Ring-tailed lemurs, primate cousins that live in groups of up to two dozen on the island of Madagascar, have distinct personalities that drive their social behavior, a new study of group dynamics suggests.

“…social connectedness influences health, immunity, survival. This is true for animals as well as humans.”

First author Ipek Kulahci spent several years studying ring-tailed lemurs at the Duke Lemur Center in North Carolina and the St. Catherines Island Lemur Program in Georgia.

Along the way, she noticed a lot of variation in social behavior from one lemur the next: Fern is a socialite, Captain Lee a loner, and Limerick and Herodotus are best buddies.

Some individuals seemed more outgoing than others. To try to quantify that, she followed four groups of ring-tailed lemurs over two consecutive years and recorded their behavior a minimum of four times a week for at least two months.

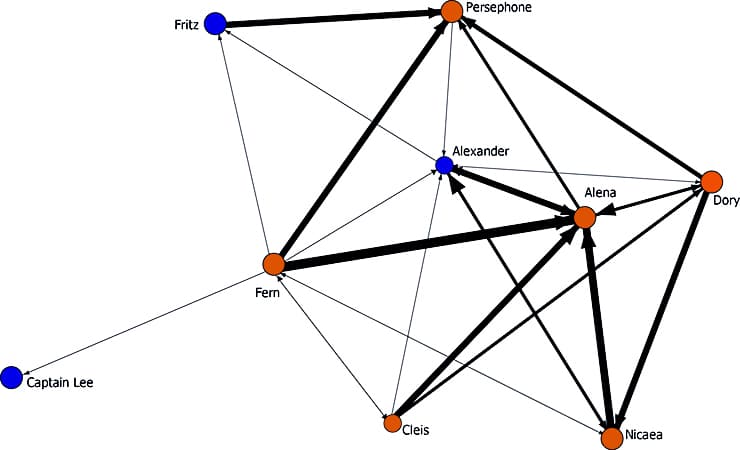

Using a method called social network analysis, she was able to measure how many connections each lemur had, with whom, and how strong those connections were. She was also able to figure out which lemurs were most influential in each group—either because they connected others, or because they had well-connected friends.

Kulahci and colleagues found that lemurs behaved consistently no matter what their age, sex, or social situation. Some lemurs like Fern tended to seek connection; reinforcing social bonds by frequently picking through their friends’ fur and responding to other lemurs’ calls and scent marks.

Their interactions weren’t always amicable—the more socially active lemurs were also more likely to chase others or pick fights with individuals with whom they weren’t on friendly terms.

“But they have a drive to interact with others, rather than be a loner,” says Kulahci, now a postdoctoral researcher at University College Cork in Ireland.

Lemurs share gut bacteria when they cuddle

The researchers also found that lemurs, like us, don’t bond with just anyone. Whether they are extroverted or shy, all lemurs have an inner circle of groupmates they tended to groom, call back, or otherwise keep in touch with more than others.

“They essentially have buddies,” Kulahci says.

“This is important because social connectedness influences health, immunity, survival,” Kulahci says. “This is true for animals as well as humans.”

Researchers from Princeton University are coauthors of the study, which appears in Animal Behaviour. The Animal Behavior Society, American Society of Mammalogists, American Society of Primatologists, and Princeton University funded the work.

Source: Duke University