Most people can’t tell native advertising apart from actual news articles, according to new research.

There are all kinds of ways to avoid advertising, such as using ad-blocker software, fast-forwarding through commercials, or choosing ad-free media streaming services like Netflix. This has forced advertisers to get creative to put their messages in front of digital consumers. Also known as sponsored content, native advertising inserts paid messaging right into the mix alongside news articles.

Buzzfeed was an early adopter of native advertising as a profit-making model, but these days the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Boston Globe, and nearly all major news sites are profiting from content for which advertisers pay. One estimate from Forbes says that native ads will be a $21 billion industry by 2021 and account for nearly 75 percent of all ad revenue by then.

Not only is there more content like this, it’s better, too. So much better that it’s beginning to fake out readers. And that’s troubling, says Michelle Amazeen, an assistant professor of advertising at the Boston University School of Communication.

In her new research, even though her online survey told participants that they were viewing advertisements, many people—more than 9 out of 10—thought they were looking at an article.

“I think it’s contributing to people thinking that news media are sharing fake news,” says Amazeen, corresponding author of the study, which appears in Mass Communication and Society.

Ad or article?

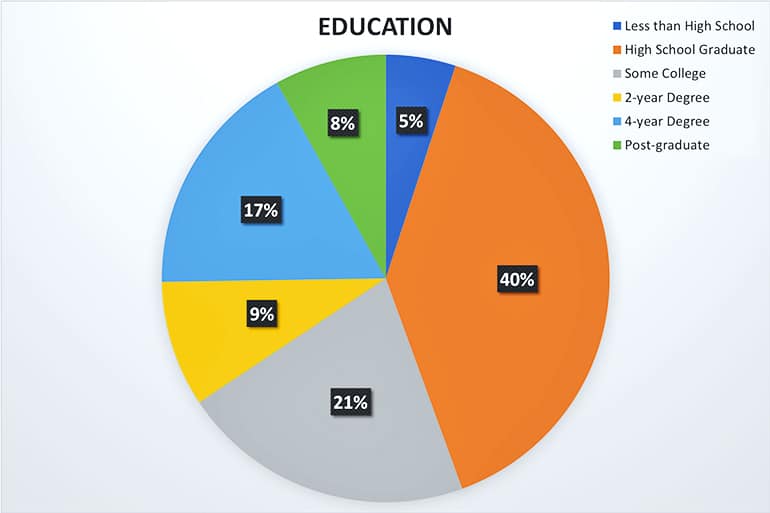

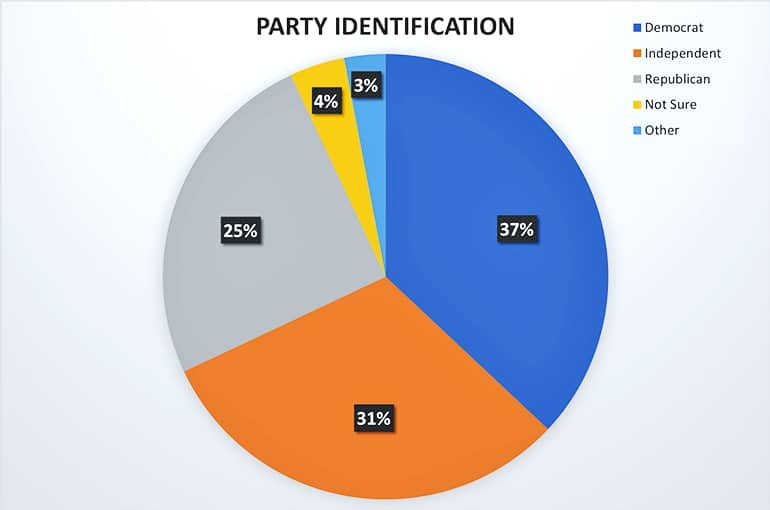

During the online experiment, Amazeen and her collaborator, Bartosz Wojdynski of the University of Georgia, surveyed 738 adults—a cross section of people of all ages, with varying degrees of education, both married and single, and from across the political spectrum.

