2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is arguably the world’s most influential science fiction film. Stanley Kubrick’s space epic inspired a generation of filmmakers, including George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Christopher Nolan, who likened his film Interstellar (2015) to 2001.

Fifty years after its initial release, the film is getting renewed attention, including the debut of a new 70mm print at the Cannes Film Festival and a limited theatrical release beginning May 18.

Jay Telotte, professor of film studies in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech, explains why the legacy of the film endures:

This is a movie that came out 50 years ago. Why are we still talking about it?

It’s certainly the most influential of all science fiction films, and the most often referenced of all the films in the genre. And by referenced I don’t mean simply homages in other science fiction films, but across the whole cultural landscape. It’s entered into our vocabulary, as in such phrases as “Open the pod bay door, Hal,” or “I’m sorry, I can’t do that, Dave.” These are phrases that have become part of our common parlance. But more than that, this is a movie that has impacted the science fiction genre and how we make films.

How so?

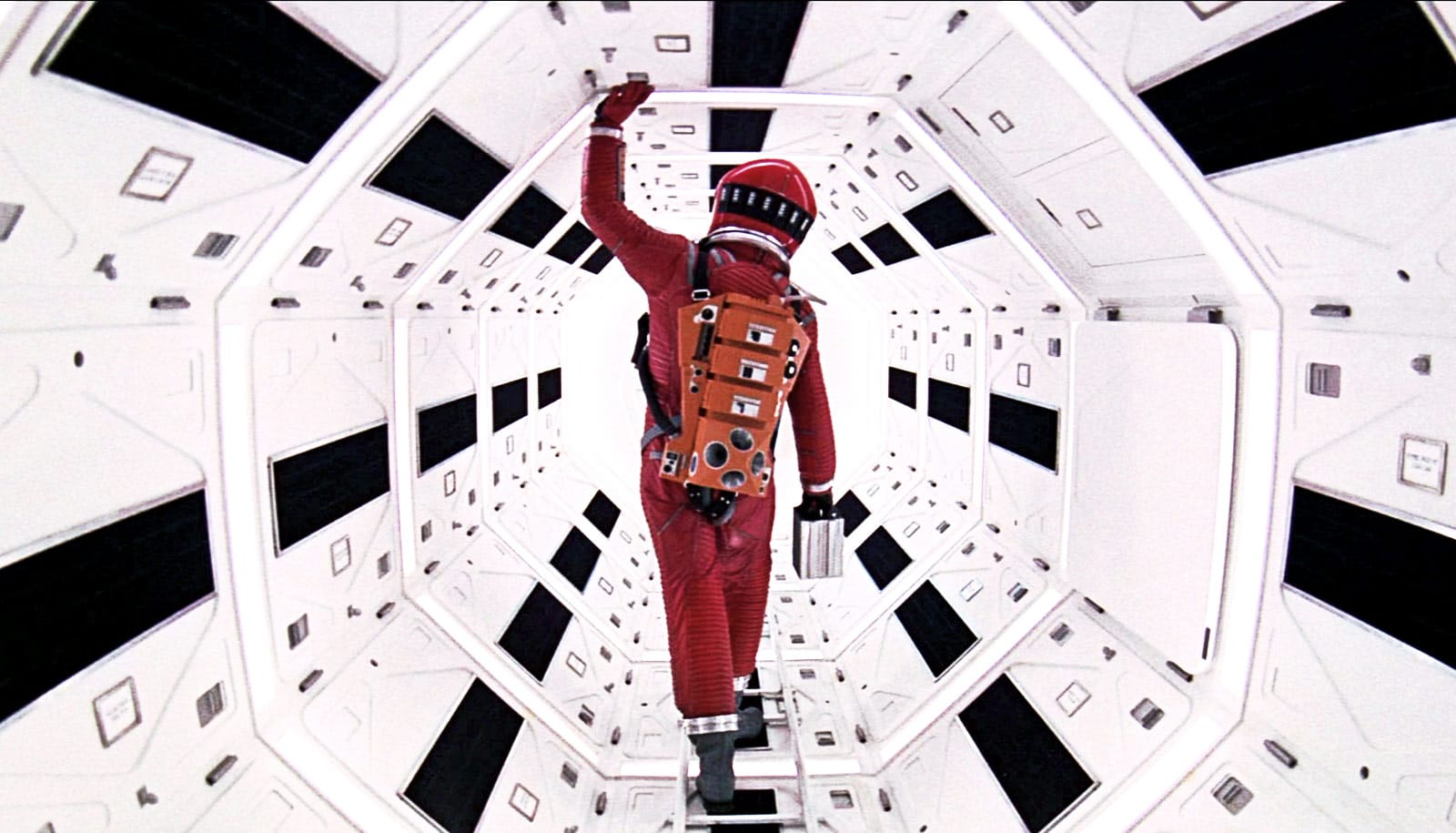

Kubrick invented or advanced a variety of new techniques, new ways of telling stories in film. For example, he made use of a complicated technique called front projection. He deployed a new process called slit-scan photography for the Stargate scene. He made use of what is maybe the best example of something called a match cut in all of film history. A match cut is where one cuts between two different shots that have the same kind of geometry.

