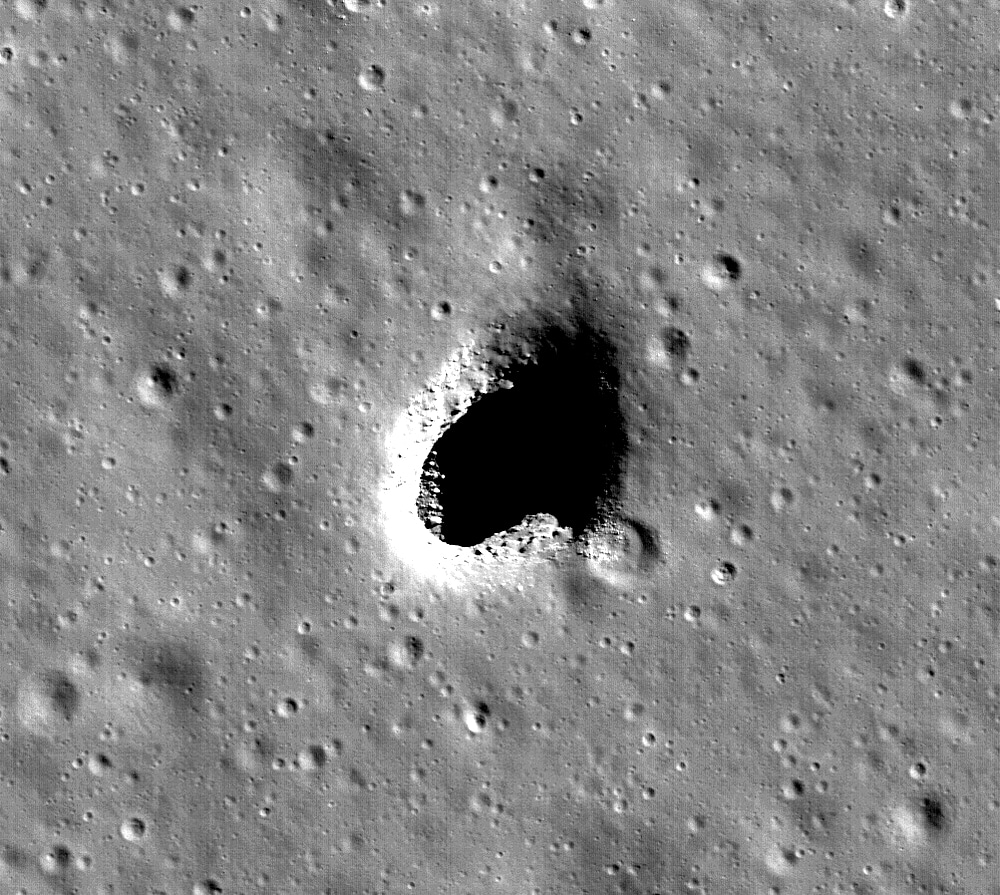

A large open lava tube in the Marius Hills region of the moon could protect astronauts from hazardous conditions on the surface.

