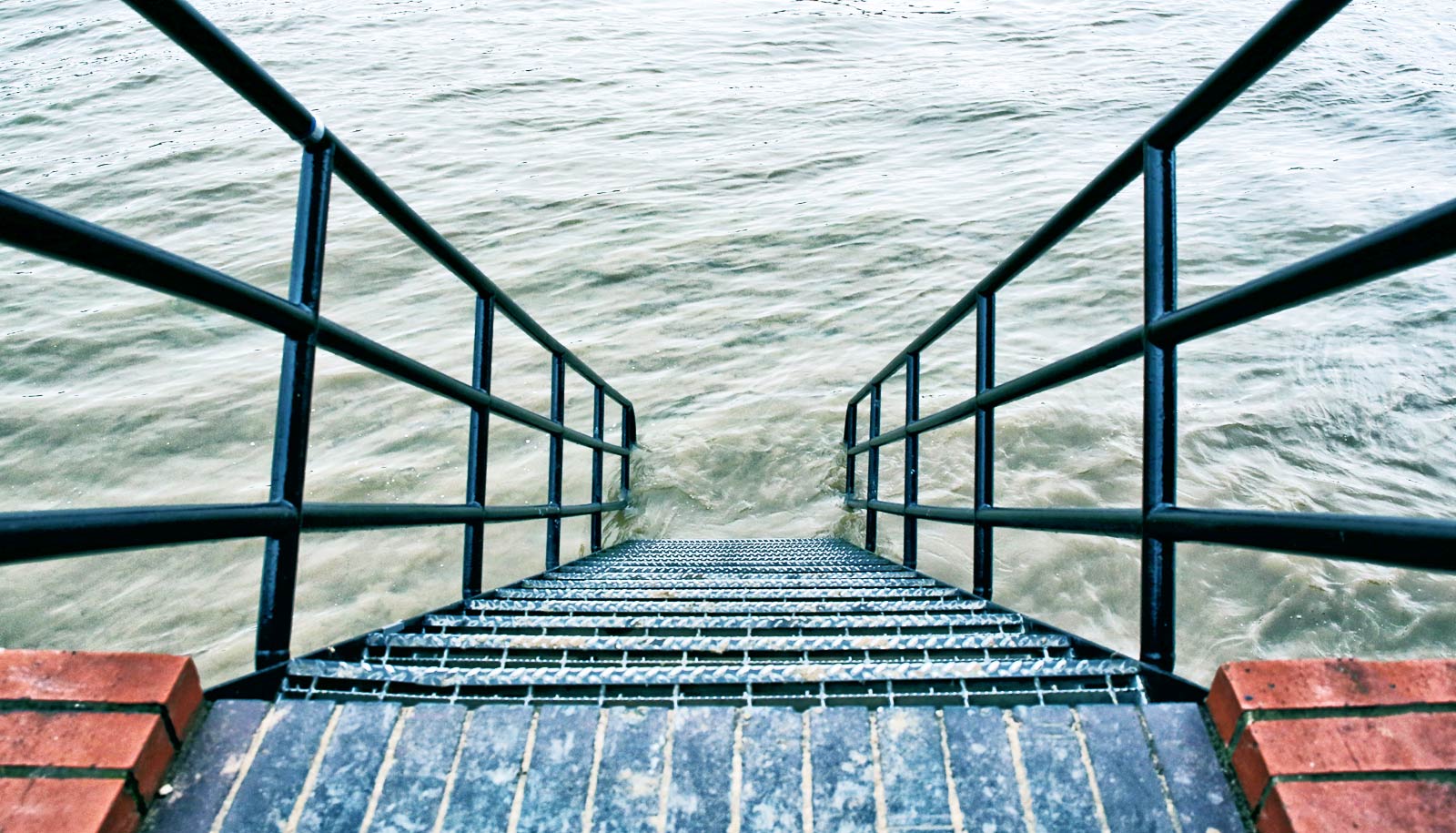

In the year 2100, 2 billion people—about one-fifth of the world’s population—could become refugees due to rising ocean levels. Those who once lived on coastlines will face displacement and resettlement bottlenecks as they seek habitable places inland.

“We’re going to have more people on less land and sooner that we think,” says lead author Charles Geisler, professor emeritus of development sociology at Cornell University.

“The future rise in global mean sea level probably won’t be gradual. Yet few policy makers are taking stock of the significant barriers to entry that coastal climate refugees, like other refugees, will encounter when they migrate to higher ground.

Earth’s escalating population is expected to top 9 billion people by 2050 and climb to 11 billion people by 2100, according to a United Nations report. Feeding that population will require more arable land even as swelling oceans consume fertile coastal zones and river deltas, driving people to seek new places to dwell.

“The colliding forces of human fertility, submerging coastal zones, residential retreat, and impediments to inland resettlement is a huge problem. We offer preliminary estimates of the lands unlikely to support new waves of climate refugees due to the residues of war, exhausted natural resources, declining net primary productivity, desertification, urban sprawl, land concentration, ‘paving the planet’ with roads, and greenhouse gas storage zones offsetting permafrost melt,” Geisler says.

When should climate prompt us to give up land?

The paper in Land Use Policy describes tangible solutions and proactive adaptations in places like Florida and China, which coordinate coastal and interior land-use policies in anticipation of weather-induced population shifts.

Florida has the second-longest coastline in the United States, and its state and local officials have planned for a coastal exodus, Geisler says, in the state’s Comprehensive Planning Act.

Beyond sea level rise, low-elevation coastal zones in many countries face intensifying storm surges that will push sea water further inland. Historically, humans have spent considerable effort reclaiming land from oceans, but now live with the opposite—the oceans reclaiming terrestrial spaces on the planet,” says Geisler.

In their research, Geisler and coauthor Ben Currens, a graduate student at the University of Kentucky, explore a worst-case scenario for the present century.

The authors note that the competition of reduced space that they foresee will induce land-use trade-offs and conflicts. In the United States and elsewhere, this could mean selling off public lands for human settlement.

“The pressure is on us to contain greenhouse gas emissions at present levels,” says Geisler. “It’s the best ‘future proofing’ against climate change, sea level rise and the catastrophic consequences likely to play out on coasts, as well as inland in the future.”

Source: Cornell University