The ocean is no longer the wild frontier it once was. In fact, a new study finds that only 13 percent of the ocean still counts as wilderness.

“The idea of wilderness is powerful for people, as well as for nature,” says Ben Halpern, director of the University of California, Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis and a contributing author of the study.

“Just knowing wilderness exists provides a sense of existential value to many people, that nature still exists somewhere in a relatively untouched form, even if they never actually visit the wilderness.” However, thanks to human activity, the vast majority of the world’s oceans have lost that “untouched” status.

“Those marine areas that can be considered ‘pristine’ are becoming increasingly rare, as fishing and shipping fleets expand their reach across almost all of the world’s oceans, and sediment runoff smothers many coastal areas,” says Kendall Jones, a researcher at the University of Queensland, and lead author of the paper.

According to the study, which appears in Current Biology, most remaining marine wilderness is unprotected, leaving it vulnerable to being lost.

“Improvements in shipping technology mean that even the most remote wilderness areas may come under threat in the future, including once ice-covered places that are now accessible because of climate change,” Jones says.

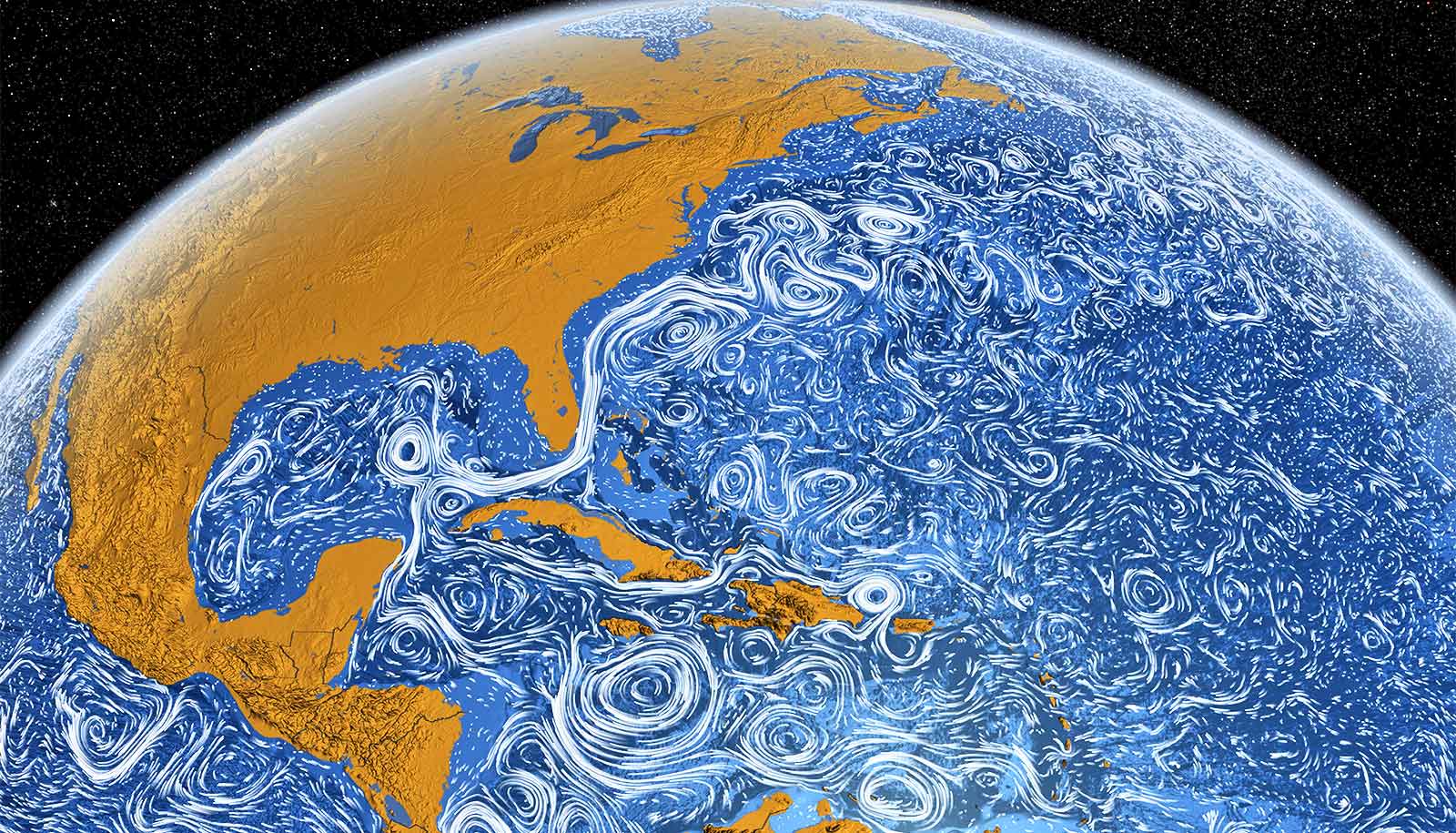

The authors used fine-scale global data on 19 human stressors to the ocean, including commercial shipping, sediment runoff, and several types of fishing, to identify Earth’s remaining marine wilderness—areas devoid of intense human impacts.

They found that most wilderness is located in the Arctic and Antarctic or around remote Pacific island nations such as French Polynesia. Because human activities are concentrated near land, very little wilderness remains in coastal habitats such as coral reefs, salt marshes, and kelp forests.

The findings highlight an immediate need for conservation policies to recognize and protect the unique values of marine wilderness, says James Watson, a professor at the University of Queensland, director of science at the Wildlife Conservation Society, and senior author of the research paper.

“Marine wilderness areas are home to unparalleled levels of life—holding massive abundances of species and high genetic diversity, giving them resilience to threats like climate change,” he says.

Air pollution in national parks may keep visitors away

Watson argues that the need to focus attention and resources on preserving the ocean’s remaining wilderness is more urgent than ever.

“We know these marine wilderness areas are declining catastrophically, and protecting them must become a focus of multilateral environmental agreements,” he says. “If not, they will likely disappear within 50 years.”

The authors say that preserving marine wilderness also requires regulating the high seas, which has historically proven difficult since no country has jurisdiction of these areas. However, Jones notes that a recent United Nations resolution could change this.

Rivers cover a lot more of Earth than we thought

“Late last year the United Nations began developing a legally binding high seas conservation treaty—essentially a Paris Agreement for the ocean,” Jones says. “This agreement would have the power to protect large areas of the high seas and might be our best shot at saving some of Earth’s last remaining marine wilderness.”

Source: UC Santa Barbara