Artifacts from a South China archaeological site show that sophisticated tool technology emerged in East Asia earlier than previously thought, say researchers.

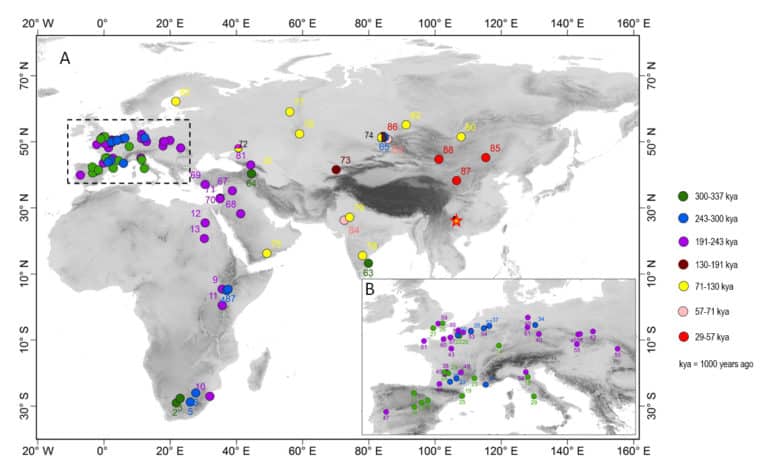

The new analysis determines that people used carved stone tools, also known as Levallois cores, in Asia 80,000 to 170,000 years ago. Developed in Africa and Western Europe as far back as 300,000 years ago, the cores are a sign of more-advanced toolmaking—the “multi-tool” of the prehistoric world—but, until now, were not believed to have emerged in East Asia until 30,000 to 40,000 years ago.

The work “shows the diversity of the human experience.”

With the find—and absent human fossils linking the tools to migrating populations—researchers believe people in Asia developed the technology independently, evidence of similar sets of skills evolving throughout different parts of the ancient world.

“It used to be thought that Levallois cores came to China relatively recently with modern humans,” says Ben Marwick, associate professor of anthropology at the University of Washington and a corresponding author of the paper in Nature. “Our work reveals the complexity and adaptability of people there that is equivalent to elsewhere in the world. It shows the diversity of the human experience.”

Levallois-shaped cores—the “Swiss Army knife of prehistoric tools,” Marwick says—were efficient and durable, indispensable to a hunter-gatherer society in which a broken spear point could mean certain death at the claws or jaws of a predator. The cores get their name from the Levallois-Perret suburb of Paris, where stone flakes were found in the 1800s.

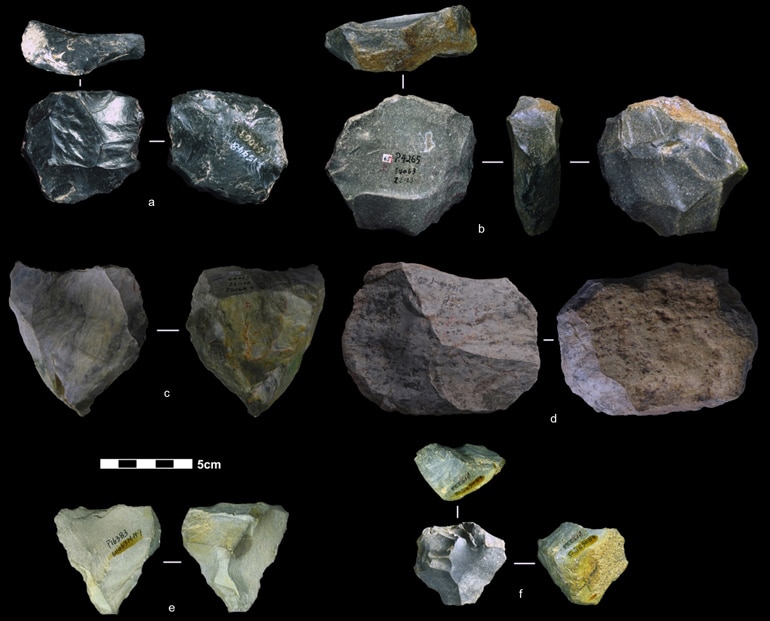

Featuring a distinctive faceted surface, created through a sequence of steps, Levallois flakes were versatile “blanks,” used to spear, slice, scrape, or dig. The knapping process represents a more sophisticated approach to tool manufacturing than the simpler, oval-shaped stones of earlier periods.

