New research into frogs contradicts scientific assumptions about the evolution and diversification of species as they colonize different environments.

Evolutionary biologists long have supposed that when species colonize new geographic regions they often develop new traits and adaptations to deal with their fresh surroundings. They branch from their ancestors and multiply in numbers of species.

Not so for “true frogs,” the research indicates. The frog family scientists call Ranidae are found nearly everywhere in the world, and their family includes familiar amphibians like the American Bullfrog and the European common frog.

The research suggests, in contrast to expectations, “the rapid global range expansion of true frogs was not associated with increased net-diversification.”

“First, we had to identify where these true frogs came from and when they started their dispersal all over the world,” says lead author Chan Kin Onn, a doctoral student at the University of Kansas’s Biodiversity Institute.

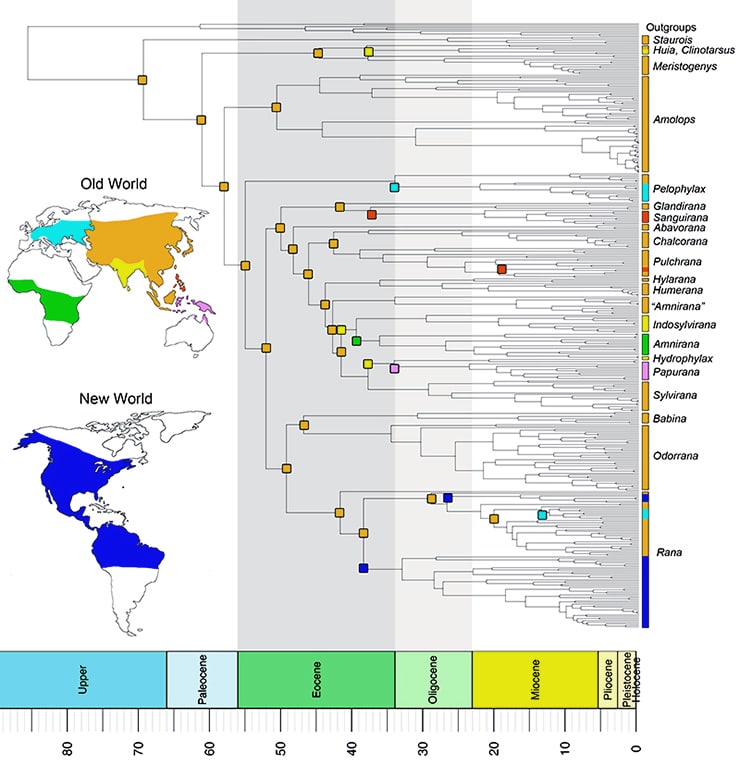

“We found a distinct pattern. The origin of these frogs was Indochina—on the map today, it’s most of mainland Asia, including Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Burma. True frogs dispersed throughout every continent except Antarctica from there. That’s not a new idea. But we found that a lot of this dispersal happened during a short period of time—it was during the late Eocene, about 40 million years ago. That hadn’t really been identified, until now.”

Next, Chan and coauthor Rafe Brown, curator-in-charge of the Biodiversity Institute’s Herpetology Division, looked to see if this rapid dispersal of true frogs worldwide triggered a matching eruption of speciation.

“We mined all of these sequences and combined them into a giant analysis of the whole family…”

“That was our expectation,” Chan says. “We thought they’d take off into all this new habitat and resources, with no competition—and boom, you’d have a lot of new species. But we found the exact opposite was true. In most of the groups, nothing happened. There was no increase in speciation. In one of the groups, diversification significantly slowed down. That was the reverse of what was expected.”

To establish the actual timing of true frogs’ diversification, Chan and Brown performed phylogenetic analysis of 402 genetic samples obtained from an online database called GenBank. These samples represented 292 of the known 380 true frog species in the world.

“We mined all of these sequences and combined them into a giant analysis of the whole family,” Chain says. “It is to my knowledge the most comprehensive Ranidae phylogenetic analysis ever performed that included most of the representative species from the family.”

Chan and Brown focused on four genes that would help to establish the family tree of true frogs.

“It’s a genealogical pedigree of specimens, a family tree of species,” Chan says. “Normally, you think of family tree as everyone in one family and how the various people are related. But this is more expanded where we look at how species are related to each other, so you can trace ancestry back in time.”

After completing the phylogenetic analysis, the researchers used several frog fossils to “time calibrate” the history of the frogs’ global dispersal.

More than heat determines where wood frogs survive

“We use fossil frogs because we can accurately date the fossils,” Chan says. “We know we found the fossil in a certain rock deposit, and we know with confidence how old the deposit is, so then we can estimate the age of the fossil.”

After Chan and Brown deduced similarities between fossilized true frogs as reported by paleontologists and contemporary true frogs, they placed fossils into groups of closely related species, which scientists call genera.

“Using data from paleontological studies, we can loosely place a fossil where in the phylogeny it belongs and can put a time stamp on that point,” Chan says. “That’s where calibration happens, each fossil is sort of like an anchor point. You can imagine with a really big phylogeny, the more anchor points or calibration points the better your time estimate.”

Through this process, the researchers concluded true frogs didn’t become one of the most biodiverse frog families due to dispersing into new ranges, or due to filling a gap created by a catastrophic die-off (such as the Eocene-Oligocene Extinction Event that triggered widespread extinctions from marine invertebrates to mammals in Asia and Europe).

After dinosaur extinction, frogs hopped to it

Rather, the rich diversity of species in the Ranidae family comes from millions of years’ worth of continual evolution influenced by a host of different environs.

“Our conclusion is kind of anticlimactic, but it’s cool because it goes against expectations,” Chan says. “We show the reason for species richness was just a really steady accumulation of species through time—there wasn’t a big event that caused this family to diversify like crazy.”

The paper appears in Royal Society Biology Letters.

Source: University of Kansas