New windows can switch from transparent to opaque and back again in under a minute—a significant improvement over current versions that dim to reduce cooling costs in some buildings.

The “smart” windows consist of conductive glass plates outlined with metal ions that spread out over the surface, blocking light in response to an electrical current.

“We’re excited because dynamic window technology has the potential to optimize the lighting in rooms or vehicles and save about 20 percent in heating and cooling costs,” says Michael McGehee, professor of materials science and engineering at Stanford University and senior author of the study that appears in Joule.

More research is needed to make the surface area of the windows large enough for commercial applications, researchers say. The prototypes used in the study are only about 4 square inches in size. The researchers also want to reduce manufacturing costs to be competitive with dynamic windows already on the market.

Commercially available smart windows are made of materials, such as tungsten oxide, that change color when charged with electricity. But, these materials tend to be expensive, have a blue tint, can take more than 20 minutes to dim, and become less opaque over time.

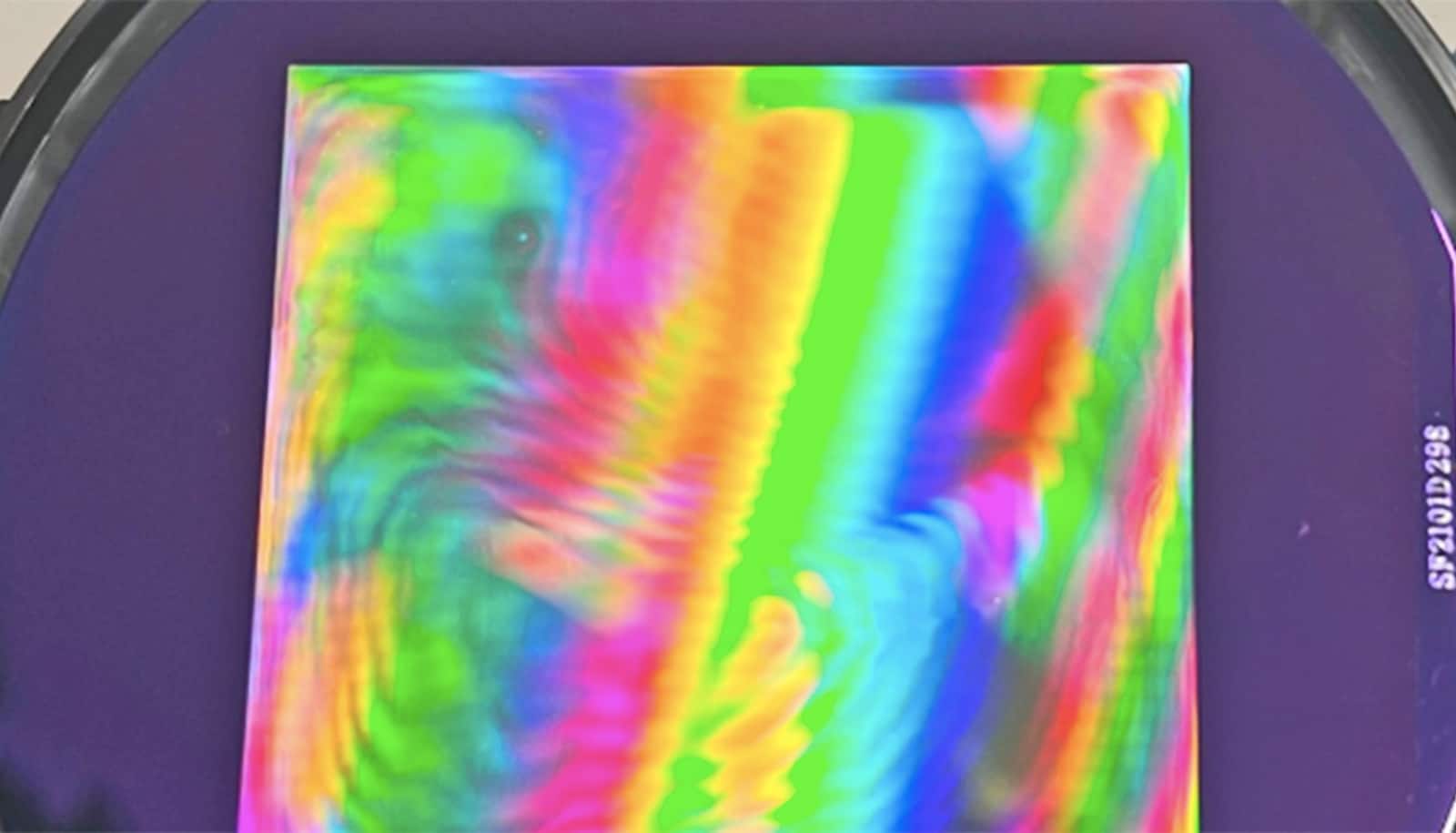

The prototype blocks light through the movement of a copper solution over a sheet of indium tin oxide modified with platinum nanoparticles.

When transparent, the window is clear and allows about 80 percent of surrounding natural light to pass through. When dark, the transmission of light drops to below 5 percent. It only takes about 30 seconds to change from transparent to dark or vice versa.

To test durability, researchers switched the windows on and off more than 5,000 times and saw no degradation in the transmission of light.

“We’ve had a lot of moments where we’ve thought, how is it even possible that we’ve made something that works so well so quickly?” McGehee says. “We didn’t tweak what was out there. We came up with a completely different solution.”

Clear material on windows harvests solar energy

The researchers have filed a patent for the new technology and have entered into discussions with glass manufacturers and other potential partners.

The Precourt Institute for Energy at Stanford, and Stanford Graduate Fellowships in Science & Engineering and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program funded the work.

Source: Stanford University