When did the artifacts last see the sun?

The Levallois artifacts in this study were excavated from Guanyindong Cave in Guizhou Province in the 1960s and 1970s. Previous research using uranium-series dating estimated a wide age range of the archaeological site—between 50,000 and 240,000 years old—but that earlier technique focused on fossils found away from the stone artifacts, Marwick says. Analyzing the sediments surrounding the artifacts provides more specific clues as to when the artifacts would have been in use.

“Technological innovations in East Asia can be homegrown, and don’t always walk in from the West.”

Marwick and other members of the team, from universities in China and Australia, used optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to date the artifacts. OSL can establish age by determining when a sediment sample, down to a grain of sand, was last exposed to sunlight—and thus, how long an artifact may have been buried in layers of sediment.

“Dating for this site was challenging because it had been excavated 40 years ago, and the sediment profile was exposed to air and without protection. So trees, plants, animals, insects could disturb the stratigraphy, which may affect the dating results if conventional methods were used for dating,” says Bo Li, an associate professor of archaeology at the University of Wollongong in Australia and one of the paper’s corresponding authors.

“To solve this problem we used a new single-grain dating technique…to date individual mineral grains in the sediment. Luckily we found residual sediment left over by the previous excavations, so that allowed us to take samples for dating.”

The researchers analyzed more than 2,200 artifacts from Guanyindong Cave, narrowing down the number of Levallois-style stone cores and flakes to 45. Among those believed to be in the older age range, about 130,000 to 180,000 years old, the team also was able to identify the environment in which people used the tools: an open woodland on a rocky landscape, in “a reduced rainforest area compared to today,” the authors note.

Stereotypes about innovation

In Africa and Europe these kinds of stone tools often turn up at archaeological sites starting from 300,000 and 200,000 years ago. They are known as Mode III technology, part of a broad evolutionary sequence that was preceded by hand-axe technology (Mode II) and followed by blade tool technology (Mode IV).

Archaeologists thought that Mode IV technologies arrived in China by migration from the West, but these new finds suggest they could have been locally invented. At the time people were making tools in Guanyindong Cave, the Denisovans—ancestors to Homo sapiens and relative contemporaries to Neandertals elsewhere in the world—roamed East Asia. But while hundreds of fossils of archaic humans and related artifacts, dating as far back as more than 3 million years ago, have been found in Africa and Europe, the archaeological record in East Asia is sparser.

That’s partly why a stereotype exists, that ancient peoples in the region were behind in terms of technological development, Marwick says.

“Our work shows that ancient people there were just as capable of innovation as anywhere else. Technological innovations in East Asia can be homegrown, and don’t always walk in from the West,” he says.

Same innovations, different locations

The independent emergence of the Levallois technique at different times and places in the world is not unique in terms of prehistoric innovations. Pyramid construction, for one, appeared in at least three separate societies: the Egyptians, the Aztecs, and the Mayans. Boatbuilding began specific to geography and reliant on a community’s available materials. And writing, of course, developed in various forms with distinct alphabets and characters.

In the evolution of tools, Levallois cores represent something of a middle stage. Subsequent manufacturing processes yielded more-refined blades made of rocks and minerals that were more resistant to flaking, and composites that, for example, combined a spear point with blades along the edge. The appearance of blades later in time indicates a further increase in the complexity and the number of steps required to make the tools.

“The appearance of the Levallois strategy represents a big increase in the complexity of technology because there are so many steps that have to work in order to get the final product, compared to previous technologies,” Marwick says.

Funding for the study came from the Australian Research Council, the National Science Foundation of China, the University of Wollongong, the China Scholarship Council, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the State Key Laboratory of Loess and Quaternary Geology.

Additional coauthors of the paper are from the University of Wollongong; Peking University in China; the Chinese Academy of Sciences; and the Bureau of Cultural Relics Protection in Guizhou Province, China.

Source: University of Washington