Researchers have found an explanation for certain galaxies’ long period of rapid star formation.

In the early universe, brilliant starburst galaxies converted vast stores of hydrogen gas into new stars at a furious pace.

The energy from this vigorous star formation took its toll on many young galaxies, blasting away much of their hydrogen gas, tamping down future star formation. For reasons that remained unclear until now, other young galaxies were somehow able to retain their youthful star-forming power long after similar galaxies settled into middle age.

Shedding light on this mystery, Ted Bergin, an astronomer at the University of Michigan, and his colleagues used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, to study six distant starburst galaxies. They discovered that five of them are surrounded by turbulent reservoirs of hydrogen gas, the fuel for future star formation.

These star-forming “fuel tanks” were uncovered by the discovery of extensive regions of carbon hydride molecules in and around the galaxies. Carbon hydride is an ion of the CH molecule and it traces highly turbulent regions in galaxies that are teeming with hydrogen gas.

“Our results challenge the theory of galaxy evolution.”

“By detecting these molecules with ALMA, we discovered that there are huge reservoirs of turbulent gas surrounding distant starburst galaxies,” says Bergin, University of Michigan professor of astronomy. “These observations provide new insights into the growth of galaxies and how a galaxy’s environs fuel star formation.”

“Carbon hydride is a special molecule,” says Martin Zwaan, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory who contributed to the study. “It needs a lot of energy to form and is very reactive, which means its lifetime is very short and it can’t be transported far. Carbon hydride, therefore, traces how energy flows in the galaxies and their surroundings.”

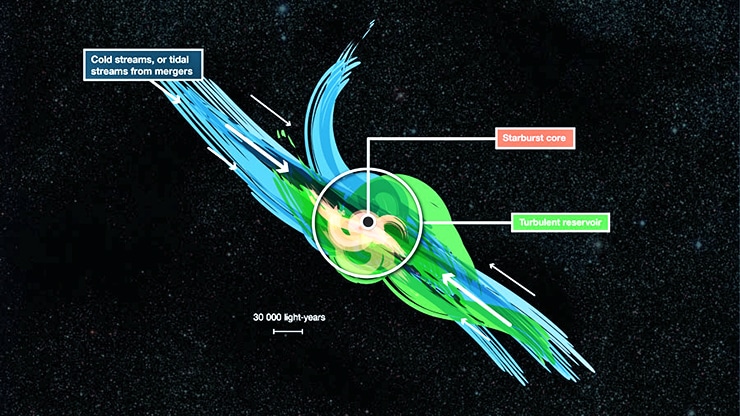

The observed carbon hydride reveals dense shock waves, powered by hot, fast galactic winds originating inside the galaxies’ star-forming regions. These winds flow through a galaxy and push material out of it. Their turbulent motions are such that a galaxy’s gravitational pull can recapture part of that material. This material then gathers into turbulent reservoirs of cool, low-density gas, extending more than 30,000 light-years from the galaxy’s star-forming region.

Did quasars stop galaxies from making tons of stars?

“With carbon hydride, we learn that energy is stored within vast galaxy-sized winds and ends up as turbulent motions in previously unseen reservoirs of cold gas surrounding the galaxy,” says Edith Falgarone of the Ecole Normale Supérieure and Observatoire in Paris.

“Our results challenge the theory of galaxy evolution. By driving turbulence in the reservoirs, these galactic winds extend the starburst phase instead of quenching it,” she says.

The team determined that galactic winds alone could not replenish the newly revealed gaseous reservoirs. The researchers suggest that the mass is provided by galactic mergers or accretion from hidden streams of gas, as predicted by current theory.

“This discovery represents a major step forward in our understanding of how the inflow of material is regulated around the most intense starburst galaxies in the early universe,” says study coauthor Rob Ivison, the European Southern Observatory’s director for science.

“It shows what can be achieved when scientists from a variety of disciplines come together to exploit the capabilities of one of the world’s most powerful telescopes.”

Telescopes spot galaxy bursting with new stars

A study outlining the findings appear in the journal Nature.

Source: University of Michigan