Modifying a muscle transplant operation, a surgical team found a way to restore even smiles to the faces of patients dealing with birth defects, stroke, tumors, or Bell’s palsy.

“The smile has been judged as the most important sign to express positive emotions, and people are judged to be angry when they can’t smile,” says Kofi Boahene, associate professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery and dermatology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Previously, the best we could hope for most of the time with surgery was a smirk, where just the corners of the mouth upturn in a smile, like the one Mona Lisa has in DaVinci’s famous painting,” Boahene says. “But that isn’t a joyful, expressive smile where the lips move up, teeth show, and eyes narrow. Now we’re able to really restore a true smile.”

“In the past, we were restoring fake smiles and now our patients’ new smiles are so contagious that you can’t help but smile back.”

Standard surgical fixes for people with one-sided facial paralysis transplanted muscle tissue from a person’s thigh to pull up on the paralyzed side of the mouth. The modified procedure uses gracilis muscles from the thigh placed from the corner of the mouth or the upper lip to the cheek and eyelid to recreate an authentic smile that shows teeth and gum on both sides of the face.

The surgeons report their findings in JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, along with measure of improvement in 10 women and two men between 20 and 64.

One-sided facial paralysis creates social awkwardness and depression, making those who have it self-conscious about their appearance when speaking or eating in front of others, Boahene says. It also creates a tendency to drool and difficulty with normal blinking, which can cause dry and uncomfortable eyes.

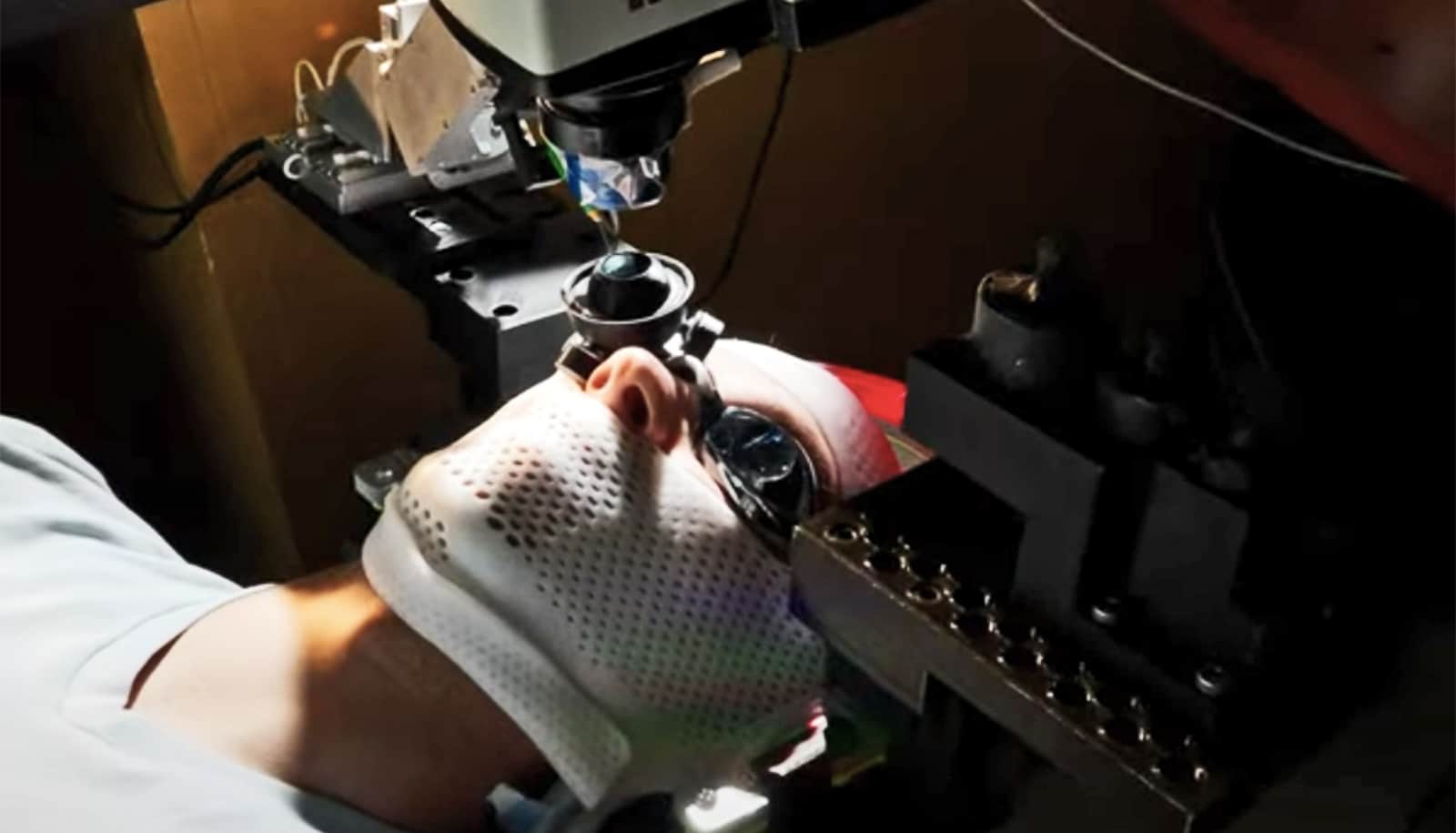

Prior to surgery, the physicians videoed and measured the type, angle, and degree of smile on the non-paralyzed side of the patients’ faces. During surgery, they positioned the new muscles so that they pulled the lips up to match the non-paralyzed half-smile when contracted. Then they rerouted blood vessels and one or more types of nerves to the transplanted tissue from the non-paralyzed side of the face.

The idea was that when the nerves on the non-paralyzed side send a signal for the muscle to contract, forming a smile, they do so for the paralyzed side of the face, too, Boahene says.

By four months after the procedure, all participants had function in the transplanted muscle. On average, each showed an extra three teeth when smiling on the newly functional side of their face. Gum exposed during smiling increased from an average of 31.5 millimeters before surgery to 43.7 millimeters after. Wrinkling around the eyes when smiling was observable in four of the patients. The surgeons also say asymmetry, or differences between the corners of each side of the mouth, went from an average of 9.1 millimeters to 4.5 millimeters after surgery in the patients, making their smiles more even.

The right smile could boost trust and giving

According to Boahene, some people come to see him soon after their paralysis, and others after they have exhausted all options, such as rehabilitation.

“For me, joy is to see a child who has never smiled or someone who has lost their smile to paralysis be able to smile; you just see people transform,” he says. “In the past, we were restoring fake smiles and now our patients’ new smiles are so contagious that you can’t help but smile back.”

Insurance usually covers the procedure as a functional, reconstructive surgery. But in cases that aren’t covered, the cost of the procedure would be around that of a new single family home.

Most people with facial paralysis, no matter how long they have been paralyzed, are candidates for the procedure. Patients with a weak gracilis muscle can use alternative muscles instead.

Additional authors of the study came from Johns Hopkins; Mid-Atlantic Permanente Medical Group; the University of California, Los Angeles; and Ohio State University.

Source: Johns Hopkins University