There’s a new way to harvest a key ingredient responsible for making sunscreen more environmentally friendly.

By pushing the discovery to commercialization, researchers hope to make “green” sunscreens more available, reducing dependence on oxybenzone- and octinoxate-based sunscreens. These harmful chemicals accumulate in aquatic environments; they’re toxic to marine life and potentially disrupt the human reproductive system.

The researchers found a more efficient way to harvest the UV-absorbing amino acid known as shinorine, which marine organisms like cyanobacteria and macroalgae produce. The conventional method extracts shinorine from red algae, which takes as long as a year to grow and has a long processing time.

The new method reduces harvesting time to less than two weeks. Principal investigator Yousong Ding, an assistant professor of medicinal chemistry at the University of Florida College of Pharmacy, and his colleagues have brought production out of the wild and into the laboratory, where they have much more control.

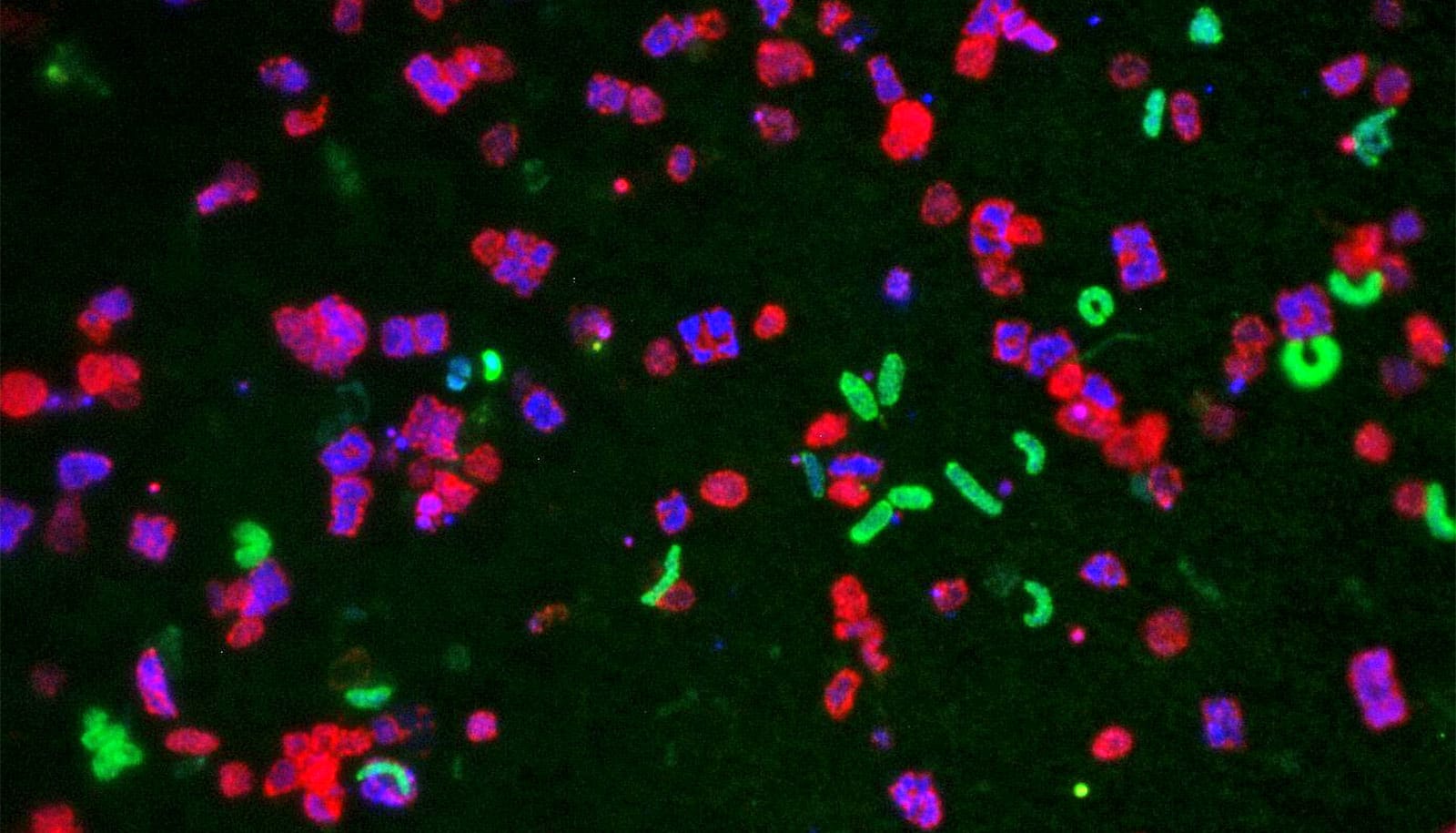

Researchers selected a strain of freshwater cyanobacteria, Synechocystis, as a host cell for shinorine expression because it grows quickly, and it’s easy for scientists to modify its genes. Next, they mined the genes responsible for the synthesis of shinorine from a native producer, the filamentous cyanobacterium Fischerella.

The researchers inserted these genes into Synechocystis. Using this method, they produced 2.37 milligrams of shinorine per gram of cyanobacteria, which is comparable to the conventional method’s yield.

“This is the first time anyone has demonstrated the ability to photosynthetically overproduce shinorine,” Ding says.

New sunscreen won’t seep into the skin

The production method researchers discovered has broader applications for the production of other known cyanobacterial products and could expedite the process of turning cyanobacterial genomes into potential new drugs.

Researchers secondarily confirmed that the shinorine they harvested through the new method protects cells from UV rays.

To test this, they exposed shinorine-making cells to UV radiation. Control cells that do not produce shinorine experienced an obvious decline in population from UV-B exposure. In the other cells, shinorine acted as sunscreen against UV-B light, which helped the cells live and grow better.

The findings appear in ACS Synthetic Biology.

Source: University of Florida