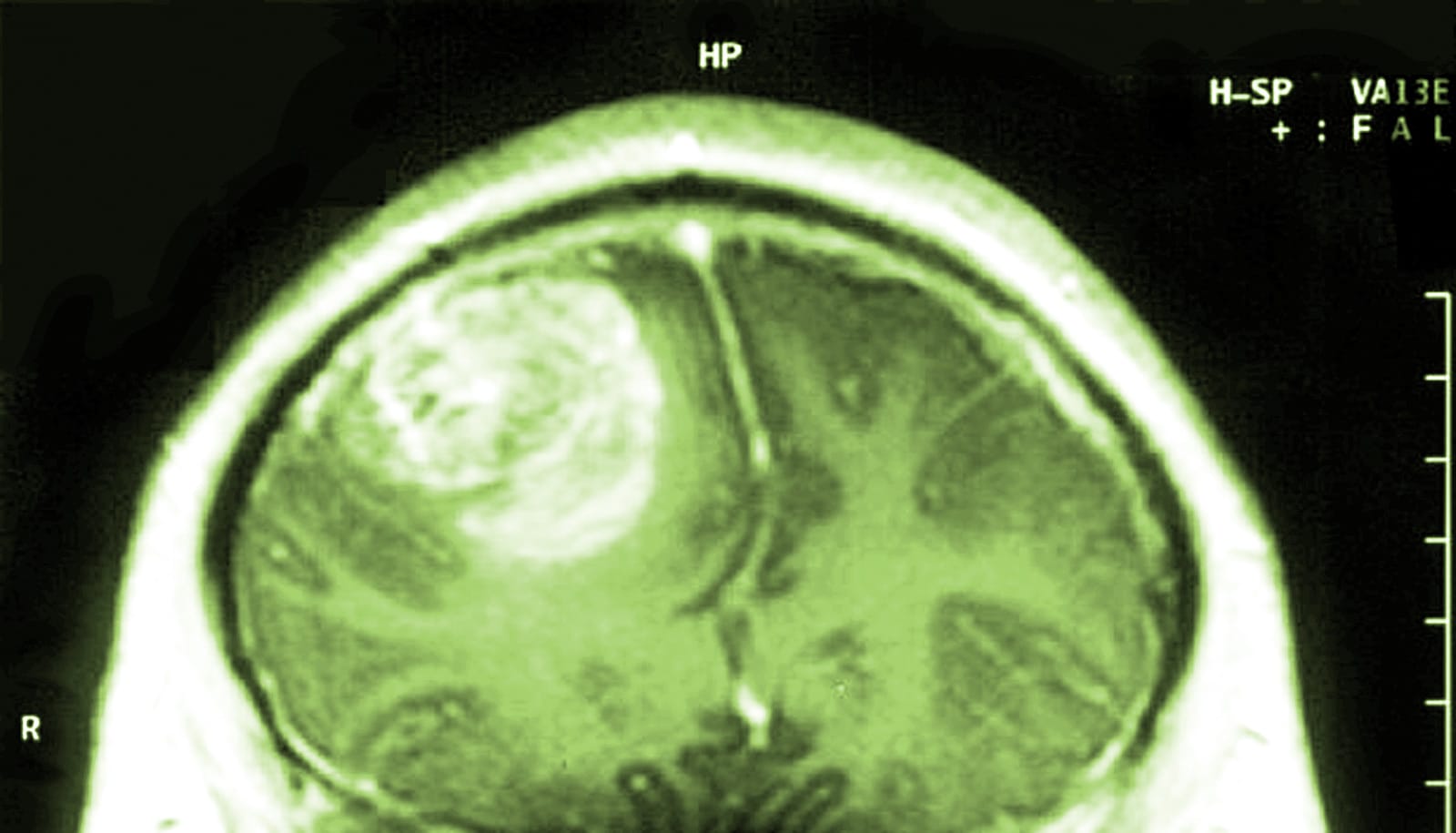

A genetically modified poliovirus therapy significantly improved long-term survival for patients with recurrent glioblastoma, with a three-year survival rate of 21 percent, a new study shows.

Comparatively, just 4 percent of patients with the same type of recurring brain tumors were alive at three years when undergoing the previously available standard treatment.

