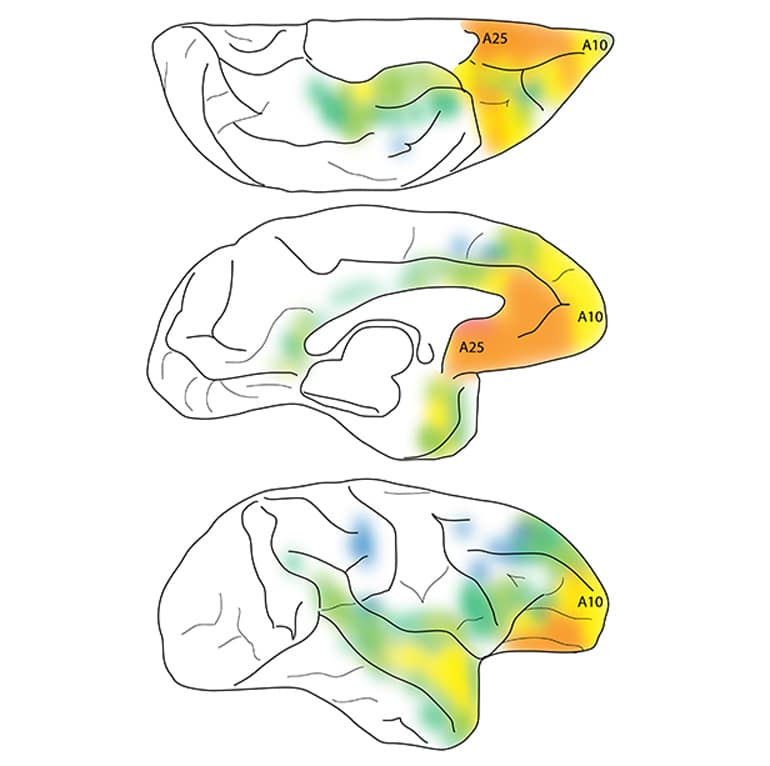

A new, finely detailed map depicts the neural pathways leading to and from the “sadness center” of the brains of nonhuman primates.

In the early 1900s, German neurologist Korbinian Brodmann began to study the architecture of the human brain. He divvied up the cerebral cortex—the outer, convoluted brain region that plays a key role in higher functions like memory, attention, and consciousness—into 52 distinct regions.

One of these, a thin sliver of tissue buried deep inside, became known as Brodmann area 25. More colloquially, it’s known as the brain’s “sadness center.”

“When somebody is transiently sad for a reason, let’s say something happened to a family member or a friend, it’s normal to be sad, and this area lights up,” says neuroscientist Helen Barbas, professor of health sciences at Boston University Sargent College and faculty member of the Graduate Program in Neuroscience. “But in people who are depressed, this area stays active. It’s on all the time.”

This work, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, shows strong connections between area 25 and other regions involved in emotional regulation, memory, internal states, and stress response. Barbas and student Mary Kate Joyce also found a moderate connection between area 25 and frontopolar area 10, a part of the brain that helps regulate emotions and is smaller in humans with major depression.

While these findings represent preliminary work in nonhuman primates, they suggest that strengthening the link between these two areas may offer a possible target for treating chronic depression.

“This is an area that people may look at for some kind of therapeutic intervention, and it doesn’t have to just be drugs. It could be activating the frontopolar area 10 noninvasively, maybe using transcranial magnetic stimulation,” says Barbas. She notes that neurologists have used deep brain stimulation in area 25 to treat drug-resistant depression, and suggests that frontopolar area 10’s location closer to the brain’s surface may make it an easier target for such treatment.

To create their map, Barbas and Joyce injected four tracers of different colors and characteristics in primate area 25. The brain cells at the site of injection absorbed the tracers into their cell bodies, then sent them down their long axons to their branching endpoints in other areas. The brain cells absorbed other tracers backward, through axons at the injection site, into the parent cell bodies.

Neurotic? Two other traits may shield your mental health

The experiment allowed researchers to see which areas receive signals from area 25, which areas send signals to area 25, and which circuits looped both ways. The scientists then fed that information into computational analyses to measure the strength and patterns of the connections.

“The pattern of connection is very important,” says Barbas. Area 25 “acts sort of like a feedback system” to most cortical areas, she says. However, it feeds signals forward to certain memory-related areas, like some near the hippocampus. “That means area 25 is probably triggering personal memories through those areas,” she says.

The most surprising finding was the moderate connection between area 25 and frontopolar area 10, a region best known for juggling complex working memory tasks, but one that also seems to regulate emotions in humans. “We think that it may help modulate area 25, exercise some kind of control,” says Barbas. “So this is why it’s relevant.”

The National Institutes of Health funds this work.

Source: Boston University