New research finds human-shark interactions can take place without long-term effects on the sharks.

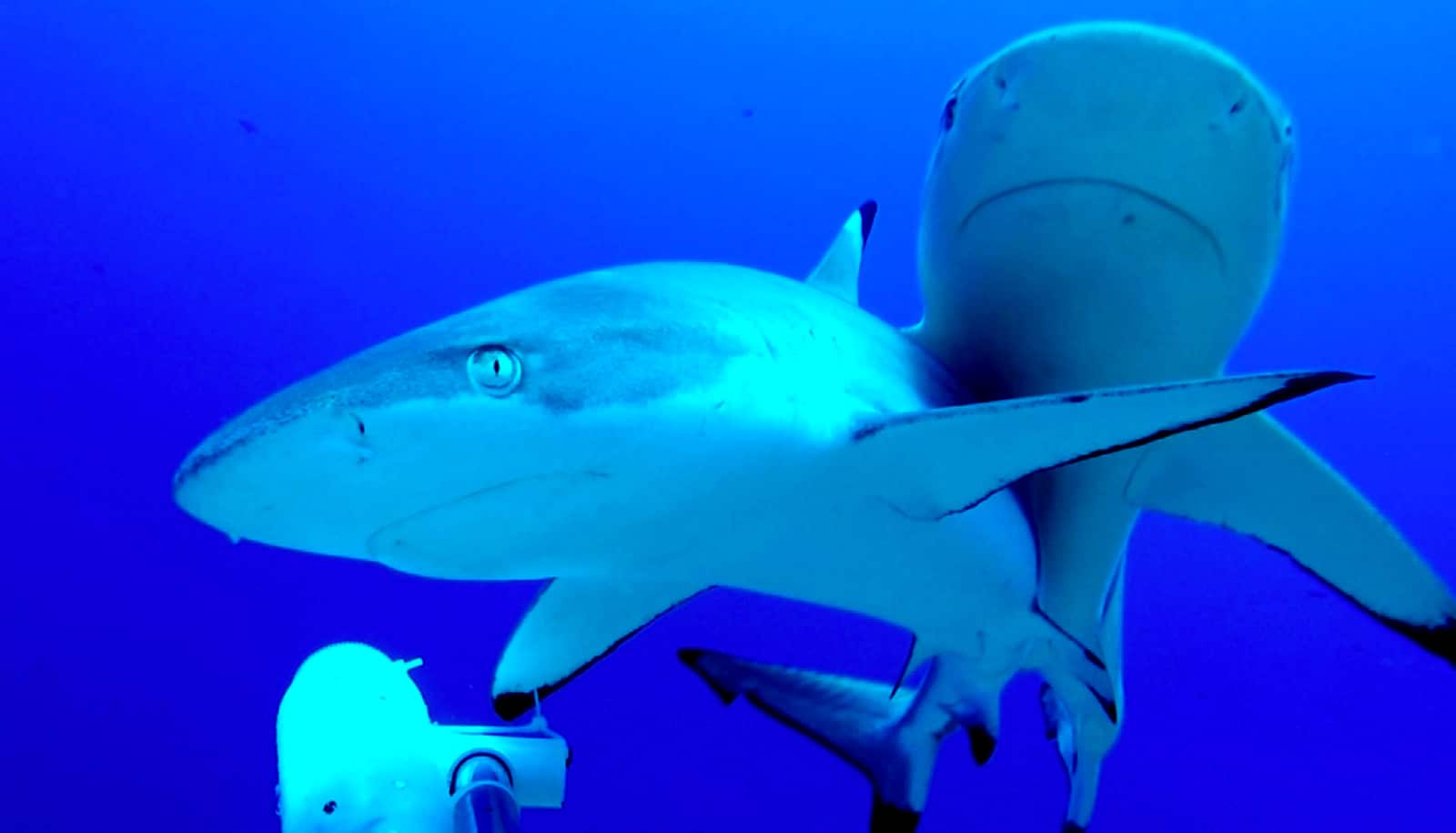

A multimillion-dollar global industry exists in response to scuba divers’ interest in getting face time with the ocean predators. Options include cage diving with white sharks in South Africa and Guadeloupe Island; shark feeding in the Bahamas, Mexico, or Fiji; and diving with huge schools of hammerheads in Cocos Island and Galapagos.

But as most scuba divers know—and previous studies have shown—sharks more commonly swim away from people than toward them. Does that avoidance behavior persist after the divers leave? Do sharks steer clear of sites that are frequented by divers?

“Unfortunately, human impacts on shark populations are ubiquitous on our planet,” says lead author Darcy Bradley, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. “That makes it difficult to separate shark behavioral changes due to scuba diving from behavioral changes caused by other human activities like fishing.”

The researchers went to Palmyra, a remote atoll in the central Pacific Ocean, where shark populations are healthy, fishing is not allowed, and divers rarely enter the majority of its near pristine underwater world. However, Palmyra is home to a small scientific research station, where researchers dive in a handful of locations. This made the atoll an ideal site for studying whether and how shark abundance and behavior differ between locations where diving is more common and those where it is not.

As reported in the Marine Ecology Progress Series, the researchers used baited remote underwater video systems—cameras lowered to the ocean floor with a small amount of bait—to survey sharks and other predators from the surrounding reef.

Tourists see fewer wolves when hunters get close

“After reviewing 80 hours of underwater footage taken from video surveys conducted in 2015—14 years after Palmyra was established as a wildlife refuge and scientific diving activities began—we found that shark abundance and shark behavior were the same at sites with and without a long history of scuba diving,” says coauthor Jennifer Caselle, a research biologist at UC Santa Barbara’s Marine Science Institute.

“Our results suggest that humans can interact with reef sharks without long-term behavioral impacts,” Bradley says. “That’s good news. It means that well-regulated shark diving tourism doesn’t necessarily undermine shark conservation goals.”

Researchers from Florida International University also contributed to the work.

Source: UC Santa Barbara