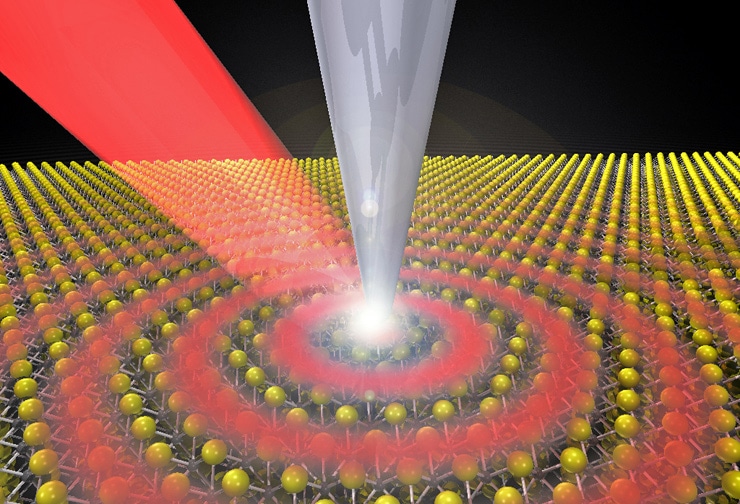

Scientists have made the first real-space images of exciton-polaritons, which are a combination of light and matter.

The nano-image, explains Zhe Fei, shows the waves associated with one of these quasiparticles moving inside a semiconductor.

“These are waves just like water waves,” says Fei, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Iowa State University and an associate of the US Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory. “It’s like dropping a rock on the surface of water and seeing waves. But these waves are exciton-polaritons.”

Exciton-polaritons are a combination of light and matter. Like all quasiparticles, they’re created within a solid and have physical properties such as energy and momentum. In this study, they were launched by shining a laser on the sharp tip of a nano-imaging system aimed at a thin flake of molybdenum diselenide (MoSe2), a layered semiconductor that supports excitons.

Excitons can form when a semiconductor absorbs light. When excitons couple strongly with photons, they create exciton-polaritons.

Fei says past research projects have used spectroscopic studies to record exciton-polaritons as resonance peaks or dips in optical spectra. Until recent years, most studies have only observed the quasiparticles at extremely cold temperatures—down to about -450 degrees Fahrenheit.

But Fei and his research group worked at room temperature with the scanning near-field optical microscope in his campus lab to take nano-optical images of the quasiparticles.

“We are the first to show a picture of these quasiparticles and how they propagate, interfere, and emit,” Fei says.

Scientists are first to detect excitons in metals

The researchers, for example, measured a propagation length of more than 12 microns—12 millionths of a meter—for the exciton-polaritons at room temperature.

Fei says the creation of exciton-polaritons at room temperature and their propagation characteristics are significant for developing future applications for the quasiparticles. One day they could even be used to build nanophotonic circuits to replace electronic circuits for nanoscale energy or information transfer.

Fei says nanophotonic circuits with their large bandwidth could be up to 1 million times faster than current electrical circuits.

The researchers also learned that by changing the thickness of the MoSe2 semiconductor, they could manipulate the properties of the exciton-polaritons.

“We need to explore further the physics of exciton-polaritons and how these quasiparticles can be manipulated,” says Fei. That could lead to new devices such as polariton transistors, he says. And that could one day lead to breakthroughs in photonic and quantum technologies.

Fei’s team reports its findings in Nature Photonics. Coauthors are from Iowa State; the University of Washington; Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the University of Tennessee; and the University of Washington.

Iowa State and the Ames Laboratory contributed funding to launch Fei’s research program. The W.M. Keck Foundation of Los Angeles also partially supported the nano-optical imaging for the project.

Source: Iowa State University