Tree height may be key to spotted owl conservation, say researchers. And that could be good news for forests.

“This is a way to protect more large tree habitat, which is what the owls want…”

For 25 years, many forests in the western United States have been managed to protect habitat for endangered and threatened spotted owls. A central tenet of that management has been to promote and retain more than 70 percent of the forest canopy cover. However, dense levels of canopy cover leave forests prone to wildfires and can lead to large tree mortality during droughts.

In a new study, however, scientists found that cover in tall trees is the key habitat requirement for spotted owl—not total canopy cover. It indicated that spotted owls largely avoid cover created by stands of shorter trees.

“This could fundamentally resolve the management problem because it would allow for reducing small tree density, through fire and thinning,” says lead author Malcolm North, a research forest ecologist with the University of California, Davis, John Muir Institute of the Environment and the USDA Pacific Southwest Research Station.

“We’ve been losing the large trees, particularly in these extreme wildfire and high drought-mortality events. This is a way to protect more large tree habitat, which is what the owls want, in a way that makes the forest more resilient to these increasing stressors that are becoming more intense with climate change,” North explains.

The previous tree canopy guidelines were largely drawn from past studies showing that spotted owls were more prevalent in forests with 70 percent or higher tree canopy cover. But those studies could not distinguish whether the presence of tall trees or high canopy cover were more important to the owl.

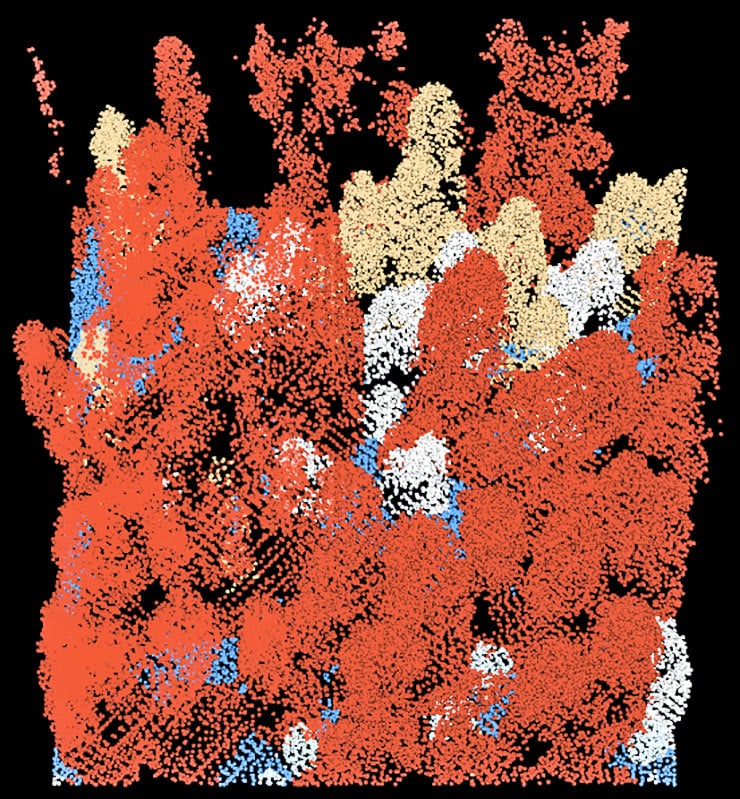

For this study, scientists used the relatively new technology of Light Detection and Ranging imaging, or LiDAR. The tool uses laser pulses shot from an instrument mounted in an airplane to measure a forest’s canopy in detail. The study’s authors used it to measure the height and distribution of tree foliage and forest gaps across 1.2 million acres of California’s Sierra Nevada forests.

“Field-based studies of forests are expensive and time-consuming, which means that measurements are generally taken over areas a fraction of an acre,” says coauthor Van R. Kane, an assistant research professor in the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences at the University of Washington. “We believe this is the largest spotted owl study yet in terms of the area of forest examined.”

Forest fires have changed a lot in 400 years

The authors also used a data set collected by wildlife researchers spanning more than two decades that recorded the positions of 316 owl nests in three national forests and Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks.

They found the owls seek out forests with unusually high concentrations of tall trees measuring at least 105 feet tall but preferably taller than 157 feet. These tall trees also tended to be areas with high levels of canopy cover. However, the owls appeared to be indifferent to areas with dense canopy cover from medium-height trees and avoided areas with high cover in short (less than 52 feet tall) trees.

“The analysis helps change the perception of what is important for owls—the canopy of tall trees rather than understory trees,” says coauthor and spotted owl expert R.J. Guitiérrez, a professor emeritus at the University of Minnesota. “The results do not mean a forest should be devoid of smaller trees because owls actually use some of those smaller trees for roosting. But it suggests a high density of small trees is likely not necessary to support spotted owls.”

How to find where bigger owls threaten little ones

Additional coauthors of the study are from the USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station, the University of Washington, Stanford University, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the US Forest Service Region 5 Remote Sensing Laboratory, the University of Minnesota, Tahoe National Forest, and UC Davis.

The USDA Forest Service funded the data analysis. The David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the US National Park Service funded the Carnegie Airborne Observatory data collection and processing.

The researchers report their findings in the journal Forest Ecology and Management.

Source: University of Washington, UC Davis