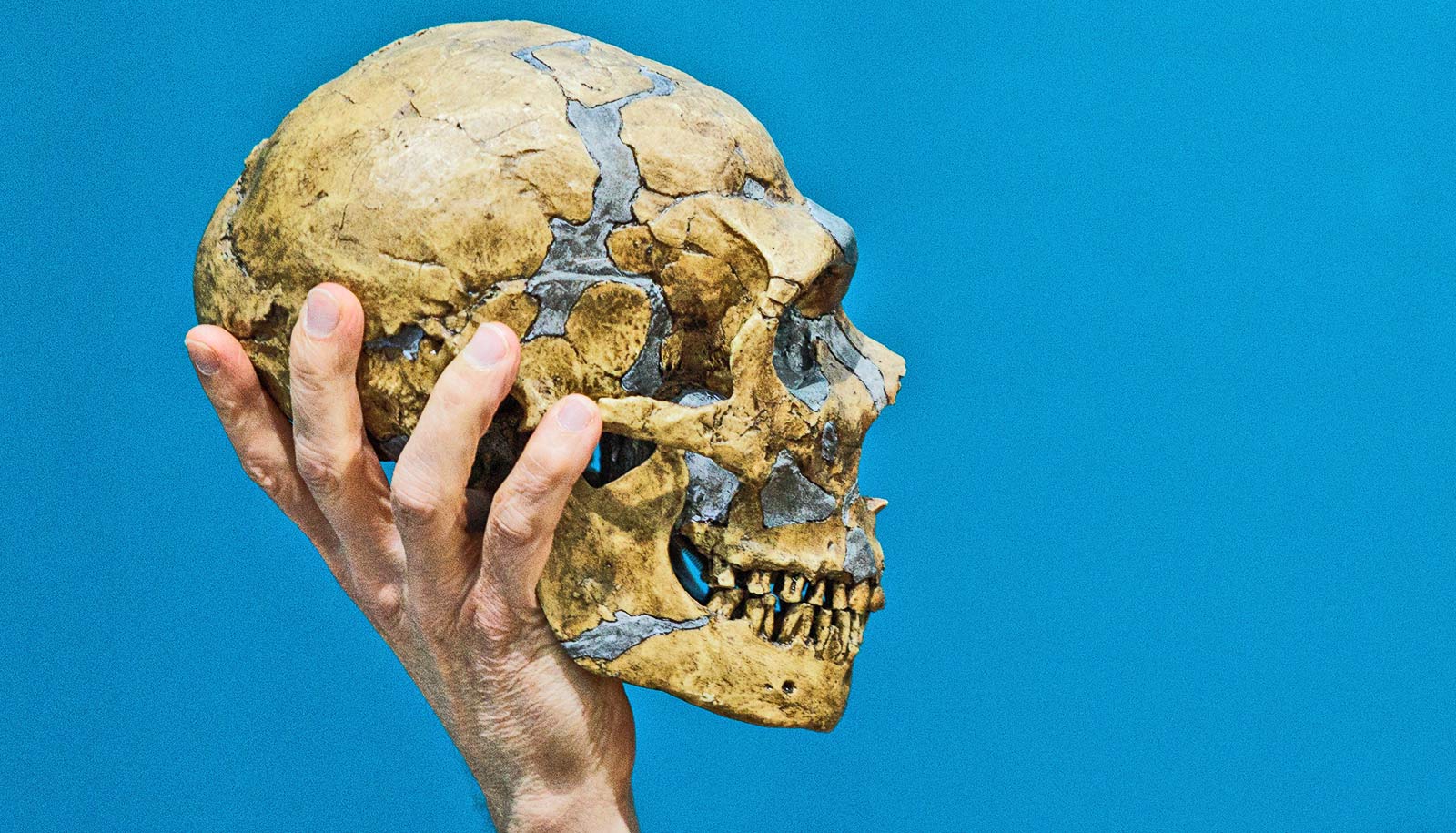

DNA samples are giving scientists a clearer picture of 6th-century barbarian migrations, according to new research.

By taking extensive DNA samples from the skulls of individuals buried in two European cemeteries—one in Italy and one in Hungary—and combining that data with artifacts from the ancient civilization, scientists are now better able to piece together how barbarians invading from north of the declining Roman Empire interacted with local populations during the European Migration Period (4th to 8th centuries), laying the foundation for modern European society.

The study, which appears in Nature Communications, is the first cross-discipline analysis of 6th-century barbarian cemeteries and contains the largest number of genomes generated from a single ancient site to date.

“Our study provided clear evidence of migrations from Pannonia to Italy described in historic texts and by the Romans,” says study leader Krishna Veeramah, assistant professor in the ecology and evolution department at Stony Brook University.

“Interestingly, DNA reveals that biological kinship was a key part of these societies, mainly among males, and women were probably acquired at different points during migrations,” he says.

Additionally, in both cemeteries individuals buried with elaborate grave goods, like swords and shields for men and necklaces on women, had genomic ancestry associated with northern and central Europeans, while those buried without these kinds of goods had southern European genomes.

The research team points out that the study sheds light on new ways to help historians understand the complexity and heterogeneity of Europe’s past and present populations.

The team is looking to complete similar studies at sites in other areas of Europe to help solve the puzzle of the Migration Period and better understand the various demographic processes that led to modern Europe.

The National Science Foundation funded the research in part.

Source: Stony Brook University