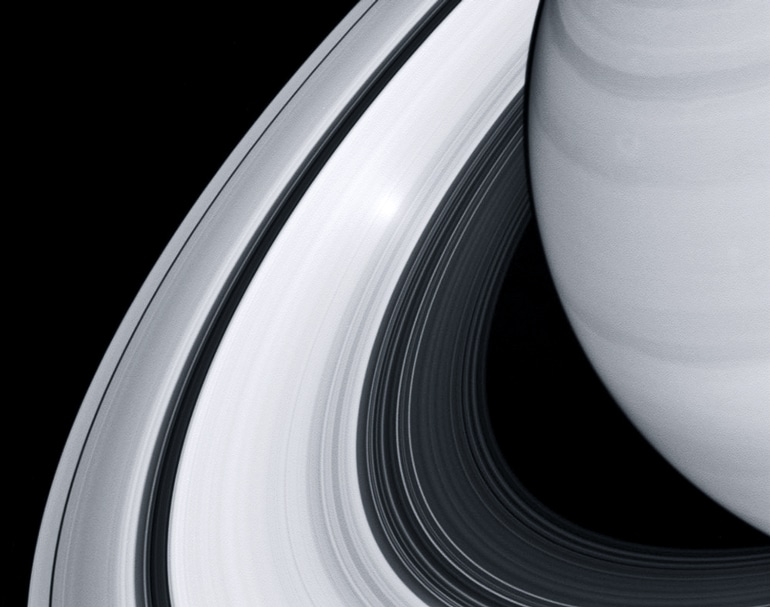

Before Cassini’s demise when it crashed into Saturn in September 2017, the spacecraft passed repeatedly between the rings and the planet’s cloud tops to study Saturn’s gravity field and the rings’ mass.

Cassini (and two Voyager spacecraft) had studied Saturn’s rings from afar, but no craft had yet ventured into the rings to obtain up-close data. Before its final planetary plunge, Cassini dove through the rings 22 times, using six passes to measure the gravity field by tracking the radio signal from the spacecraft. (The technique is similar to a police radar, but more precise; researchers measured Cassini with an accuracy of better than 0.1 millimeter per second.)

The scientists found that the rings—particularly the dense B-ring, one of the three main rings and the brightest visible in a telescope—had lower masses than many expected, indicating a relatively young age. While Saturn is about 4.5 billion years old, the new Cassini data indicate that the rings probably formed between 10 million and 100 million years ago, according to the researchers.

If interplanetary debris contaminated and darkened the rings over a longer period, they would appear much darker, according to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“The new mass measurement is firm, because Cassini was able to pass inside the rings. In our prior research, we used waves driven in the rings by Saturn’s moons to indirectly estimate their mass density at several locations, which we then extrapolated to estimate the total mass of the rings,” says Nicholson, who conducted the earlier research with Matt Hedman, now an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Idaho. “Our final result was very close to the new measurement, but lower than most earlier estimates.”

“From what we know based on Cassini’s spectral and radar measurements, the rings are also less contaminated than previously thought—probably less than 1 percent,” says Nicholson. “They are close to pure water ice.”

In 2016, Zhimeng Zhang conducted work examining the dust content of Saturn’s C ring. This research determined that the C ring, once thought to have formed in the primordial era, was less than 100 million years old. In 2017, she and her colleagues reported on similar measurements of the A and B rings, obtaining similarly young ages.

“Think of an unused desk in an unused room. The more it sits there, the more it collects dust,” Zhang said when she published her work. “The C ring is the same way. While it is composed mostly of water ice, it collects silicate-containing dust from the far-off Kuiper Belt.… [I]n this case, the dust—in terms of the age of the solar system—has not been here a long time.”

Among ring scientists, Nicholson and others wagered what Cassini might find in terms of ring mass. The result was close to Nicholson’s prediction.

“This is quite gratifying from a scientific and personal point-of-view that we got close to the real number when Cassini finally measured it,” he says.

The study appears in Science. Additional researchers are from Sapienza University in Rome.

Source: Cornell University