The first sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey is called the Dawn of Man. It features apelike creatures who have touched the monolith, become inspired, and discovered tools. One learns to use a bone as a weapon to chase other groups of apes away from the watering hole, and then uses it to kill. Exulting, he throws the bone up in the sky and we watch as it drifts up and up and, suddenly, we’re in the darkness of space and there’s a space station, shaped like the bone, at the same angle as the bone. And of course, in space, we see that the US and Russia are still competing.

With this simple cut Kubrick has says, “We’ve gone from the Dawn of Man to 2001, yet how far have we really come? Not very far. We throw our bones a little higher in the sky, but we’re still doing the same violent things.” So, just with inspired editing, he is able to tell an enormously important story.

What impact did this film have on science fiction as a genre?

Well, obviously he made science fiction very respectable.

When he contacted the science fiction novelist Arthur C. Clarke and asked if they could work together on a project, Clarke asked, “What do you have in mind?” And Kubrick says, “Well, I want to make the proverbial good science fiction movie because no one’s ever done that.”

I think that comment was something of an overstatement, because there are some really fine science fiction films that appeared before 2001, such as Metropolis in 1927, Invasion of the Body Snatchers in 1956, and Forbidden Planet in 1956. But he did indeed make a really good one. He made one that raised the bar for everybody else.

Sixty years ago, the venerable British film journal Sight and Sound started doing a worldwide poll of film critics, directors, et cetera, who are central to the film industry, asking them to rank the ten greatest films of all time. For the longest time, it included only works such as Citizen Kane (1941), Renoir’s Rules of the Game (1939), The Seven Samurai (1954), Fellini’s 8 ½ (1963). In 2012, it ranked 2001 in sixth place. This means the critics now are looking back and saying science fiction has a place among the greatest films ever made. Kubrick raised the bar, and raised it recognizably amongst everybody who’s interested in film, not just science fiction fans.

How did this movie inspire other filmmakers?

Well, it set the bar so high that no one could do exactly that kind of film for a long time. It obviously was beyond much of the film industry’s capacity—most filmmakers’ technical abilities, and most filmmakers’ inspiration. It wasn’t until almost a decade later, in 1977, that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg would come along with the original Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind—both similarly ambitious but pointedly different efforts.

