Researchers have developed a high-tech fix that uses metal nanostructures to increase the fluorescence intensity by 100 times in diagnostic tests. It’s a cheap and easy solution to a vexing diagnostic problem.

Fluorescence-based biosensing and bioimaging technologies are common in research and clinical settings to detect and image various biological species of interest. While fluorescence-based detection and imaging techniques are convenient to use, they suffer from poor sensitivity.

For example, when a patient carries low levels of antigens in the blood or urine, the fluorescent signal can be feeble, making visualization and diagnosis difficult. For this reason, fluorescence-based detection is not always ideal when sensitivity is a key requirement.

“Using fluorescence for biodetection is very convenient and easy, but the problem is it’s not that sensitive, and that’s why researchers don’t want to rely on it,” says Srikanth Singamaneni, professor of mechanical engineering & material science at the Washington University in St. Louis School of Engineering & Applied Science.

As the team explains in the journal Light: Science and Applications, techniques to boost the signal—such as relying on enzyme-based amplification—require extra steps that prolong the overall operation time, as well as specialized and expensive read-out systems in some cases.

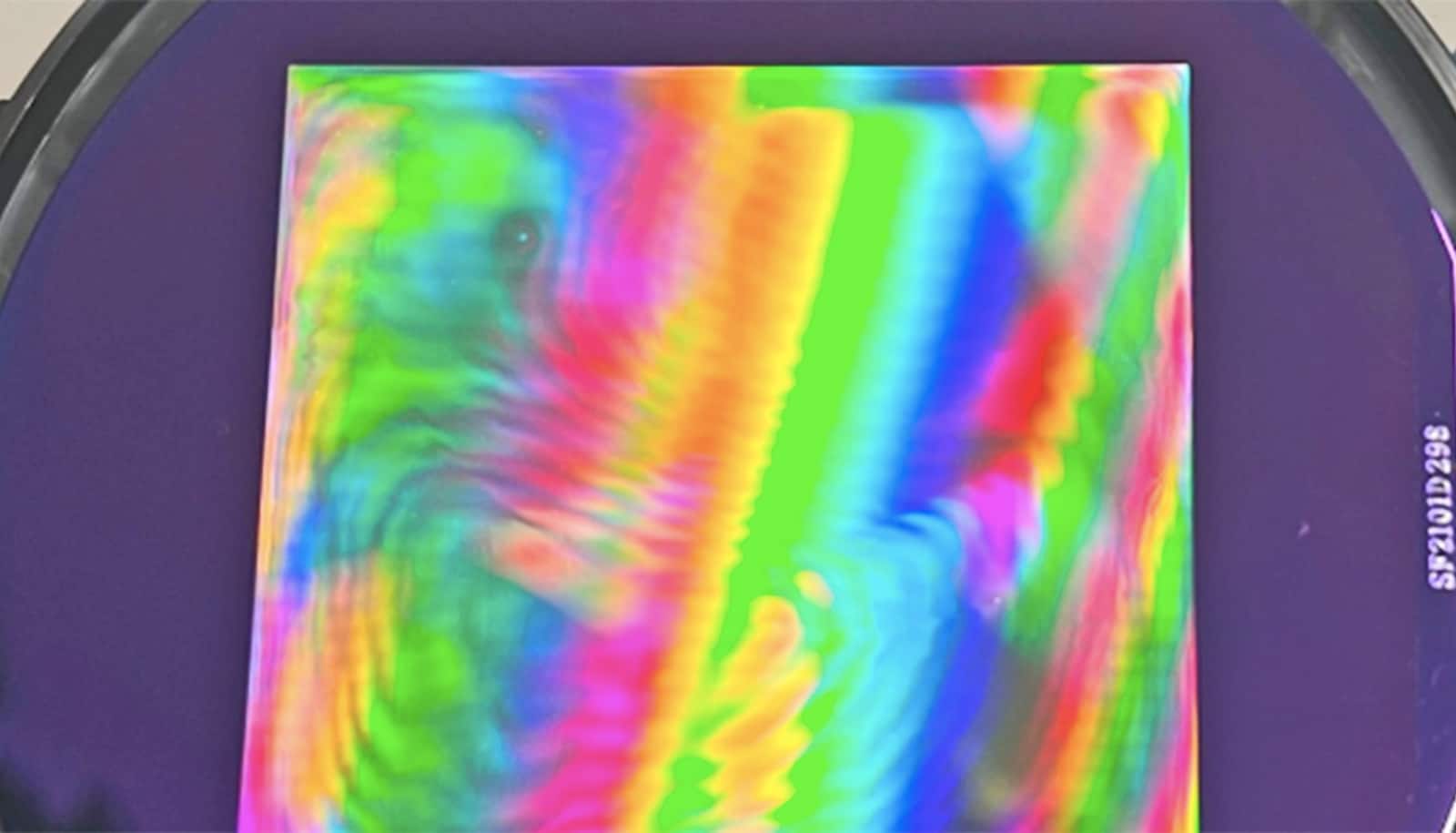

However, the “plasmonic patch” developed by Singamaneni and coworkers doesn’t require any change in testing protocol. The patch is a flexible piece of film about a centimeter square, embedded with nanomaterials. All a researcher or lab tech needs to do is prepare the sample in the usual method, apply the patch over the top, and then scan the sample as usual.

“It’s a thin layer of elastic, transparent material with gold nanorods or other plasmonic nanostructures absorbed on the top,” says Jingyi Luan, a graduate student in the Singamaneni Lab and primary author of the manuscript.

“These nanostructures act as antennae: they concentrate light into a tiny volume around the molecules emitting fluorescence. The fluorescence is dramatic, making it easier to visualize. The patch can be imagined to be a magnifying glass for the light.”

Singamaneni says the newly developed patch is a cheap fix—costing only about a nickel per application—and one that contains not only research applications but also diagnostics. It could be particularly useful in a microarray, which enables simultaneous detection of tens to hundreds of analytes in a single experiment.

Light-up specks find and track tiny tumors

“The plasmonic patch will enable the detection of low abundance analytes in combination with conventional detection methodologies, which is the beauty of our approach,” says Rajesh Naik, chief scientist of the 711th Human Performance Wing of the Air Force Research Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

“It’s a last step, just like a Band-Aid,” Singamaneni says. “You apply it, and the dimness problem in these fluorescence-based detection methods is solved.”

The National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Research Foundation funded the research. Washington University’s Office of Technology Management also provided funding.