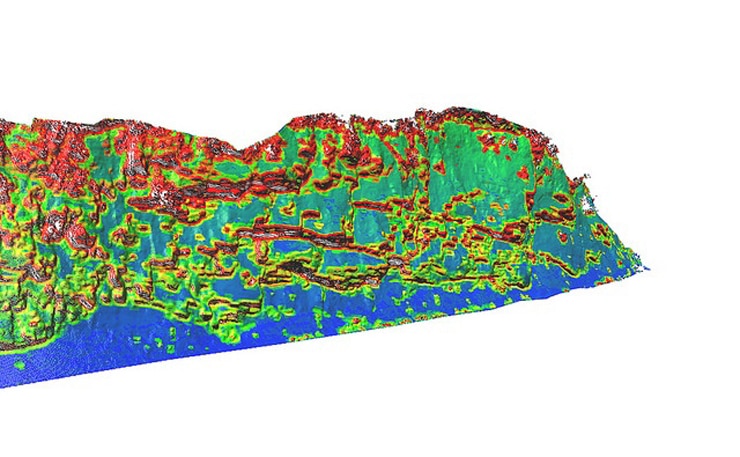

A new, automated technology analyzes the potential for rockfalls from cliffs onto roads and areas below. The system could speed and improve risk evaluation, help protect public safety, and ultimately save money and lives.

The system, based on the powerful abilities of light detection and ranging, or LIDAR, technology, could expedite and add precision to what’s now a somewhat subjective, time-consuming process to determine just how dangerous a cliff is to the people, vehicles, roads, or structures below it.

“Transportation agencies and infrastructure providers are increasingly seeking ways to improve the reliability and safety of their systems, while at the same time reducing costs,” says Joe Wartman, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington, and corresponding author of the study in Engineering Geology.

“As a low-cost, high-resolution landslide hazard assessment system, our rockfall activity index methodology makes a significant step toward improving both protection and efficiency.”

The new approach could replace the need to personally analyze small portions of a cliff at a time, looking for cracks and hazards, with analysts at times needing to rappel down to assess risks. LIDAR analysis can map large areas in a short period, and allow data to be analyzed by a computer.

“Rockfalls are a huge road maintenance issue,” says coauthor Michael Olsen, associate professor of geomatics at Oregon State University.

“Pacific Northwest and Alaskan highways, in particular, are facing serious concerns for these hazards. A lot of our highways in mountainous regions were built in the 1950s and 60s, and the cliffs above them have been facing decades of erosion that in many places cause at least small rockfalls almost daily. At the same time traffic is getting heavier, along with increasing danger to the public and even people who monitor the problem.”

Landslides travel a long way when rocks flow like fluid

Based on some examples in southern Alaska, the study shows that the new system could evaluate rockfalls in ways that very closely match the dangers actually experienced. It produces data on the “energy release” to be expected from a given cliff, per year, that can then be used to identify the cliffs and roads at highest risk and prioritize available mitigation budgets to most cost-effectively protect public safety.

Rock slope maintenance and mitigation cost tens of millions of dollars each year in the United States.

“This should improve and speed assessments, reduce the risks to people doing them, and hopefully identify the most serious problems before we have a catastrophic failure,” Olsen says.

The technology is now complete and ready for use, although the researchers are continuing to develop its potential, possibly with the use of flying drones to expand its data.

Additional researchers from the University of Washington and the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, are coauthors of the study. The Pacific Northwest Transportation Consortium, the National Science Foundation, and the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities supported the work.

Source: University of Washington