During the survey, the participants viewed content from an actual Bank of America advertisement, a 515-word piece titled “America’s Smartphone Obsession Extends to Online Banking,” which Brandpoint, a content marketing agency, created for the bank.

Participants viewed the advertisement, which included a disclosure identifying it as an ad—the Federal Trade Commission requires that advertisers include such a disclosure—and then answered a series of questions.

Amazeen found that among the fewer than 1 in 10 individuals who were able to identify the Bank of America piece as advertising, people tended to be younger, more educated, and more likely to describe their engagement with news media as for informational purposes. In contrast, people who mistook the advertisement for a legitimate news article were generally older, less educated, and more likely to consume news media for entertainment purposes.

“We found that people are more receptive to what they’re looking at if they know what they’re reading,” Amazeen says, even if they know they’re reading an ad.

If, on the other hand, an advertiser makes it difficult to detect content as an ad, a substantial amount of people have negative reactions when they realize the truth.

“A lot of people equate this to fake news,” Amazeen says. “Trust in media is at an all-time low…. I’m not suggesting it’s only from native advertising, but I think it’s a contributing factor.”

Is a ‘sponsored content’ label enough?

Although advertisers are required to disclose their ads as such, typically with a label like “sponsored” or “paid promotion,” not all disclosures are the same. Depending on size, placement, and other factors, some advertisers and publishers are more upfront than others about the nature of their content. Amazeen says the lack of standardized requirements for native ad disclosures is fueling the problem of people not recognizing what’s a sponsored story and what’s a news story.

One big risk, Amazeen says, is that if someone doesn’t realize they’re looking at promoted content, they may think they’re getting the whole story on a given topic.

“Advertising is supposed to be true and accurate, according to the Federal Trade Commission,” Amazeen says. But, ads often “leave out certain information that isn’t favorable for whatever perspective they are trying to convey.”

In an effort to combat public distrust, some news organizations are taking more aggressive initiatives to help readers identify real content versus sponsored content. But, with native advertisements peppering most newsfeeds, a state of constant confusion over content—what is editorial, what is sponsored, and what is just outright fake—is muddying the waters.

‘Shooting themselves in the foot’

“A lot of legacy and digital-only news organizations do fantastic investigative reporting and break important stories, but at the same time, they’re shooting themselves in the foot,” Amazeen says.

Politico, for example, runs a fake news database, filled with news stories that its reporters or readers have found to contain doctored videos, images, or hoax-like disinformation. However, Politico’s own news feed is sporadically interspersed with advertisers’ articles labeled as sponsored.

“Politico’s concern with the origins of political disinformation seems pretty rich given its work with Cambridge Analytica,” Amazeen wrote in an October 2018 tweet.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, political consulting firm Cambridge Analytica helped target 10,000 ads to different audiences. Brittany Kaiser, who was Cambridge Analytica’s business development director at the time, called one native advertisement on Politico, “the most successful thing we pushed out.”

In March 2018, an article in the Guardian reported, “One of the most effective ads, according to Kaiser, was a piece of native advertising on the political news website Politico, which was also profiled in the presentation. The interactive graphic, which looked like a piece of journalism and purported to list ’10 inconvenient truths about the Clinton Foundation,’ appeared for several weeks to people from a list of key swing states when they visited the site. It was produced by the in-house Politico team that creates sponsored content.”

The advertisement on Politico, which was labeled at the top as “sponsor-created content” and “paid advertisement for and created by Donald J. Trump,” garnered an average of four minutes of engagement from its readers in key swing states.

“The line of caution is when you start mixing news with advertisements and blurring those lines—that’s where you have to take a step back and really think about what you’re doing,” Amazeen says.

The American Press Institute funded the research.

Source: Boston University