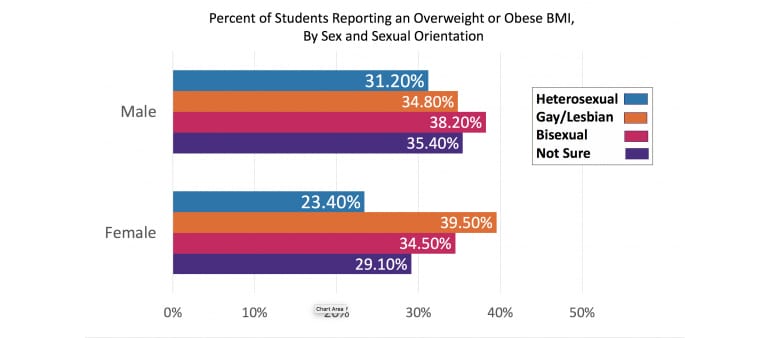

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes and to be obese, research shows. The findings also suggest they engage in less physical activity, and opt for more sedentary activities than their heterosexual peers do.

The study examines how health behaviors linked to minority stress—the day-to-day stress that stigmatized and marginalized populations face—may contribute to the risk of poor physical health among LGBQ youth.

“Many of these youth might be taking part in sedentary activities—like playing video games—to escape the daily stress tied to being lesbian, gay, bisexual, or questioning.”

“Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth may not only be at risk for worse mental health but also worse physical health outcomes compared to heterosexual youth,” says lead author Lauren Beach, a postdoctoral research fellow at Northwestern University’s Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing.

This is the largest study to date to report differences in levels of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and obesity by sex and sexual orientation among high-school-aged students.

The authors used national data from 350,673 United States high-school students, predominantly ranging between 14 and 18 years old, collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as part of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) to detect disparities in diabetes risk factors by sexual orientation.

The study appears in Pediatric Diabetes. Here are some key findings:

- On average, sexual minority and questioning students were less likely to engage in physical activity than heterosexual students. They reported approximately one less day per week of physical activity and were 38 to 53 percent less likely to meet physical activity guidelines than heterosexual students.

- The number of hours of sedentary activity among bisexual and questioning students was higher than heterosexual students (an average of 30 minutes more per school day than heterosexual counterparts).

- Lesbian, bisexual, and questioning female students were 1.55 to 2.07 times more likely to be obese than heterosexual female students.

Obesity and sedentary activity may be higher in this population because lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youth are subjected to minority stress, Beach says.

“Many of these youth might be taking part in sedentary activities—like playing video games—to escape the daily stress tied to being lesbian, gay, bisexual or questioning,” Beach says. “Our findings show that minority stress actually has a very broad-ranging and physical impact.

“Previous research has shown that body image and standards of beauty might be different among LGBQ compared to heterosexual populations. We know very little about the physical environments of LGBQ youth. Are these youth less likely to live in areas that are safe for them to be active? We just don’t know.”

The findings shouldn’t be viewed as a “doomsday” for this population, Beach says. Instead, she believes it’s an opportunity to improve the health of sexual minority and questioning youth.

Parents feel weird about sex ed for LGBTQ teens

Teachers, parents and physicians should work together to make sure these teens have the tools they need to stay healthy, Beach says. Family support and identity affirmation—developing positive feelings and a strong attachment to a group—have been consistently linked to better health among LGBQ youth.

In addition to providing an overall supportive environment, parents should consider asking their children, “Have you been physically active today? Are you active in gym class? Can we do something today to be active together?”

Trans and gender-fluid teens face 3X more abuse

Further, parents should be proactive at doctor appointments and ask the doctor to screen for physical activity, screen time, diet, and their child’s weight, Beach adds.

Previous studies have examined diabetes and cardiovascular health among LGBTQ people, but that research has largely focused only on adults.

“This is the biggest study of its kind but it’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Beach says. “There’s still so much we don’t know, such as what is causing these disparities and what can be done about it. It’s a completely untapped field of research.”

A National Institutes of Health grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism funded the work.

Source: Northwestern University