New research offers a couple of possible explanations for why bisphosphonates—drugs like Fosamax, Boniva, and Reclast—can leave users more vulnerable to a rare but serious form of bone fracture.

These drugs do, however, combat bone loss and fragility fractures in millions of osteoporosis patients for whom a fracture could be debilitating, even life-threatening.

“Because of the changing demographics of our country, the Surgeon General’s office estimates that by the year 2020, half of our population over age 50 will either have or be at risk for fractures from osteoporosis,” says research group leader Eve Donnelly, assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Cornell University.

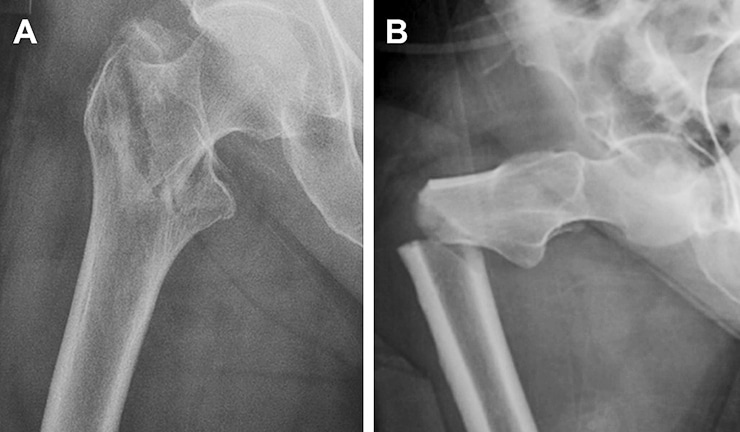

It’s been known for some time that prolonged use of bisphosphonates can put people at risk for atypical femoral fracture (AFF), a break in the shaft of the femur that can occur as a result of little or no trauma. The Donnelly group set out to understand the link between the drugs and AFF.

For this study, published in PNAS, the team examined biopsies of cortical bone—the outer layer—from the shaft of the femur obtained from postmenopausal women during fracture repair surgery. Analysis of bone samples took place at the Cornell Center for Materials Research and with collaborating labs at University of California, Berkeley, and University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf.

Researchers put the participants in five groups, based on fracture type and bisphosphonate use. Some of the women in the study had used bisphosphonates for more than eight years.

“It’s kind of a double-edged sword.”

The testing pointed to a couple of contributing factors: Bisphosphonate-treated women with AFF had bone that was harder and more mineralized than bisphosphonate-treated women with typical osteoporotic fractures. Donnelly says this is due to bisphosphonates’ main function: slowing the resorption (shedding) of old bone, which is typically followed by remodeling, the growth of new bone. In healthy adults, cortical bone is constantly being resurfaced, such that the entire adult skeleton is overhauled every 10 years or so.

But that resurfacing process begins with resorption, and if resorption is slowed by bisphosphonates, the remodeling process is also affected. The result: The existing bone ages and gets brittle over time.

“It’s kind of a double-edged sword,” Donnelly says. “It’s extremely good to prevent bone loss, but the drugs will also slow this natural process, which allows turnover.”

How treating brittle bones prevents gum disease

The other unforeseen side effect to long-term bisphosphonate use involves crack-deflection—the resurfaced bone’s ability to stop a microscopic crack from propagating, which can lead to a break. New layers of bone can act as a “firewall” of sorts, stopping a crack from spreading, but mineralized, older bone loses that function.

“Bone usually has natural variability in mineralization within the tissue, which may help to deflect cracks,” Donnelly says. “As you increase the mineralization, you may tend to lose that natural variation.”

The Food and Drug Administration is now recommending patients use bisphosphonates for three to five years, followed by reassessment of their risk. Donnelly makes it clear that her study is not proposing doing away with bisphosphonate treatment. Studies have estimated the risk of AFF among bisphosphonate users at between one and 10 in 10,000, and have shown the benefit of bisphosphonates continues to far outweigh the risk of AFFs.

One study, published in 2011 on pubmed.gov, estimated that for each reduction of 100 typical hip fractures associated with bisphosphonate use, there was an increase of one AFF.

“That’s one of the cautions I’d like to impart,” Donnelly says. “What we have observed is really the result of long-term treatment, well beyond what the FDA is recommending for these drugs now. Our work explains some of the underlying mechanisms of AFFs and can inform the refinement of dosing schedules for patients at risk of fragility fractures.”

Collaborators on the study come from Weill Cornell Medicine and the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York. Support for the work came from the National Science Foundation and the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Source: Cornell University