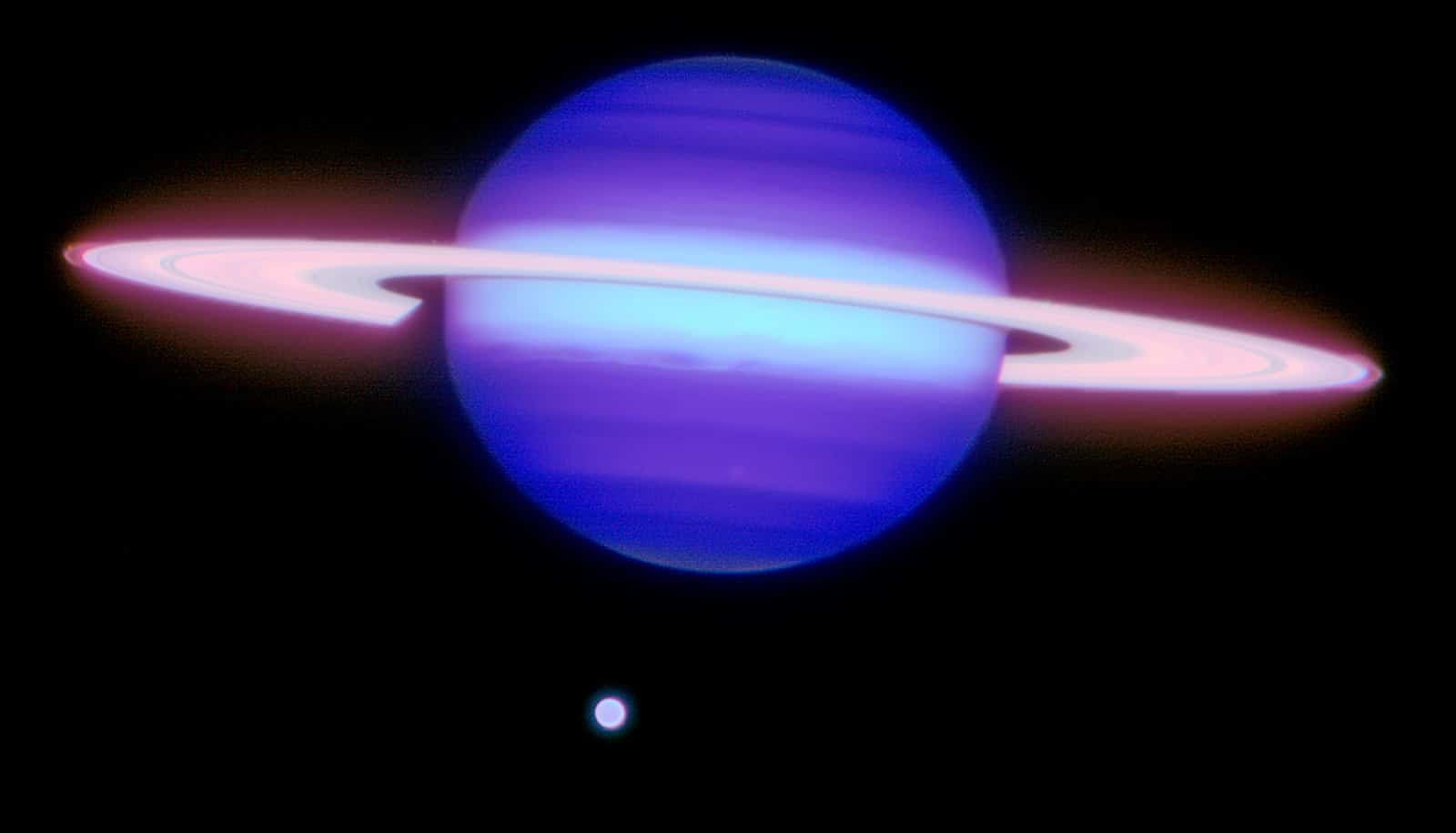

Lucas announced the new world of science fiction in the opening scene of Star Wars, which pays homage to 2001. While Kubrick’s film opened with an iconic image of the sun, the Earth, and the moon aligned in space, Lucas removed the middle planet and replaced it with a space battle. And that new opening effectively says, “All right, you remember 2001, but I’m going to take you to a little different place and mine’s going to be more about the ships and the people, this political conflict that’s going on, rather than a meditation on the evolution of humanity.”

One of the most recognizable images from 2001 is the glowing red eye of HAL, the astronauts’ virtual assistant who eventually turns into a murderer. Would this be the same movie without HAL?

I don’t want to say it’s essential but he made the right choice. He made so many right choices. It keeps viewers concentrated on that realm of cold logic that Kubrick wants us to change from, to move away from, or at least to interrogate.

We never see aliens in this film. Good choice?

Great choice.

It would have made us think about all the different aliens we had seen before in film. And it would make us think back to earlier visions of alien invasion and therefore alien threats.

The other option would have been depicting aliens as in something like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), which is still kind of an alien invasion film because it features a flying saucer that lands in Washington, but the guy who steps out is Michael Rennie, the English actor. He speaks with an English accent; he’s very calm and very nice. But the reason he’s here is because, as he says, “You people are messing up and we’re going to tell you how you should live your lives.” Where he’s from, they have turned everything over to robots, and the people know that if they don’t behave nicely to each other, the robots will punish them all.

How Frankenstein’s monster has shuffled through movies and comics

But Kubrick threw out the aliens and says, “Let’s make this about ourselves, only about ourselves, because we’re the ones who have to make those crucial decisions. We’re the ones who have to change our lives, not have it miraculously happen because somebody else comes in and tells us what to do, or because robots come in and force us to behave in a certain way, or because we have to fight against various three-headed monsters or blob-like invaders. This is our own problem.”

This choice of not showing aliens allows him to focus our attention on human evolution. Kubrick is putting the choice to us and saying humanity has to find ways to change, to become something better.

Even after five decades, it remains a notoriously difficult movie to interpret. What is it all about?

You’re not going to bind it up in a nutshell, but one element that stands out is that Kubrick is calling for humanity to emerge from the Age of Reason visualized in the final room in which we see an old David Bowman—and become something new. We need to move beyond that, and where we go is to what Kubrick might have termed imaginative man, man who follows his eyes, as he tries to take in a challenging world of new images and learns to use his imagination to overcome problems.

This is what the ancient Greeks had formulated for us long ago, that there is a logical side to humanity, as well as an emotional side to humanity, and that the imagination offered a way for bringing these two sides into harmony. I believe Kubrick was basically revisiting this notion and asking, “Might that still be a good path for us to follow?”

Source: Georgia Institute of Technology