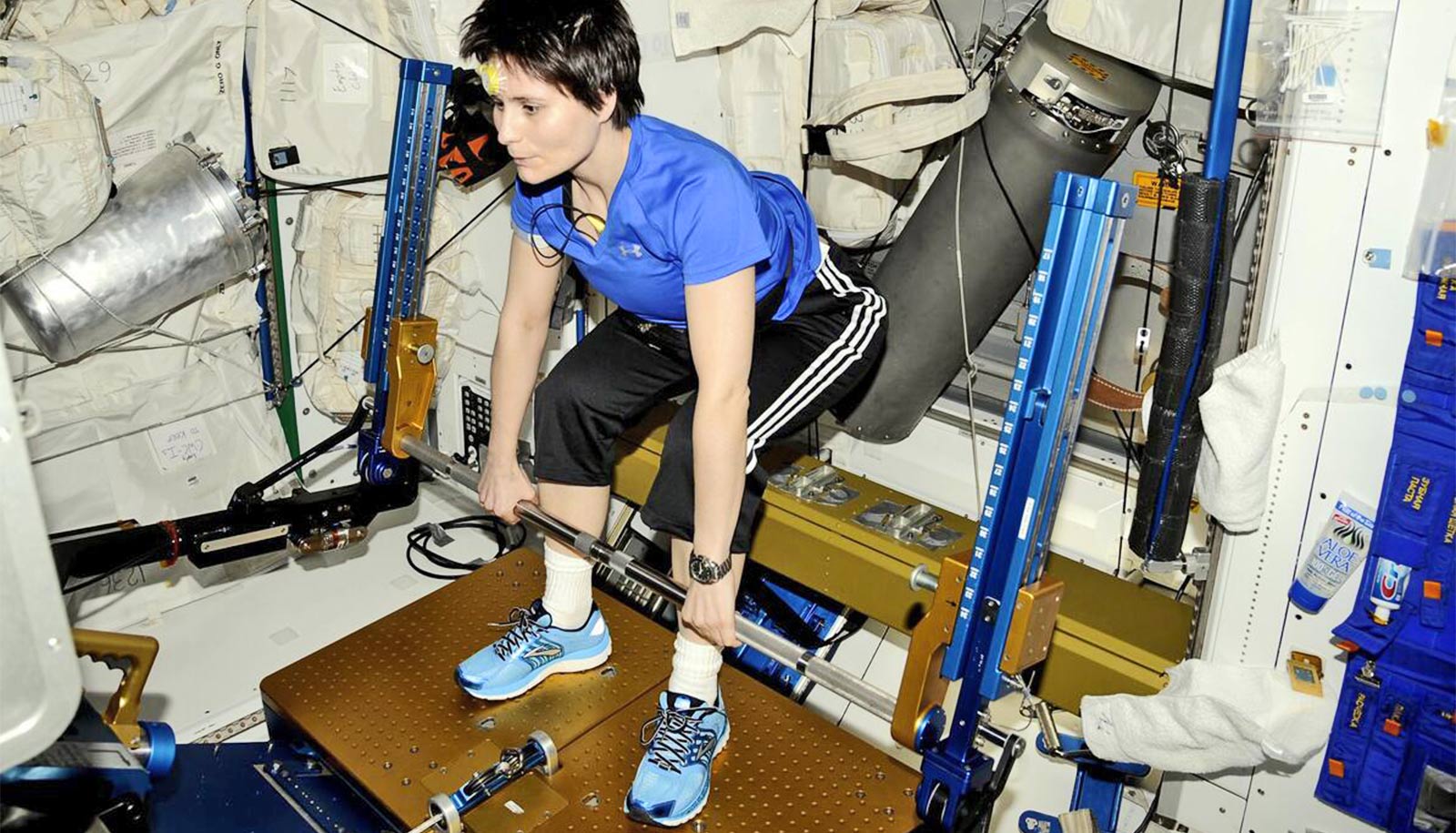

No one has ever been on the moon longer than three days, largely because space suits alone can’t shield astronauts from its elements: extreme temperature variation, radiation, and meteorite impacts.

Unlike Earth, the moon has no atmosphere or magnetic field to protects its inhabitants, and scientists say the safest place to seek shelter is the inside of one of these tubes.

Lava tubes are naturally occurring channels formed when a lava flow develops a hard crust, which thickens and forms a roof above the still-flowing lava stream. Once the lava stops flowing, the tunnel sometimes drains, forming a hollow void.

“It’s important to know where and how big lunar lava tubes are if we’re ever going to construct a lunar base,” says Junichi Haruyama, a senior researcher at JAXA, Japan’s space agency.

“But knowing these things is also important for basic science. We might get new types of rock samples, heat flow data, and lunar quake observation data.”

JAXA analyzed radar data from the SELENE spacecraft to detect underlying lava tubes. Near an entrance to the tube called the Marius Hills Skylight, they found a distinctive echo pattern: a decrease in echo power followed by a large second echo peak, which they believe is evidence of a tube.

The two echoes correspond to radar reflections from the moon’s surface and the floor and ceiling of the open tube. The team found similar echo patterns at several locations around the hole, indicating there may be more than one.

