Researchers have found two previously unknown phyla of bacteria inside the mouths of dolphins.

A phylum is a broad taxonomic rank that groups together organisms that share a set of common characteristics due to common ancestry.

The discovery of two bacterial phyla, as well as additional novel genes and predicted products, provides new insights into bacterial diversity, dolphin health, and the unique nature of marine mammals in general, says David Relman, professor of medicine and of microbiology and immunology at the Stanford University School of Medicine and senior author of a new paper describing the findings.

Bacterial ‘gold’

The US Navy’s Marine Mammal Program reached out to Relman more than 10 years ago for help in keeping its dolphins healthy. The animals are highly trained and perform missions at sea.

“We knew there was gold in those dolphin mouths, and we decided it was time to go after it…”

Previous research by Relman’s group, in collaboration with the Marine Mammal Center, revealed a surprising number of never-before-seen bacteria in dolphin and other marine mammal samples, particularly those swabbed from the dolphins’ mouths, says Relman. Some of the bacteria found in the current study are affiliated with poorly understood branches of the bacterial tree.

“These organisms, about which we have known just a tiny bit, are basically the dark matter of the biological world,” he says. “We knew there was gold in those dolphin mouths, and we decided it was time to go after it with more comprehensive methods.”

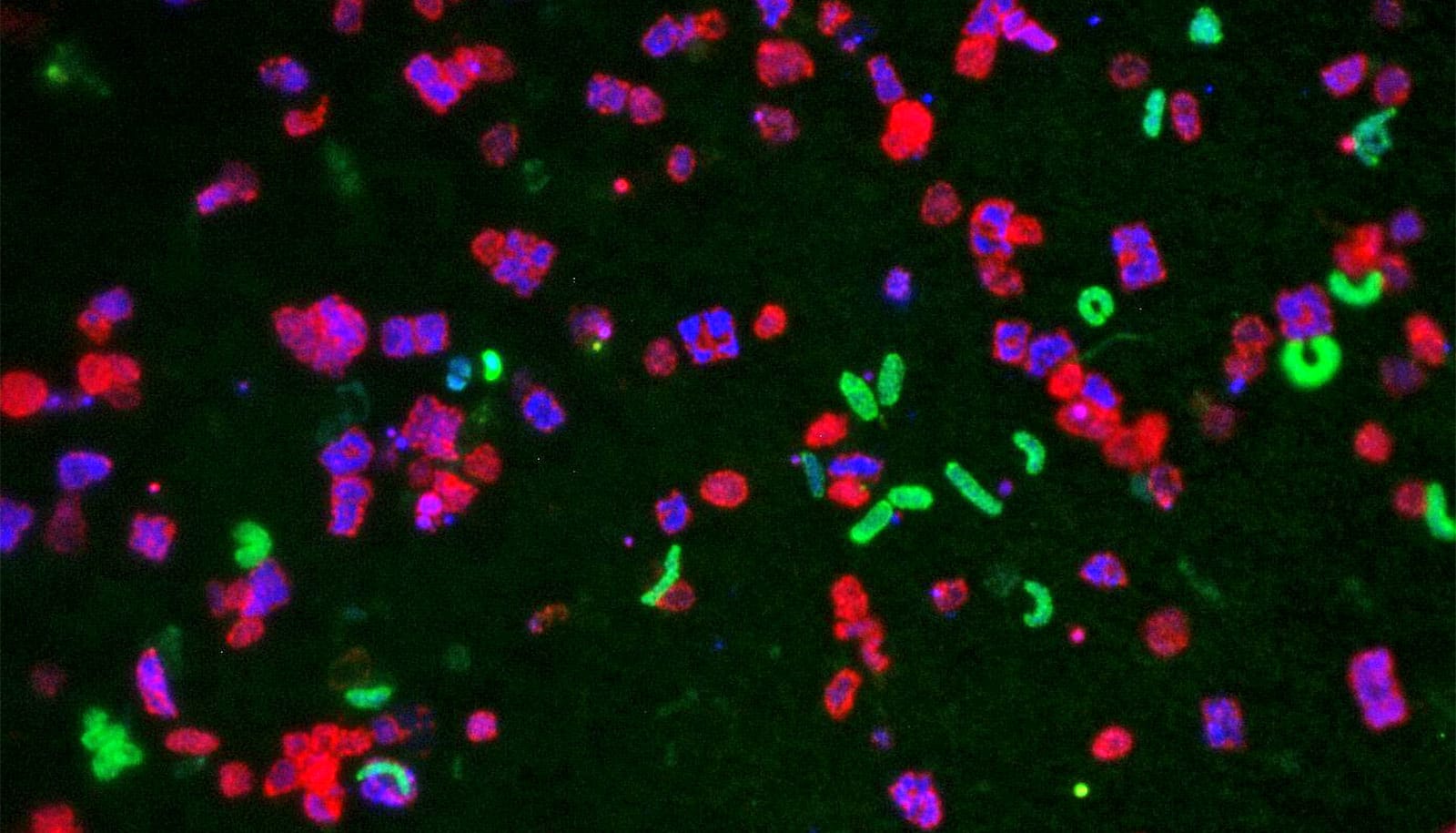

In the new study, the researchers identified bacterial lineages by reconstructing their genomes from short bits of DNA. The genome of a given cell serves as its blueprint and contains all its operating instructions, encoded in DNA.

The researchers named one of the newly identified lineages Delphibacteria in honor of the dolphins (Delphinidae is the Latin name for oceanic dolphins).

Earth may be home to 1 trillion species of microbes

By looking at the genes encoded in the genomes of Delphibacteria representatives, the researchers gained insight into the bacteria’s lifestyle.

Researchers predict the bacteria express a property called denitrification that may affect dolphins’ oral health: The chemical process can cause inflammation and could be connected to gum disease. Denitrification also occurs in plaque on human teeth, suggesting that something about mammalian mouths selects for this process.

Putting the puzzle together

The researchers differentiated between bacteria and predicted their behavior by looking broadly at their genomes.

“What we do first is shear the DNA into a bunch of little bits and pieces, the mix of DNA is sequenced, and we then try to figure out how the genomes were originally assembled,” says lead author Natasha Dudek, a graduate student at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

If a gene is one piece of a puzzle, the researchers put together the whole puzzle.

“Typically, people are interested in small Cas9 proteins that might be easy to manipulate and deliver into cells,” says Relman. “These are the opposite—they’re enormously big.”

Different structures in the genes that encode these proteins account for the size difference, and the researchers suggest these large Cas9 proteins have different properties from those known before. Dudek plans to pursue this line of research further.

‘Competing’ ocean bacteria may collaborate instead

The study also feeds nicely into ongoing work in Relman’s lab. A large, comparative study is underway to investigate how adaptation to life in the sea might affect marine mammal microbiomes. Beyond discovering and characterizing novel bacteria, Relman wants to apply his research to conservation.

“Marine mammals are becoming increasingly endangered,” he says. “They are sentinel species for the health of the sea, and the more we can understand their biology, the better we can anticipate changes in the health of their environment.”

The researchers report their findings in Current Biology.

Additional researchers from the UC Berkeley, UC Santa Cruz, and Stanford also contributed to the study. The Office of Naval Research supported the study, as did Stanford’s medicine and microbiology and immunology departments.

Source: Nicoletta Lanese for Stanford University