“Glioblastoma remains a lethal and devastating disease, despite advances in surgical and radiation therapies, as well as new chemotherapy and targeted agents,” says Darell D. Bigner, emeritus director of the Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center at Duke University and senior author of the study in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“There is a tremendous need for fundamentally different approaches,” Bigner says “With the survival rates of this early phase of the poliovirus therapy, we are encouraged and eager to continue with the additional studies that are already underway or planned.”

Researchers reported median follow-up of 27.6 months in the phase 1 trial, which launched in 2012 with a young patient who was just entering nursing school. She has since married and works as a registered nurse.

The therapy includes a genetically modified form of the poliovirus vaccine, which is infused directly into the brain tumor via a surgically implanted catheter. Developed by Matthias Gromeier in his lab at Duke, the modified virus preferentially zeroes in on tumor cells, igniting a targeted immune response. Gromeier and coauthors recently published a study in Science Translational Medicine describing the mechanism of action for the poliovirus therapy.

“…some patients don’t respond for one reason or another, but if they respond, they often become long-term survivors. The big question is, how can we make sure that everybody responds?”

An 18-year collaboration with the National Cancer Institute’s Experimental Therapeutics (NExT) Program, NCI, part of the National Institutes of Health, and the US Food and Drug Administration enabled the pre-clinical and translational phases of development of the new therapy for glioblastoma.

“The Duke and NCI teams collaborated extensively on the preclinical work, which has culminated in these clinical trial results,” says Jim Doroshow, deputy director for Clinical and Translational Research at NCI.

Initially in the phase 1 clinical trial, researchers planned to increase the dosage of the therapy infusion; a safe dose amount is a primary goal of first-phase studies. But at higher dosages, some patients experienced too much inflammation, resulting in seizures, cognitive disturbances, and other adverse events, so the amount infused was reduced. All but 15 of the 61 patients enrolled in the study had one of the lower dosages.

Study participants were selected according to strict guidelines based on the size of their recurring tumor, its location in the brain, and other factors designed for patient protection. A comparison group of patients was drawn from historical cases at Duke involving patients who would have matched the poliovirus enrollment criteria.

For all 61 poliovirus patients, the median overall survival was 12.5 months, compared to 11.3 months for the historical control group. Starting at two years after treatment, the survival curves in the two groups diverged.

The rate of overall survival of poliovirus patients at 24 months was 21 percent, compared to 14 percent for the historical controls. At three years, the gap widened further, with a survival rate of 21 percent for poliovirus patients, compared to 4 percent in the control group.

“Similar to many immunotherapies, it appears that some patients don’t respond for one reason or another, but if they respond, they often become long-term survivors,” Desjardins says. “The big question is, how can we make sure that everybody responds?”

Combining the poliovirus with other approved therapies is one approach already in testing at Duke to improve survival. A phase 2 study now underway combines the poliovirus therapy with the chemotherapy drug lomustine for patients with recurrent glioblastomas.

The authors report that 69 percent of study patients had a mild or moderate adverse event attributed to poliovirus as their most severe side effect. Low dose bevacizumab was used to help control the localized inflammation of the tumor and its side effects.

Could time of day boost chemo for glioblastoma?

The poliovirus therapy obtained “breakthrough therapy designation” in 2016 from the US Food and Drug Administration.

New trials have already resulted. In addition to the phase 2 trial for glioblastoma, enrollment began this year to test the therapy in pediatric brain tumors. Some breast cancer and melanoma patients will soon be eligible to join clinical trials that expand the therapy beyond brain tumors.

This protein flags the worst glioblastomas

The work received grant support from the Brain Tumor Research Charity, the Tisch family through the Jewish Communal Fund, Circle of Service Foundation, Uncle Kory Foundation, Department of Defense, and National Institutes of Health. An Angels Among Us fundraising event and a gift from the Asness family also provided funding. The NIH provided the foundational poliovirus to produce the therapy.

Study authors received no commercial support for the design or implementation of the clinical trial. Authors Desjardins, Gromeier, Bolognesi, Allan Friedman, Henry Friedman, Sampson and Bigner are named on patents licensed from Duke University to a start-up company, Istari Oncology.

Source: Duke University