SELENE’s radar system wasn’t designed to detect lava tubes—it was built to study the origins of the moon and its geologic evolution. For these reasons, it didn’t fly close enough to the moon’s surface to get extremely accurate information on what is (or isn’t) underneath.

When the JAXA team decided to use their data to try and find lava tubes, they consulted scientists from the GRAIL mission, a NASA effort to collect high-quality data on the moon’s gravitational field.

By surveying the areas where GRAIL had identified mass deficits, or less mass under the surface, they narrowed down the data they needed to analyze.

“They knew about the skylight in the Marius Hills, but they didn’t have any idea how far that underground cavity might have gone,” says Jay Melosh, a GRAIL co-investigator and professor of earth, atmospheric, and planetary sciences at Purdue University.

“Our group…used the gravity data over that area to infer that the opening was part of a larger system. By using this complimentary technique of radar, they were able to figure out how deep and high the cavities are.”

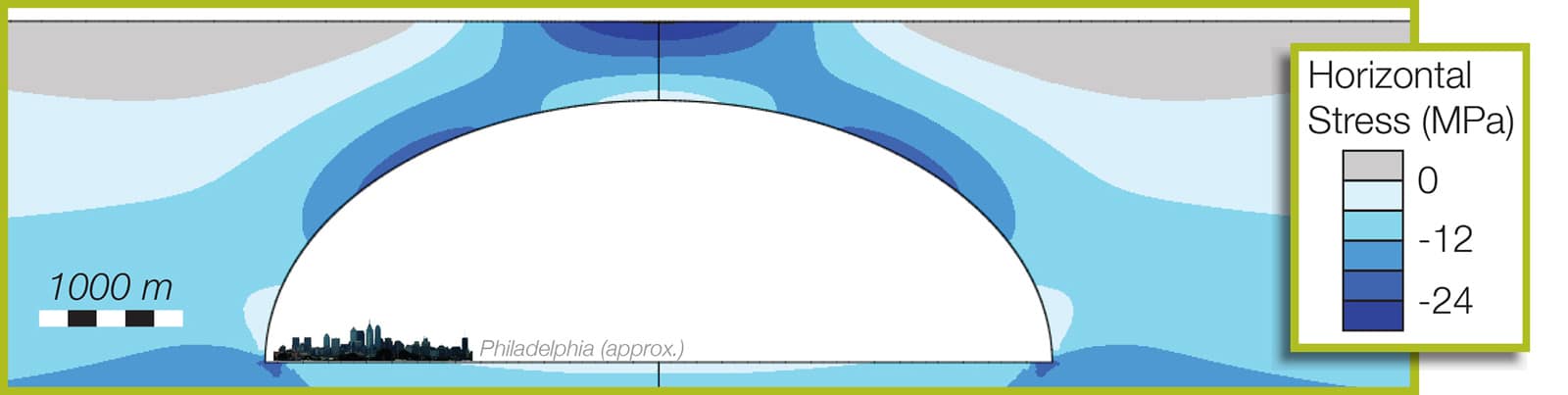

Lava tubes exist on Earth, but the ones on the moon are much larger.

For a lava tube to be detectable by gravity data, it needs to extend several kilometers in length and at least one kilometer in height and width—which means the lava tube near the Marius Hills is spacious enough to house one of the largest US cities—if the gravity results are correct.

Map shows water ‘nearly everywhere’ in moon soil

The existence of lava tubes on the moon has been the subject of speculation in the past, but this combination of radar and gravity data provides the clearest picture of what they look like and how big they are yet.

The information might be more useful than previously expected.

At the first meeting of the National Space Council in decades, Vice President Mike Pence announced that the Trump administration will redirect America’s focus in space to the moon—a fundamental change for NASA, which abandoned plans to send people to the moon in favor of Mars under President Obama.

“We will return NASA astronauts to the moon—not only to leave behind footprints and flags, but to build the foundation we need to send Americans to Mars and beyond,” he said.

The findings appear in Geophysical Research Letters.

Source: Purdue University