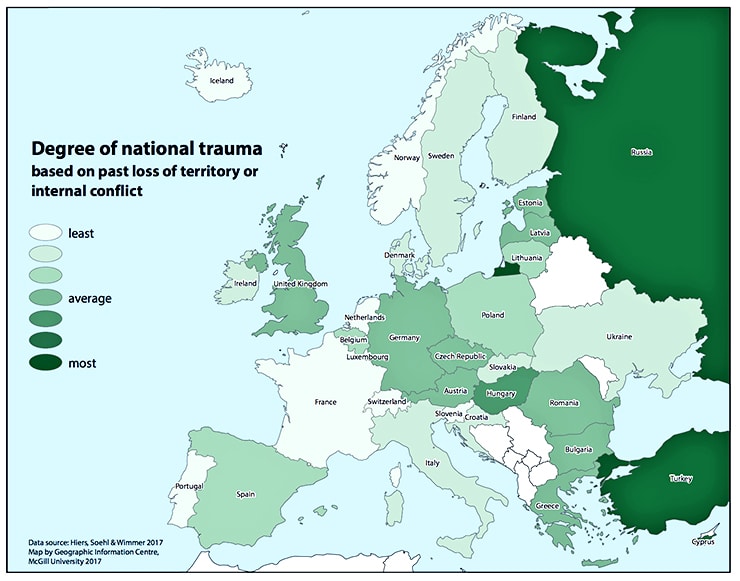

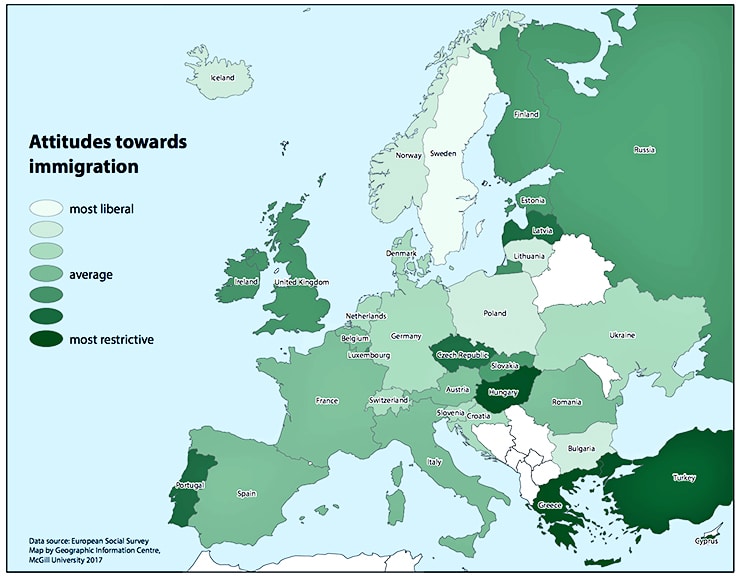

The European countries that tend to be most hostile towards immigrants have lost territory or sovereignty or experienced a history of conflict, a new study suggests.

In these nations, prior traumatic experiences have led to the growth of a more ethnically-based nationalist narrative of “us” and “them” that makes accepting immigrants of different origins today more difficult, researchers report.

The researchers came to their conclusion after looking at varying ways to explain the differing degrees of anti-immigrant sentiment in 33 European countries. Think of Italy, the Netherlands, and Sweden and then compare attitudes towards immigrants in those countries with those in Great Britain, Hungary, or Greece, and you get the idea.

‘As if history didn’t matter’

“Whatever their focus, people who write about this subject have mainly looked at the issue through the lens of present conditions, as if national histories didn’t matter,” says Thomas Soehl, who teaches sociology at McGill University.

“What we argue is that although various contemporary factors at an individual or national level may influence anti-immigration sentiment, a country’s prior experience of internal or external conflict plays an important role in shaping the kind of nationalism which exists there. And that the style and intensity of nationalism that develops as a result influences contemporary attitudes towards immigrants.”

To arrive at this conclusion, researchers first developed a geopolitical threat score (GPT) for each of the 33 European nations they studied. They based the score on the history of internal and external conflict as well as the loss of territory or sovereignty in each country since the modern nation-state came into being.

This score reflects, in other words, how much the past history was marked by traumatic losses or the realistic threat of such losses. They then looked at how the GPT score in each nation was correlated with the degree of anti-immigrant sentiment.

“It is the period since a country first appeared on modern geopolitical maps that is most influential when it comes to developing nationalist narratives,” says Andreas Wimmer, who teaches sociology at Columbia University and is one of the authors of the study.

“Using this as the starting point of collective memories we then looked at whether during, or after, the transition to the nation-state a country experienced losses of both territory and independence as well as recurrent, ongoing external and internal conflicts.”

Testing the theory

The researchers tested the validity of their theory by looking at attitudes towards immigrants as they were reflected in survey results from the European Social Survey over various years in the first decade of the 21st century. The surveys included questions about people’s attitudes towards potential immigrants whose race or ethnic ancestry differed from the majority in the host country.

Europeans say they’d accept more refugees with fairer system

The researchers discovered that, within each country, attitudes towards immigrants of other races and ethnic groups remained very consistent over time. More importantly, when they started looking at the way that people in differing countries responded to the survey questions about taking in immigrants of different races, they could see a clear correlation with where that country stood along the GPT scale.

“In countries with a GPT score of zero (with no loss of territory or sovereignty, or recurrent conflict in their past) we found that nearly two-thirds of the citizens would respond by being willing to allow many or some immigrants of different racial or ethnic origins,” says Wesley Hiers, who teaches in the sociology department at the University of Pittsburgh.

He adds: “At a GPT of 2, which is about average, we found that just below half of the citizens (or 48 per cent) were willing to allow many or some immigrants to come.” And at a GPT score of 6 (which is the highest threat score) the researchers found that only just over a quarter of the citizens would allow some or many immigrants into the country.

“And these numbers held true,” he continues, “even once we looked at the effects of other factors, such as rural/urban divide, religiosity, level of education, levels of contemporary immigration, unemployment, and so on.

“All of this makes us believe that we are on the right track when we argue that past geopolitical competition and war, and losses of territory and sovereignty shape current attitudes towards immigrants in Europe. It will be important to see how well this argument travels to other contexts such as Latin America.”

Why some 19th century immigrants went back to Europe

The researchers report their findings in the journal Social Forces.

Source: McGill University